1985: Where R&B and CCM Meet

Despite its larger reputation for being a pop-centric genre, Russ Taff, Jessy Dixon and Howard McCrary dared to bring an R&B edge to the CCM market once upon a time.

The presence of Black artists and the sound of Black music in contemporary Christian music (CCM) has always been a tenuous thing. While Andraé Crouch did significant work during the Jesus Movement (in the late 60s and early 70s) to foster community and make inroads for other Black artists in this burgeoning new form of music, the reality was that by the end of the 70s, it was still a challenge for Black artists or artists who bore the influence of Black music to find an interested or receptive audience. I’ve written in previous entries about white artists like Stephanie Boosahda and Reba Rambo who were heavily imprinted by Black music and there were a number of Black artists like Bob Bailey, Lanier Ferguson and Bili Thedford all on their own singular paths in CCM, but their forward progression was hindered by the limitations and prejudices of the market they were breaking into as well as the lack of avenues for contemporary gospel to be featured within the larger spectrum of Black gospel music. When artists like Bonnie Bramlett and Maria Muldaur became Christians in the early 80s, they thought CCM would be the space in which they could record music that reflected their faith, but, despite their best efforts, their blues-oriented sound was blantanly ignored by Christian radio programmers.

Christian radio was historically and famously not receptive to these sounds out of deference to their listeners, many of whom regurgitated racist talking points that they’d heard from their pastors about the origins of the music. But Christian radio simply mirrored the same exclusion that Black artists faced in pop music. But the 80s were reflecting a slight shift for R&B artists. Not only were R&B artists finding placement on the pop charts, but white pop artists were always making music that was embraced by Black radio. When CCM artist Kathy Troccoli began working on her sophomore album, Heart & Soul, in 1984, she told CCM magazine that she sought out R&B material for the project, but “Heart & Soul was a little bit frustrating for me because a lot of people weren’t writing R&B and it was like ‘Let’s write these songs for K.T. She wants an ‘All Night Long’ song.’ Michael (W.) Smith comes up with ‘Holy, Holy’ and that kind of thing.” As I noted in the feature, there were certainly artists writing the kinds of songs she was looking for—but such was the divide in that era.

While Troccoli was crafting her spectacular Heart & Soul, Russ Taff was crafting his own sophomore album, Medals, that would capsulize his distinct brand of R&B-infused power pop, resulting in the most successful album by a male artist in 1985. While his debut album, the Grammy-winning Walls of Glass, had been successful, Taff saw it, in his own words, as an attempt to “hit right for the middle, and it was a bit frustrating.” With Medals, Taff took control, co-producing the album himself with engineer/producer Jack Joseph Puig who was involved in CCM’s most cutting edge albums as well as albums like Kenny Loggins’ Vox Humana, Earth, Wind & Fire’s Maurice White’s self-titled solo debut and Patti Austin’s Gettin’ Away with Murder.

Medals was, indeed, a shift in direction. If Walls of Glass rolled steadily on the ocean, Medals was a thunderstorm. Supported by LA’s finest studio musicians including James Newton Howard (Irene Cara, Chaka Khan, Brenda Russell), Seawind’s Larry Williams (Michael Jackson, The Brothers Johnson, Jeffrey Osborne), Paul Jackson Jr. (Donna Summer, The Pointer Sisters, Deniece Williams), and Michael Landau (Laura Branigan, Sheena Easton, Rod Stewart), Medals delivered ten stellar compositions that, with Russ’ voice on top, were, as one critic wrote, “sound better than the average pop music recorded and released….[using] state-of-the-art production and tasty musical work to support Taff’s soulful vocals.” Singer/songwriter John Hiatt praised Taff as “one of the finest white soul singers around,” and Billboard’s Christian music critic declared him “the single most electrifying voice in music today.”

Medals sold a staggering 350,000 units—only trailing behind Amy Grant and Sandi Patty on the CCM album sales chart. It out-performed Grant’s Unguarded on the radio side, scoring four Top Ten singles on the national Christian radio airplay chart, with “Silent Love” taking the #1 position in the summer of 1985. The singles—all ballads—most reflect the timidity of Christian radio, leaving the album’s most groove-oriented and hook-laden songs like Roby Duke’s “I’ve Come Too Far” (featuring Táta Vega and Carmen Twillie on background vocals) and “How Much It Hurts” to linger as album cuts. While “Vision” and “Rock Solid” would have been no-brainers as singles in the mainstream market, they only received play on youth-oriented programming for the stations who even had such a thing. Taff lamented to the Poughkeepsie Journal as he promoted Medals, “There are very few real progressive contemporary Christian radio stations.”

Despite promises to promote Medals to the general market, A&M Records put all of its resources into Grant’s Unguarded and Medals got lost in the shuffle, never receiving the mainstream boost it was certainly worthy of. While the album was far more specific, spiritually-speaking, than Grant’s Unguarded was, it wasn’t dogmatic—it was human. One review noted its distinction from the militaristic fundamentalism spouted by the likes of Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, and the ways that Medals “challenges the popular right-wing leanings of many denominations.” (Click here to read my personal account of what Medals to me and hear my interview with Russ’ co-writer and wife, Tori, about the making of the album)

Listen to Medals here.

But, as I’ve written here many times, nothing is a monolith. While the more R&B-oriented tunes on Medals weren’t pushed as singles, that doesn’t mean that there weren’t a handful of artists who managed to expand the palette of the CCM market.

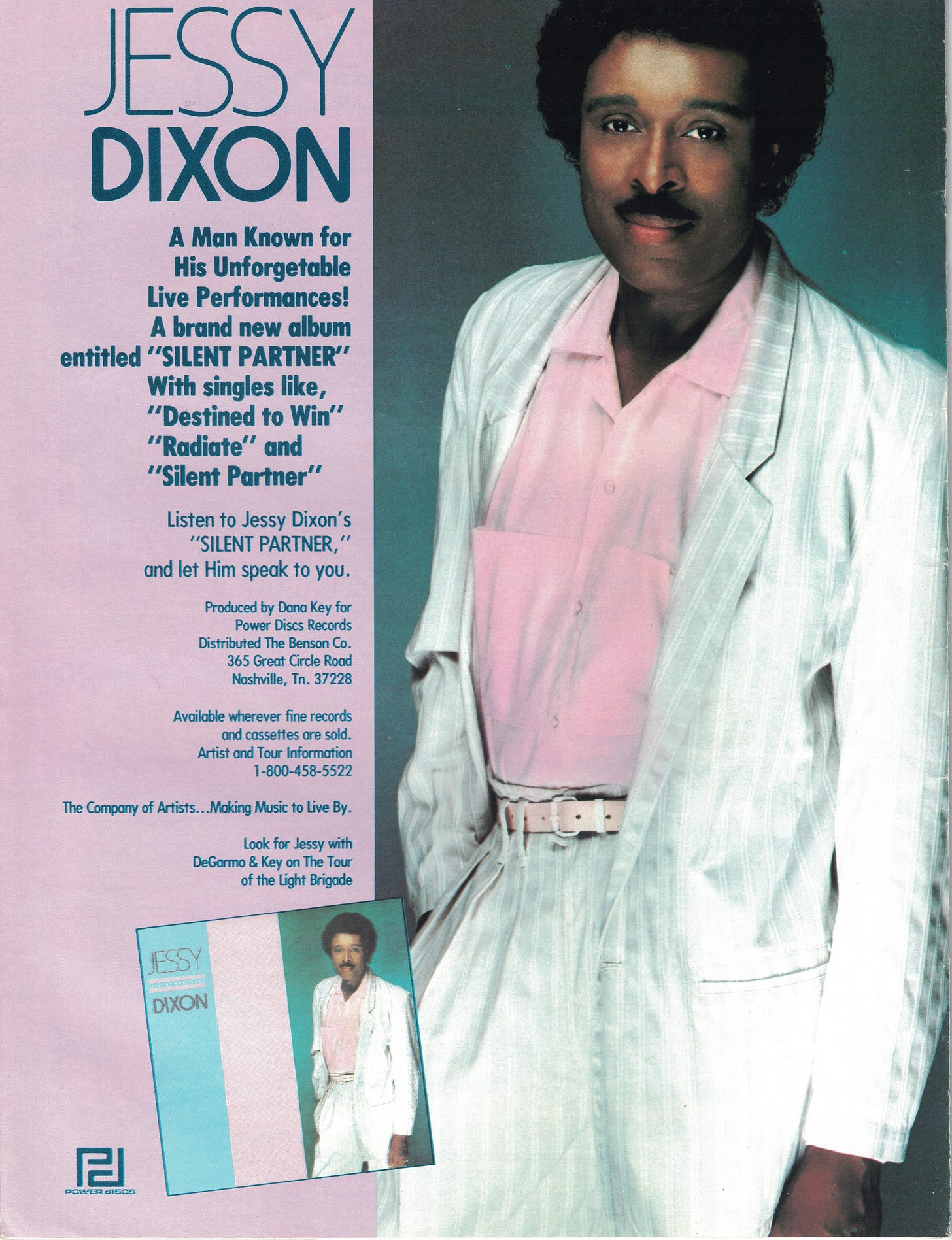

Jessy Dixon already had more than two decades under his belt as a gospel artist by 1985. As a member of the Gospel Chimes (some say he or James Cleveland actually founded the group), organist for the Chicago Community Choir and, beginning in 1964, a solo recording artist for Savoy Records, Dixon had been innovating a contemporary gospel sound from the beginning of his career (One can’t forget that his composition “God Is Standing By” became a standard after being recorded by Walter Hawkins & The Love Center Choir on the seminal Love Alive in 1975). In the 1972, he and his group began touring with Paul Simon, bringing the gospel sound to audiences around the world. A concert with Andraé Crouch & The Disciples and Danniebelle Hall in 1977 began conversations with Light Records, which introduced him to the world of contemporary Christian music.

While Dixon’s success in secular music as a songwriter and backing vocalist brought him press in the CCM market, it didn’t bring airplay. His three albums were polished, well-produced efforts (two of which were produced by Dixon himself) that made no attempts to hide Dixon’s fiery gospel leanings, but rather utilize them as flourishes for his distinct brand of soulful, adult contemporary music. When he signed with DeGarmo and Key’s Power Discs imprint in 1983 (distributed by the Benson Company), he scored an immediate hit with the album’s title track, “Sanctuary,” but the album’s broader praise and worship-oriented bent disoriented his audience. He told CCM, “The age of my audience has always ranged from the teens to the forties and they’ve always been with me. Sanctuary was too slow for them. They were just excited about Jesus and weren’t into the deep theological things that I was saying on that album.”

Dixon paid attention and opted to work with DeGarmo and Key’s Dana Key as producer of the album that would become Silent Partner, arguably Dixon’s most well-crafted, commercially ambitious release. Determined to make an album that was viable in the increasingly youth-oriented market, he opted to not contribute to the project as a songwriter. “I think that’s the responsibility of DeGarmo and Key, Amy Grant, myself…to make good music and to use the best arrangers so that the record will sound as commercial as possible and yet be as strong as possible lyrically. The kids will do the rest. That’s a witnessing tool and I’m excited about being a part of it.”

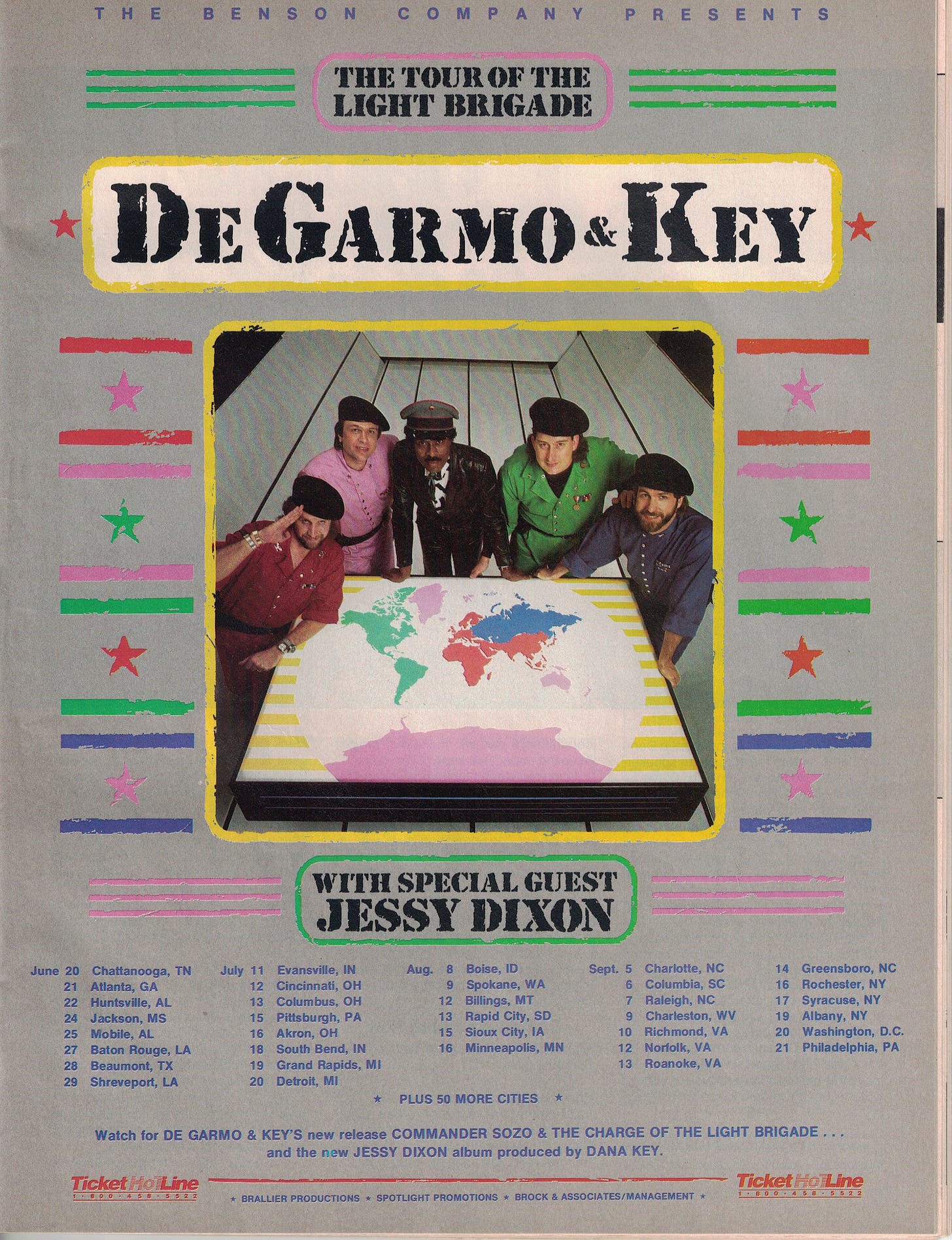

DeGarmo and Key’s foundation in blues, rock and soul always bled through in their own recordings and their collaboration with Dixon was an even greater amplification of those influences and a perfect channel through which their songs could be elevated. Like Medals, Silent Partner erupts from the first note of the Huey Lewis-influenced “Radiate,” which wears the influence of Lewis’ “The Heart of Rock and Roll” unabashedly.

To fully appreciate Silent Partner, one has to listen to D&K’s release, Commander Sozo & the Charge of the Light Brigade, released in tandem with Silent Partner. Arguably, this could be defined as D&K’s hot streak with these albums following their stellar 1984 release, Communication. Sozo and Silent Partner are certainly in conversation with each other. While D&K used Sozo to provoke Christians out of perceived apathy, Silent Partner was a tool of encouragement, affirmation and invitation to those in and outside of the church.

The album’s strongest material comes from the duo’s pen. “Spiritual Solution,” another D&K composition that might have fit on their own Sozo album, has the sheen of a Robert Palmer track and the musical bells and whistles that invoke the best of 80s nostalgia. The album’s title track is reminiscent of something one might have heard on one of the Miami Vice soundtrack albums with Dixon crooning against a track that brings the Mary Jane Girls and Cherelle to mind.

Not unlike Russ Taff’s “Not Gonna Bow,” “I Won’t Bow Down” (written by Terri McFadden, composer of NYCC’s “Keep a Light in My Window”) could be heard as a refusal to bend to peer pressure “in the world” or in the church. Sonically, the song blends so perfectly between the D&K compositions that it sounds like it’s one of their own. On his prior releases, Dixon shone on the ballads, but on Silent Partner, the ballads, all written by external composers, feel disconnected from the rest of this well-oiled machine.

The album’s centerpiece is “Destined to Win,” a duet with DeGarmo and Key, and a collaboration with their band. It’s the album’s most gospel-infused moment on which Dixon lets loose, transforming a song that might otherwise have just come off as nothing less than a jingle into an authentic, motivational anthem.

While the CCM market received Silent Partner with open arms—both the title track and “Destined to Win” were successful singles—Dixon’s gospel audience turned even further away than they had with Sanctuary. He told the Chicago Tribune in 1987 that he’d been labelled a sell-out by his peers in gospel music. “It hurts, it really hurts, when I hear that some people think I’ve sold out because I certainly never sat down and decided that I no longer wanted to sing for the Black gospel audience. It’s just that the type of music I feel comfortable doing is more universal in its appeal. It’s like Lionel Richie and the Pointer Sisters. They appeal mostly to white audiences, too. I’m just doing it in gospel.”

Listen to Silent Partner here.

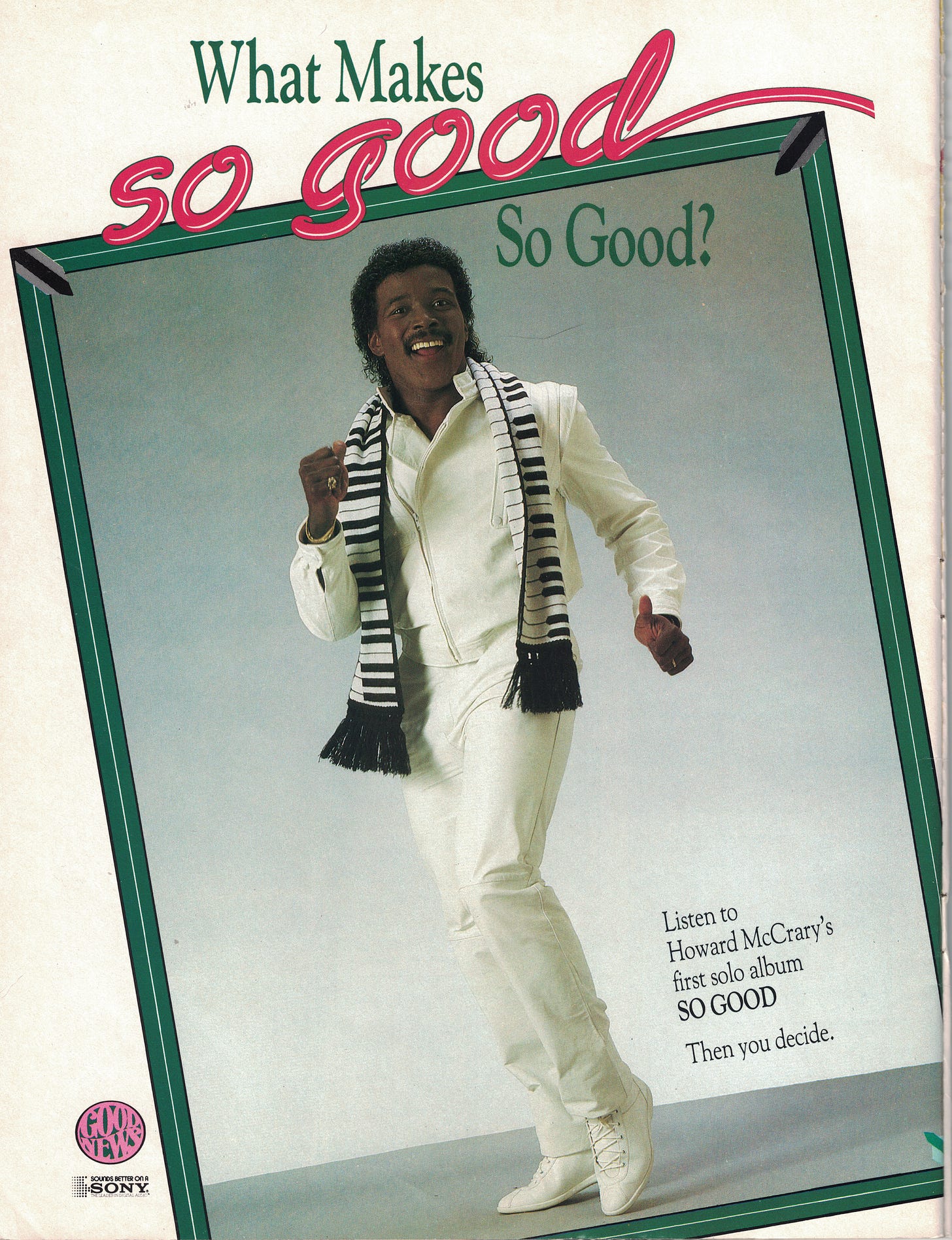

In similar fashion, Howard McCrary released his solo debut, So Good, that year as well. McCrary was not a household name, but should have been. By 1985, he was a veteran who had been involved with contemporary Christian music almost from the very beginning. He and his family recorded their Light Records debut in 1972 and were soon recording background vocals for artists like Barry McGuire and Pat Boone, in addition to cultivating his own cabaret act in Los Angeles, while also maintaining duties at a number of Los Angeles’ churches including Rev. Benjamin Crouch’s Christ Memorial Church of God in Christ.

Branded as “The Stevie Wonder of Gospel,” McCrary’s songwriting and arranging skills began to open other doors and he became the musical director at Jim and Tammy Bakker’s Heritage USA. From that springboard, he began writing, producing and arranging for artists like Bob Bailey, Larnelle Harris, Andraé Crouch, Howard and Vestal Goodman, Maria Muldaur and many others. It wasn’t until 1985, however, that he recorded his debut album as a solo artist, the rightfully titled So Good.

What So Good has in common with Medals and Silent Partner is a clear understanding of pop accessibility. Utilizing many of the same session players who supported Medals, the album plays like ear candy, moving from one memorable, singable hook to another. McCrary’s voice with it’s Motown-ish sweetness is on the opposite end of the spectrum from Taff and Dixon who both reek of a more gutteral gospel influence. Interestingly, the handsome McCrary, the most ideal to fit in CCM’s confines, didn’t reach the heights of either artist.

Where McCrary’s album differs from both Medals and Silent Partner is that it doesn’t seem particularly interested in having the commercial possibility in the mainstream that Taff, Dixon and other artists from this era were vying for. McCrary’s focus in this moment of this career was to write and produce music largely intended to edify and educate Christians. Songs like “Yahweh,” “Sold Out,” and “Greater is He” all utilize insider language that might have been confounding and, for some, laughable outside of Church Culture.

“Hold Tight,” on the other hand, a song about suicide, might have had the most reach beyond the walls of the church. McCrary told CCM magazine, “I tried to commit suicide—twice. The first time, I tried an overdose of pills. The second time, I tried to hang myself. I could not bear up under all the peer pressure. I took life too seriously. I worried all the time. All of that was misdirected energy. Each of us has to recognize his limitations, that we are not meant to do everything. Parents especially need to realize this so they don’t push their kids against brick walls that are impossible to climb. I am thankful that God is far more forgiving than people are—than I am.”

It’s important to recognize, however, that what I call “insider music” was still very much en vogue on Christian radio…and because that was the case, it’s fair to say that So Good got slighted. “Mansions of Glory,” “This Jesus” and “My Incorruptible Crown” foretell the kinds of songs that 4Him, Ray Boltz and Phillips, Craigs and Dean would have massive hits with in the decade ahead—but McCrary’s album, despite favorable reviews, much like Bob Bailey’s 1983 album I’m Walkin’, was virtually ignored. If it weren’t for the fact that it received a Grammy nomination in 1986 in the Male Soul Gospel category alongside Marvin Winans, Marvin Yancy, Philip Nicholas and Douglas Miller, So Good might otherwise be completely forgotten by anyone who isn’t a McCrary fan or CCM aficionado.

Without artists like these three (and the others mentioned throughout the article) willing to push the boundaries within CCM, the success of R&B-tinged acts like BeBe and CeCe Winans, Tim Miner, Helen Baylor and Crystal Lewis may not have happened. That is not to say that the walls were knocked down though. For every success, there were talented artists making viable music that could not get a foot in the door.

Merch Available Now!

God’s Music is My Life shirts (short and long sleeve), hoodies, caps, mugs and stickers are available now! SHOP HERE!

Church of the Good Groove

The January 2025 edition of my Church of the Good Groove playlist is now up! Just click here to listen!

In recent months, I've been digging up my cassette mixes from the 1980s and have been amazed at how close to secular music in quality some of these artists were, such as Russ Taff and Amy Grant. They made some really good stuff. As for r&b, I'd heard of Jessy Dixon, and I think I heard his music back in the '80s but it didn't do anything for me. I've never heard of Howard McCrary.

The big r&b crossover for me was Tramaine Hawkins. To this day, I love listening to her 12" singles from the 1986 album The Search Is Over. "In The Morning" is the hottest-sounding mix, and the song is incredibly energizing. You can't find sound quality this good today (at least not easily). Even the album's sound quality was top notch. I also love the 12" singles "Fall Down" and "Child Of The King." I don't like gospel music, but these 12" singles were r&b/dance music that stayed enough away from a gospel sound that I could relate to them. Well, "In The Morning" gets gospel-y at the end, but the way it builds up to that point, I don't even care by the time I get there -- those "Hallelujahs" are incredible!

Her subsequent album Freedom (1987) was also r&b and was good, but it was a step down from the energy and sound quality of The Search Is Over. I have 12" singles from the Freedom album also.

I am loving hearing from Russ Taff and Jessy Dixon--the latter is new to me. I am so moved when a singer gets inside the Gospel stories.