The Liberation of Leslie Phillips

How 'The Queen of Christian Rock' broke free from the world of Contemporary Christian Music

In the very first entry here, I referenced The Turning by Leslie Phillips, an album that came into my life in 1987 when I was eleven years old. I had not heard anything like it before. As an already-frustrated preacher’s kid, it was as if she had crawled inside my heart and mind, lifted the things I felt but didn’t have language for, and set them to music. With The Turning, I had the words and permission to feel those repressed emotions. “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,” she screamed on “Expectations.” Underneath the primal scream, however, was hope pointing towards another way of being and believing. As I have navigated life in the years since, The Turning and the music of Leslie, now Sam, Phillips has been a companion.

It had never dawned on me that I could, one day, simply leave the confines of my grandparents’ church or the larger institutional hold of Christian culture. Most of it grated against what I knew to be true about God and myself. The Turning changed all of that. Leslie bid the Christian world farewell in a May 1987 feature in Contemporary Christian Music magazine that preceded the album’s release. I read every word of that interview over and over. For years. Because she did, I knew that one day I would. The intellectual and spiritual quest were adjoined for her and that inspired me to become something other than heavenly minded. So, I share this history because its one that should be remembered, pondered over and meditated on.

In the 1980s, the possibilities for women within the framework of Christian music were severely limited to the confines of music defined as non-aggressive, middle-of-the-road. The most popular female vocalists in 1982 were Evie, Sandi Patti and Amy Grant and all three were identified as pop/adult contemporary artists. But there was a cadre of female artists, like Sheila Walsh and Wendi Kaiser of Rez Band, making space for women who desired a different form of expression. In 1983, Myrrh Records signed a twenty-year-old singer/songwriter named Leslie Phillips. Her work would trouble not only aesthetic convention, but, on a larger scale, theological assumptions about and within Christianity.

Phillips’ teenage years in Southern California were spent exploring the subculture of the Jesus Movement. While her family attended a more traditional Presbyterian church, she found her way to the core churches of the movement, Calvary Chapel, Church on the Way and Vineyard, the latter of which Bob Dylan was attending during his born-again era. Frustrated by the quality of the Christian music she was hearing on the radio, at thirteen, she began writing songs, “that would be in my taste both musically and lyrically, but would go a little deeper and talk about the hard times…when I first became a Christian, a lot of people I saw were real happy and I thought…Is there something wrong with me because I’m going through hard times and I’m not just praising the Lord through everything? I finally realized that you don’t have to be happy all the time.” Her early “gigs” were not in the typical venues. “I would do these weird underground gigs, not exactly in churches, but those kind of social activist functions. It was very bizarre. Those are interesting audiences to start out with—much more interesting than the club circuit. I would really sit and talk to them; you would never just sing and leave.”

When her debut album, Beyond Saturday Night, hit the market, Christian music press noticed Phillips’ depth and quest for writing beneath the surface. Carolyn Burns wrote in Contemporary Christian Music, “by the time Leslie’s first album was released earlier this year, the market—its steady diet of high glucose acts already buzzing through the airwaves—neared a fatal attack of the sugar blues. But when Myrrh Records served Leslie’s dish, it came with a knife and fork.”

The album was split between a handful of rock tunes and contemplative ballads that gave her suitability for Christian radio. Far from ambiguous, the album held a clear evangelistic center, with “Gina,” a song about a friend who died before Phillips had a chance to ‘witness’ to her about Christianity and “He’s Gonna Hear You Cryin’” which addressed depression and suicide. However, fundamentalist critics felt the message was unclear. Charisma Magazine wrote, “Phillips’ haunting, pretty album mentions the Lord, but one has to read the lyrics on the inside liner to know that the ‘You’ in ‘Put Your Heart in Me’ and ‘I’m Finding’ is capitalized, signifying it is directed at God.” They also noted that other songs had “messages that can be pulled out if one listens long enough.” The critic ends the review by asking “Can we really witness to the non-believer if we don’t say anything?”

In contrast to Sheila Walsh’s grittier album covers, Phillips’ artwork presented a soft, contemplative woman with long blonde hair gazing out of a window—and, most importantly, an image of her smiling on the back cover. Decorated with pink and light blue accents, the album further invoked the notion of a conventionally feminine artist.

After touring the first album with Phil Keaggy and Mylon LeFevre, two of CCM’s biggest stars, Leslie went back in the studio to create her second album for Myrrh, Dancing with Danger. Danger was musically and vocally more aggressive that the prior album. Campus Life Magazine described the album as “sledge-hammer singing (goodbye, vocal chords) and hyperkinetic music.” Lyrically, the album broached issues typically taboo within Christian music—premarital sex, body image issues and intra-group dynamics between women—but, in many ways, took a fundamentalist stance, one that stood in some contrast to her more introspective debut. In a 1985 press release, titled “The Queen of Christian Rock,” Phillips said that the album “refers to the way people, particularly Christians, dabble in sin.” She cited “Light of Love,” a song from the album about premarital sex, which she said “offers a totally different solution than you’ll get from today’s records or TV. My music encourages 100 percent dedication to the Lord.” Billboard, oddly, described Phillips as “gospel’s angry young woman” in their review of the album, calling her “a talent to be reckoned with.”

Despite Phillips’ espousal of conventional Christian moral views, she was still regarded as controversial. Her live performances drew particular attention from critics. USA Today described her as “shaking her long blond hair, silver chains and occasionally revealing her tummy.” The St. Petersburg Times wrote that “she sings like Pat Benatar, dances like Sheila E., and gives the gospel like Amy Grant.” Like so many artists, Phillips drew the ire of televangelist Jimmy Swaggart who, after writing of the above articles, said that “the whole issue of Christian singers and musicians—either male or female—exuding sexuality in either their public remarks, recordings or performances is antithetical to the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ. To be frank, it is blasphemous.”

In a 1985 appearance on the Today show, Jane Pauley questioned Phillips about her “sexy image.” Phillips told Contemporary Christian Magazine, “I felt the best way to respond—especially on national television—was to sort of avoid it because it is a loaded question. I mean, how do you really answer that? Yes, sexuality’s a part of all of us, but I’m not trying to flaunt that in concert. Yet I think that if I had tried to attack that in a short amount of time, it would have sounded like ‘I can too be sexy and be a Christian!’”

Sheila Walsh recalls Phillips’ performance at Gospel Music Week that year. “I remember…when she sang her song “Dancing with Danger” and she had on a red dress and she danced. I thought she was absolutely fabulous. I thought she’d shone. Yet, I was backstage when she got some of the criticism for being too sexy or flaunting herself. I remember just watching, it was like somebody taking something precious and just squeezing the life out of it, saying ‘This is not acceptable.’”

While Christian radio avoided Phillips’ rock-edged cuts, it made her ballads bona fide hits. Her first #1 single on CCM’s Adult Contemporary Chart, “Strength of My Life,” and “By My Spirit” were radio staples throughout 1984 and 1985, causing Dancing with Danger to spend twenty-four weeks on Cash Box’s Top 30 Inspirational Albums chart.

Philllips’ late 1985 release, Black and White in a Grey World, brought Phillips her greatest commercial success. The single, “You’re the Same” went to #1 on CCM’s Adult Contemporary Chart, while “Your Kindness” would go to #2. (Brother 179) The album climbed all the way to #3 on Cash Box’s Top 30 Inspirational Albums chart.

Black and White received rave reviews from Billboard, Campus Life and Contemporary Christian Magazine, but none seemed to detect the conflict within Phillips’ writing. Charisma Magazine, who had felt her first album lacked evangelical clarity, said that “Black and White in a Grey World will add color to the listening library of any Christian. With Miss Phillips’ piercing, demanding voice and lyrical renditions, it may just shake a few out of melancholy lives at the same time.” Even the more left-leaning Cornerstone Magazine, praised the album’s fundamentalism, feeling that it “underscore[ed] the true place of the Christian in this world as rebel.”

The title track reflects a commitment to being morally set to “black and white values,” scoffing at how the world had “no distinction, no emotion for right or wrong.” Yet, on “Smoke Screen,” she chastises the judgmental Christians, singing “When someone is wrong you write them off…never give a second chance…what if God had been that strict with you and destroyed you without a second glance.” Phillips says that these inconsistencies were the result of the record company “demanding dishonesty,” making her, as one critic wrote years later, “nothing more than a vocalist singing words she didn’t believe in over music she didn’t like.”

Her interviews between 1985 and 1986, however, indicate someone trying to step out of the imaging being created by her record company, which had dubbed her “The Queen of Christian Rock” in a 1984 press release. She began to speak out about the marketing machine of the Christian music industry and the perceptions of its record buying public.

“The big seller is the stereotype of the nice-little-Christian-girl-next-door who has dimples and is very nonthreatening and sweet. There’s some of that in me. I’m not weirdly artistic or anything. But there’s a thinking and artistic side of my personality as well. That stereotyped image of just being a little fluffhead for God is really doing God an injustice…I think that any woman who tries to be a little more thoughtful or tries to communicate things that are perhaps a little more edgy, a little bit more intense, is automatically assumed to be not as feminine or as good a Christian. There are still a lot of chauvinistic feelings in Christianity.”

In another interview the same year, she said “I have to resist the temptation to let some people’s judgmentalism change me…so many people think they’re authorities on Christian rock. They don’t look at you as a person, but as an object or a commodity to be judged. They automatically ascribe values to me that I don’t hold.”

Tom Willett was an A&R executive at Myrrh during Phillips’ tenure with the label. He remembers, “She showed up and did what the producer told her for the third record, which is not how I like to have an artist work. I sensed she was unhappy, but I couldn’t put my finger on it. The contemporary Christian music format wasn’t holding her back, but [when] we talked about the next record, I sensed all this intellectual, spiritual and musical growth.”

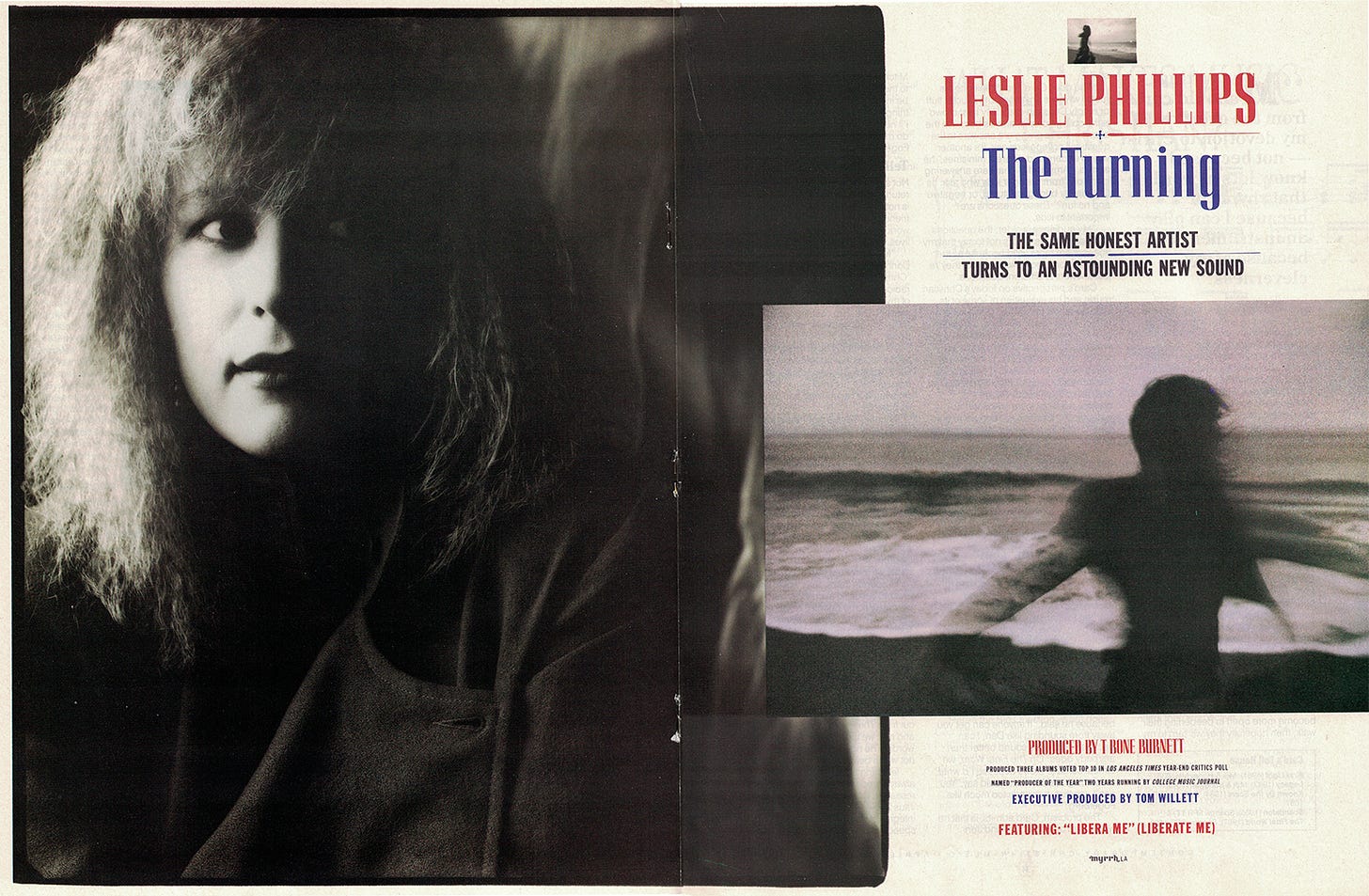

Willett paired Phillips with T Bone Burnett to produce her fourth album. Burnett first rose to notoriety in the mid-seventies as a member of Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue and as part of The Alpha Band—a group signed to Arista Records by Clive Davis. Their music was theologically Christian, but not fundamentalist. Burnett became a solo artist in his own right in the eighties, maintaining a connection with a small spectrum of Christian music lovers, but his intellectual fervor kept him at arm’s length from the larger, fundamentalist audience who patronized the Christian music machine. Their collaboration, The Turning, was released in the summer of 1987.

Just as the news of Jim and Tammy Bakker’s departure from their PTL Network and Heritage USA empire was breaking, the Christian music world would receive a shock when the May 1987 issue of Contemporary Christian Magazine hit the newsstands in April. “This is my last album for the Christian music market. This is the last,” Phillips told CCM. She explained the contradictions in the content on her prior album: “There was definitely pressure with the last album, and by pressure I’m not pointing the finger at any one person. Basically, I let the pressures get the better of me and some of those songs are sellouts. I didn’t do what I knew I should do. But I’m grateful I came to that point…I needed to go in a different direction.”

Where her prior albums had been comprised of answers, The Turning reflected her questions and frustrations.

Down

I hit the dirt when I see

who you really are

Down

All my strength leaves me like

A falling star

Cut to the heart I am opened up

Like a wound

Shattered convictions I thought

Were reflecting you

Down

Comes my religion like leaves

On winter trees

Down

You come to me with your love

On hands and knees

Phillips addressed this shift:

“I think I let myself be deluded over the last few years, that maybe things were a bit more black-and-white than they really are. A lot of it is just being young. I was 19 when I was signed to Word Records. How much of life have you really experienced at that point? And Christian audiences expect you to teach and be this incredible example…there was so much that was expected.”

The Turning indicated Phillips’ own self-possession, where her prior works had been, to quote a lyric from Black and White, a “tug of war.” It was also a defiant reclaiming of language. “Libera Me” speaks of the fear within fundamentalism—“I am dying from being held by hell…in a cell of blinding fear…Libera me from this dark dream to the life stream”—while “Down,” quoted above, speaks to the “shattered convictions,” the “black and white” she’d written of in the works she considered “sell-outs.” Only their shattering could lead her to a faith and love that transcends the borders that fundamentalism imposes. Word’s president, Stan Moser, is quoted as saying “The Bible most definitely addresses salvation, but it also addresses issues like honesty, integrity, homosexuality…specific songs can now deal with specific topics and that’s opened up a whole lot more freedom of expression lyrically and musically for our artists.” The freedom of expression, however, was only for those who towed the party line and maintained theological solidarity with the establishment. With The Turning, Phillips defied those borders.

She cited the work of mystic/theologian Thomas Merton as particularly important during this time, even reading a portion of his book Raids on the Unspeakable during her departure interview with CCM. She found Merton’s writings to be “very clear, very simple, very calm in the wake of all that had gone on in my life during those years.” Merton’s work, Phillips says, “was closer to what I feel: he embraced the mystical part of every religion and believed that those small corners were connected. And I believe that too.”

Christian music press across the board hailed The Turning as a triumph. Campus Life wrote, “in a music field choked by unimaginative sameness, their [Phillips/Burnett] collaboration, simply put, is not at all ordinary.” CCM called it “one of the best albums to ever come out on the Christian music market.” Outside of the CCM world, Rolling Stone reviewed the album and stated that “The Turning is far more generous of spirit than most secular-gospel records nowadays…Phillips’ songs are full of hopes dashed and beliefs threatened—for her, faith is a challenge.”

The reaction of her fans, however, was another matter. In what turned out to be her last performance in support of The Turning in May of 1987 at Knotts Berry Farm, “up to a third of the audience at each of the shows walked out—some of them angrily denouncing her new look, new musical style, or “unchristian” stage manner.” One attendee writes that “Leslie bounced out on stage with a very short mini-skirt, twirling around on stage in a manner that many in the audience found offensive…She primarily played songs from the upcoming album and the audience felt alienated and actually began yelling out songs from her catalog…Many left hurling insults and accusations at her as they left.” Mark Joseph, author of The Rock and Roll Rebellion: Why People of Faith Abandoned Rock Music and Why They’re Coming Back, was also in attendance at the Knotts Berry Farm concert and blithely contends—using chauvinistic language typically hurled at survivors of assault—that “I think she provoked it. She had this sexy outfit on, dyed her hair black and sang songs people didn’t know. I think she handled it wrong, but her objections were real.” Included in her set was “Expectations” from The Turning (in which she sings “Loosen the pressure you choke me with…I can’t breathe”) and followed it with Bob Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me Babe,” in which she sang, “I’m not the one you want babe…I’m not the one you need.”

According to Contemporary Christian Music, the Knotts Berry Farm concert set off “a rumor mill of unparalleled proportions. One festival where Leslie was scheduled to play this summer cancelled her appearance and Phillips subsequently called off all her upcoming concerts.” The rumor mill became so outrageous that CCM jokingly held a Leslie Phillips Rumor Contest in an attempt to use “humor to make a serious point about gossip; that ‘seemingly true’ rumors are just as wrong as the totally outrageous ones.”

In August of 1987, CCM reported that Phillips “has parted amicably from Myrrh Records.” In a 2009 interview, Phillips would say that “it was a good parting of the ways.” In an interview with Jeffery Overstreet, she would go into further detail about the reasons and the way she severed her relationship with Word.

"My record company was demanding dishonesty from me, saying weird things like ‘This song just sounds a little too sexy. We don’t know why, but you’ve got to change it. And no, we don’t know how you’re supposed to change it.’ At that point, it just got ridiculous. I said ‘This is ludicrous. I’m not going to continue with this label.’ At first they were upset and said ‘You have to. You’re under contract.’ I was selling well enough for them that they didn’t want to let me go. But I said ‘There’s a moral clause in my contract. And you know what? I’ve slept with someone that I’m not married to. And I’m not ashamed to tell anybody about that. And I will.’ They said ‘Okay, you’re free to go. You’re out of your contract.’ That’s how easy it was to get out of it. That’s how silly it was.”

“The label and the church I was attending at the time were worried that there was this young girl running around talking about Christianity who might not always toe the line, who was getting out of the barn and away from their control. They found it threatening. They were trying to rein me in, having me do secretarial work at the church to help put me under their control.”

But Phillips was out of the barn. By December of the same year, she’d changed her stage name to Sam Phillips and signed with the mainstream label, Virgin Records. Her first album, The Indescribable Wow, was released in 1988. Upon its release, she did her last interview with Contemporary Christian Music, reluctantly. The article’s author, Chris Willman, wrote that “Phillips felt that granting an interview at this point might constitute an endorsement of the gospel music industry she departed. But that reluctance was overcome by her desire to set the record straight.”

Once again, Phillips utilized the interview as an opportunity to re-direct language so often co-opted and claimed by fundamentalism, making distinctions between things often thought to be synonymous. “I think the so-called born again movement in this country has about as little to do with real Christianity as a Xerox of a hundredth-generation print of the Mona Lisa has to do with the real thing. The born-again movement is more about obsession and narrow-mindedness and repression—and true Christianity is about mercy and freedom and love.”

Since 1989, Phillips has recorded twelve albums, one of which was nominated for a Grammy Award. She scored the soundtrack for the 2000’s television series Gilmore Girls. She has also appeared in several films, most notably, Die Hard with a Vengeance, in which she co-starred as Katya, a non-speaking terrorist. She says that “most of the people I meet after shows who really want to talk have been through the same kind of thing. They started out with fundamentalism and have been on a journey for something more, for a spirituality that’s bigger, that’s attempting to be as big as God is or should be.” Her body of work as Leslie Phillips is still available in digital formats.

She continues to draw vitriol on social media and in YouTube comments from Leslie fans who did not follow her transition to Sam. They “miss the old Leslie” and lament that she has “completely surrendered to the world.” T Bone Burnett has said, however, that “She hasn’t lost the faith. She lost faith in Christians, in fundamentalism. But I consider that a good thing.” Phillips has continued to evolve. She says, “I feel at this point in my life that I can worship in a Buddhist temple just as well as in another kind of church. I might as well be in New Mexico looking at the mountains. I don’t feel I have to adhere to a certain regimen or routine or dogma.”

Like her contemporary, Teri DeSario, Phillips’ story serves as an important signpost in the history of faith deconstructionists, particularly in the world of Christian music whose historians paint its story with a broad kum ba yah-esque swath, crediting, largely, men for its story and editing out the dissenters. Thankfully, the stories of DeSario and Phillips disturb the spinning of that story. Their spiritual descendants—Jennifer Knapp and Nichole Nordeman immediately come to mind—continue the tradition of theological evolution and institutional interruption in a world where ideological compliance is required for platform and promotion.

Writer’s Note: I did not interview Sam Phillips, Tom Willett or T-Bone Burnett for this piece. Their quotes are pulled from insightful articles by Robert Wilonksy of the Dallas Observer, Jeffrey Overstreet of Looking Closer, Thom Granger and Chris Willman. Sheila Walsh’s quote is culled from my own 2016 interview with her.

To subscribe, click here.

Wow. Amazing article.