Song of the Soul: Honeytree & Cris Williamson

A detailed analysis of Honeytree's 'Evergreen' and Williamson's 'Changer,' career-defining albums from the Jesus Movement and Women's Movement, respectively, celebrating their 50th anniversaries.

Two weeks ago, I wrote about my work with Reba Rambo on a series of reissues that re-evaluate her contribution to the world of contemporary Christian music. I noted in that article that Reba was part of a robust, innovative group of women in the sixties and seventies who were doing revolutionary work in a field that was unaccustomed to and, largely, uncomfortable with women having any kind of platformed voice. This week, I’ll look at one of the era’s most embraced women. Nancy Henigbaum—introduced to the public simply as Honeytree—became a symbolic figure of the Jesus Movement of the seventies and songs like “Clean Before My Lord” and her cover of Larry Norman’s “I Am A Servant” were staples of the era. The latter was from her 1975 release, Evergreen, arguably the most definitive album of her career.

The Women’s Movement was happening in tandem with the Jesus Movement. While, on the surface, these two moments had little relationship, they share a commonality: music was a powerful vehicle through which their message was advanced. The idea of Women’s Music—music made by, for, and about women, is credited to Meg Christian who, with a collective of women, began Olivia Records. Changer has been defined by critics as seminal, praised decades later by National Public Radio’s Ann Powers as “the cornerstone of the feminist ‘women’s music’ movement.’”

Both albums turn fifty this year and this week I dig beneath the surface of two seemingly disparate artists who are symbols of movements that don’t appear to have much in common but share more similarities than are immediately apparent.

Honeytree was an unlikely candidate for a career in contemporary Christian music. Born into an Episcopalian family with a deep love for classical music as a result of their father, a symphony conductor, she began playing an instrument at an early age. While the Episcopalian church relayed a message of personal responsibility, “I didn’t really hear a message of urging me to receive the Lord as my Savior or anything,” she explained in our 2016 interview. During the folk revival of the sixties, she mastered her guitar and became enamored with the music of Bob Dylan, Judy Collins, Joni Mitchell and the genre-converging Laura Nyro.

Her introduction to any kind of con-temporized Christian music came by way of Edwin Hawkins’ crossover hit, “Oh Happy Day,” which hit the #4 position on Billboard’s Hot 100 in 1969 while she was a senior in high school. “I loved it so much that I went out and bought the album,” she says. “I loved the intensity of the way they sang with all their hearts. I was listening to that quite a bit. The Lord used that song, you know? He opened up that door for that song to get out there.”

Indeed, for Honeytree the song became a gateway to a different relationship with Christianity. While visiting her sister in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, she had her first encounter with “Jesus People” and attended a service at Calvary Temple with them. She told me, “I was very, very moved by the worship time. I had never heard people singing choruses in church and just repeating them and not looking at a hymn book, but knowing them and just lifting their hands. They were so into it and I just couldn’t understand. I wasn’t a part of it and that was very obvious to me. The next day, when I went back to ask questions and talk about it…that was the day I got saved.”

She spent her senior year going back and forth between Iowa and Indiana, immersing herself in Calvary Temple’s community, getting in on the ground floor of The Adam’s Apple, a coffeehouse they were opening. After spending the summer as a camp counselor, she moved in the fall of 1970 and began writing songs out of her experience. The ministry was a gathering place for a variety of local and national artists, musical, literary, and visual, who were innovating new ways to communicate their faith. “We were the midwest stop for anybody that was on the road that was singing Jesus Music. So we had Larry Norman, Randy Stonehill, and 2nd Chapter of Acts, Randy Matthews….it was absolutely phenomenal.”

When Calvary Temple’s pastor’s son heard Honeytree’s music, he felt she should record and arranged her first sessions for a custom album produced by Joe Moscheo (then a member of the Imperials) and Paul Craig Paino. The enterprising Paino took the album to the Christian Bookseller’s Association and, along with Andraé Crouch, began passing Honeytree’s album out to the attendees who were largely retailers and executives. When radio personality Paul Baker asked Crouch for an interview, he agreed on the condition that Baker play Honeytree’s album on the show. Baker subsequently urged Billy Ray Hearn, who was heading up Word Records’ Jesus Music division, Myrrh Records, to listen to the album. Hearn quickly signed Honeytree to Myrrh, purchased the rights to the custom album, and began distributing it to the Christian market.

Word Records’ dimpled darling Evie subsequently recorded “Clean Before My Lord” and it became a hit, introducing Honeytree to the masses. For traditionalists, she was indeed edgy (people questioned her usage of the bassa nova rhythm on ‘Clean’), but her unobtrusive appearance and mellow sound were a bridge to older listeners completely put off by the electrified rock of Larry Norman and Petra.

Her sincerity and full-hearted belief in the Movement likely shielded her from being deeply affected by some of the sexism that existed within Christian culture.

While acknowledging “there was probably some macho-ism that I lived with…I didn’t really even notice. I just was so in love with Jesus. Some people were offended that I was a woman who was up in front of people—and there were men [who believed] you know, women are supposed to be silent in the church. I never got into trying to validate women in the ministry. I was too busy doing it.”

1974’s The Way I Feel was a creative leap on musical and lyrical plains, revealing a progression from being a folk-centered artist who wrote exclusively worship-centered lyrics to a broader, folk-rock sound with more introspective themes that addressed her insecurities and struggles for self-acceptance.

Somehow let me see who I am

I see who I am not

See what I haven’t got

But who am I?

Somehow let me say how I feel

I think you’d take my hand

If you could understand

The way I feel

I’m shy, but please

Don’t take no for an answer

‘cause I’ve got things

to share with you

There’s a person deep in my soul

I think I see her now

She wants to show you how it feels

To be…Honeytree (from ‘Honeytree’ from The Way I Feel)

1975’s Evergreen built up on the larger sound that The Way I Feel had introduced, pairing Honeytree with some of Nashville’s most seasoned arrangers and players like Bergen White, future super-producer Tony Brown, Ron Oates, and Jerry Carrigan. Assisting with the production and providing guitar mastery was Phil Keaggy, an artist whose debut solo album, What a Day, was released in 1973. The resultant release is the most consistent and buoyant album of Honeytree’s career.

Evergreen bears a resemblance to the work of singer-songwriters who began their trek from the underground to the mainstream. The production on Phil Keaggy’s composition, “Lovely Jesus (Here I Am)” echoes the kind of chord structure and string arrangement folk-pop crossover artist Carly Simon had employed on 1974’s “Haven’t Got Time for the Pain,” while “Searchlight,” perhaps her most driving recording, shares a commonality with Barry Manilow’s “New York City Rhythm,” which would be released around the same time as this album.

What the album does most effectively is give Honeytree weight as an artist. As she’d begun to do with The Way I Feel, she shifted from the worshipful choruses and began to share her personality and thoughts with her listeners. While she kept her faith central, the songs reflect a well-rounded woman who was also occasionally melancholy and uncertain, but also self-assured and deeply humorous. Her humor is captured on the ode to old-time-rock and roll, “Rattle Me, Shake Me,” which captures both the head-in-the-clouds whimsy of the Jesus Movement, something that, decades later, plays to younger ears as cheesy, but completely understandable to anyone who was there. The song became a signature song of her career and remains a staple of her live performances.

Honeytree wisely nods to three women from the Bible in two compositions, “Ruth” and “Mary and Martha.” The two songs serve as a prelude to Larry Norman’s “I Am a Servant” (a song he would record himself on 1976’s In Another Land). The three songs, retrospectively, converge to make a passively feminist statement, as if to say to any who might chaff at the presence of women with a microphone, “We’ve always been here.”

Evergreen marked the end of Honeytree’s collaboration with Billy Ray Hearn who left Myrrh upon its release to found Sparrow Records. She stayed at Myrrh, a decision she says was “tragic. I never really fit as well with the people that I ended up working with after he was gone.” Her subsequent albums on Myrrh, the gorgeous The Melodies In Me and Maranatha Marathon were out of step with where the Christian music industry was heading as the eighties dawned, a period she describes as a “dark period…where I felt that I wasn’t wanted. I was struggling with the end of the Jesus Movement and I didn’t really feel in the middle of everything anymore. I didn’t really relate to this new sort of young people that were, you know, Amy Grant and Michael W. Smith fans.”

She wouldn’t release another commercial album until 1985’s Single Heart. She has continued to work in the local church and in the missions field. She told The Weirton Daily Times in 2015, “My feelings are complicated because I am totally unknown to most people in [Contemporary Christian Music], so, of course, I feel odd about that. It’s like a Pharaoh has arisen who doesn’t remember Joseph. My theory is that a generation in the music business only lasts seven years, and then you’ve got a whole new youth audience to cater to.”

But the music business isn’t the only thing that has changed since Evergreen. The ‘come one, come all’ tenor of the Jesus Movement has been exchanged for a polarizing and excluding political agenda. At the close of our 2016 interview, she said,

“The other thing that distresses me is that Christianity and the Republican party are supposed to be synonymous. That is really tragic and has turned off a lot of people from the gospel who just cannot relate. I feel like that’s very sad. I want to be a voice that anybody could hear no matter what perspective they come from. I just want to give them Jesus and let Him sort out whatever He wants to sort out. The polarization is very sad and doesn’t represent Jesus real well.”

Listen to Evergreen here.

While women like Honeytree were creating their own space for representation within an existing culture, there was a group of women in a completely different segment of society creating their own culture.

Cris Williamson, who grew up in rural Wyoming, had cut her teeth on country-western music as a child and learned to play guitar and piano. She became entranced by folk music and made three custom albums—her first in 1964 at sixteen—before going to college in Denver, Colorado. “Judy Collins was a role model for me in many ways. The kind of material she chose to sing told me that there was a wealth of things to talk about, and alternate ways of saying them,” she reminisced in an interview with Shifta Stein in 1979.

After fronting a rock band and studying theater during her college years, she eventually landed in Sonoma County in Northern California. She was discovered by a manager while performing at a San Francisco folk club who independently produced her album and brokered a deal with Ampex Records, a diverse label whose roster boasted everyone from soul singers Doris Duke and Clydie King to the country music session group The Anita Kerr Singers.

Her self-titled major label debut, released in 1971, paired her with an impressive line-up of arrangers and musicians including Michael Zager, Alan Shulman, and Tom Salisbury, and most importantly, introduced a distinctive new singer-songwriter to the public. Ampex folded within two years of the album’s release, but its existence gave Williamson entré to performances on bills with singer-songwriters like Eric Andersen, Harry Chapin, and Jesse Collin Young.

It also made its way into the hands of Meg Christian, a Washington D.C.-based maverick singer-songwriter, who had been ruminating about the idea of women making music differently. She’d aimed to collect every album made by a woman as she looked for material that reflected the realities of her life as a feminist and lesbian. Cris Williamson had come into her collection and she began performing several of the album’s songs in her act. When Williamson came to Washington D.C., she made an appearance on a radio show co-hosted by Christian and Ginny Berson.

Williamson stood apart from Christian and Berson in that her political thoughts were not the driving force behind her work. In an interview with Ann Driscoll at Berklee School of Music, she explained, “I had no idea what women's music was. Feminism was still sort of theoretical at that point. There weren't very many books about women. And Meg had this idea, and they did an interview with me, and it was on one of the very first women's radio shows. They started asking me about sexism in the music industry that I had experienced. I hadn't had hideous experiences in terms of sexism. I've been lucky—fortunate in fact. It was men who had lifted me up and put me in the industry in the first place—had invested in me. I said why don't you start a women's record company? And they did the next day.”

What distinguished women’s music from the general pop market was its intention which was rooted in separatism. They wrote in an early advertisement, “We believe that women must become as possible from the male-supremacist economic system, and in order to do that, we must provide jobs for each other at living wages. We expect to employ only women in all aspects of Olivia. We will need engineers, producers, promotionists, financial managers, distributors, musicians, lawyers, accountants, etc….Olivia will be operated on a collective basis in which musicians will control their music and other workers will control their working conditions.”

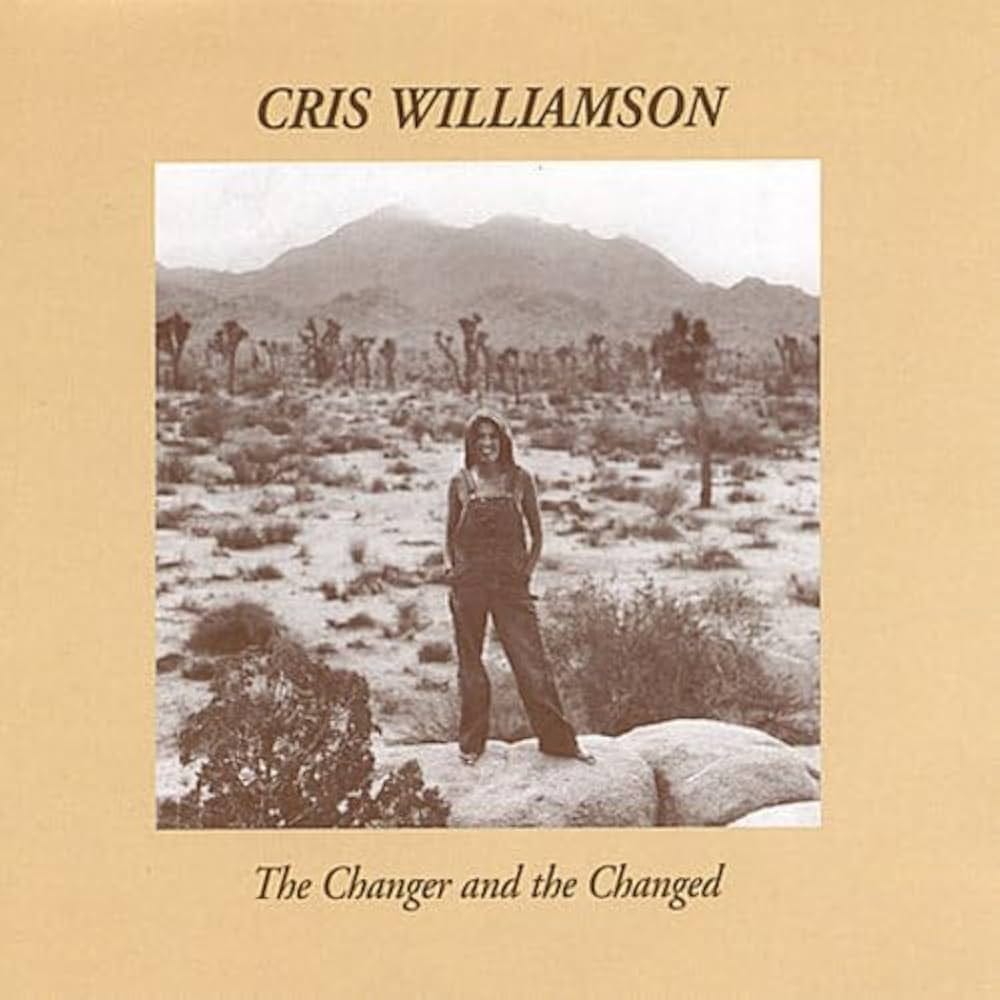

The label’s first release was a 7” single that featured Williamson on one side and Christian on the other, beginning a collaboration that would endure for nearly twenty years. Williamson lent her voice to Christian’s 1974 debut, I Know You Know, and when it came time to record her Olivia Records debut, The Changer and The Changed, Christian served as the album’s co-producer.

What turned out to be one of the best-selling independent albums of all time was recorded in a studio owned by a born-again Christian who Williamson says lent his studio to “a bunch of lesbians, a locked studio. So we could make our own mistakes and nobody could make us feel bad about it. And we did it and we learned how to do it! And we gave each other permission to do it. So we just made something up and it turned out to be a really viable alternative.”

While the album’s identity politics certainly lend it important weight, what has made The Changer and the Changed such an important piece of work is the music that it is composed of. From the chimes that sweep in its first seconds on “Waterfall” to the exultant last note of “Sister,” the album acts as a portal that transports the listener to another dimension for forty-three minutes.

The spiritual and emotional terrain of The Changer is deep and wide. “Waterfall” bridges the chasm between breakdown and breakthrough, invoking the familiar gospel idiom, “Everything’s gonna be alright.” Not unlike Laura Nyro’s compositional style, “Waterfall” is a composite of gospel, pop, and theater—navigating tempo and mood changes, beginning as a meditation and ending as a chant, guided by Williamson’s honey-like voice, acting as a salve to the wounded. “Wild Things” finds Williamson wrestling demons and “Hurts Like the Devil” has her lamenting a possible love that slipped away.

The alchemy of The Changer rests in the relationship between melody and lyric. Each composition seems perfectly aligned, not a lyric out of step with the music that accompanies it. Her spiritual romanticism, undoubtedly influenced by the unsung Judee Sill, unites the sacred and the secular in ways few have managed. “Sweet Woman,” a song from one woman to another, did this work so effectively, Christopher Kathman, a critic from LA Weekly wrote at the time, “my heart melted and my mouth fell open in shock.” He described the song as “an impressive piece of tunesmithing,” and her voice as one that should be “ranked among Streisand, Mitchell and Collins.” Similarly, “Dream Child” is a simmering missive that celebrates the union of the body and the spirit.

But for all of the richness of these songs, it’s in the directly spiritual music that Williamson’s core—what she once described as a “sacred, humanitarian place”—is even more evident, a component she expounded on in an interview for the Kansas City Times:

“Spirituality has been confined to a limited concept. To some, it means sitting on a mountain in India or praying in church, but music is spiritual too. Its effects are powerful, and it gets inside you, into places you thought were safely locked away.”

“Song of the Soul” is a modern hymn from Williamson’s pen that urges listeners to bring their entirety to the table of life, declaring a revolutionary affirmation: “You can be happy.” Replete with a choir of motley women, the song is an effervescent sing-a-long, but its lightheartedness should not undermine its depth. It is a continuation of the inner healing work that Changer is ultimately about.

The album’s last half works to complete that arc, viewing the pain of a sister-friend in “Having Been Touched (Tender Lady)",” the search for Self in “One of the Light” and then culminating Williamson’s second modern hymn, “Sister,” another composition that unites a choir of women invoking the feeling beneath the Women’s Movement mantra, “Sisterhood is powerful.”

The music for “Sister” was composed for a musical Williamson was working on about the life of the faith healer and evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, another ahead-of-her-time figure who dared to be, much like Honeytree, a woman on the male-dominated evangelical stage. When she crafted the lyrics for Changer, she found herself having to modify her lyrics to accommodate the expectations of the community in which she found herself. She shared with radio host Helene Rosenbluth in 1979 that the song contained a line that included the words “family of man,” but,

“…at the time, you couldn’t have the word ‘man’ anywhere near you, around you…it was one of the few concessions I’ve ever made in my writing. I didn’t feel great, but neither was I willing to haggle over [it]. ‘Family of man’ was a cliche and ‘of man’ was not the important part. Family was the important part. That was the concept I wanted to encourage. We’re in the human family whether we want to [be] or not….That’s what I’m trying to relate to—the world as it exists.”

Williamson maintained her individuality despite the pressures of the community that had most embraced her. While many desired her concerts to be open exclusively to women, she maintained a clear line, telling the Oakland Tribune in 1980, “I don’t do women’s-only events. They’re narrow and don’t fit into the reality of the world at large. I did that years ago because women wanted to feel what that was like, but once we got the hang of it, I wanted the audience to be general. I make music for everyone—women, men, and children.”

In the fifty years since its release, the album is estimated to have sold 500,000 copies and is lauded as the most significant Women’s Music release. Its relationship with the listener has only strengthened with time and Williamson has toured it in honor of its 20th, 30th, 40th, and now 50th anniversaries (Don’t miss the documentary, The Changer—A Record of The Times, below). In 2018, Cris and the Olivia Records collective received the Americana Music Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award, with Ann Powers citing Changer as the label catalog’s “crown jewel.” Williamson has since recorded a staggering thirty albums. Her most recent, Raven and the Roses, was released last year.

Chris I know and love. But how have I missed Honeytree? Now that I've heard her it feels like missing, as in "I miss you." Thank you for bringing her to us.