Albums with Landmark Anniversaries You Don't Want to Miss (1964-1974): Part 1

The Davis Sisters, William Morris O'Neil's Christian Tabernacle Choir, the New York Community Choir & Aretha Franklin all have LPs that turned 60 & 50 this year. I explore them in today's newsletter.

At the beginning of the year, I’d planned to write more extensive features on some of these albums. I ended up with more reissue/liner note work than I’d anticipated and the year got away from me…but I didn’t want it to end without bringing some attention of these great works that I haven’t seen anyone else write about. So, welcome to The Anniversary Edition, Part One!

60th Anniversary (1964)

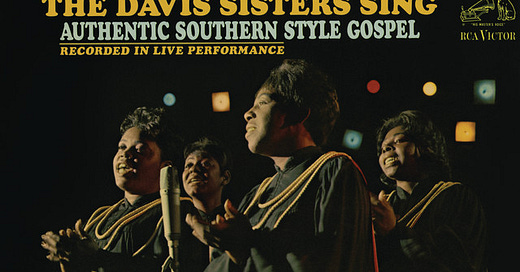

The Davis Sisters—Sing Authentic Southern Style Gospel—RCA Victor (1964)

In the 1950s, The Davis Sisters were one of the leading acts in gospel’s golden era. With hits like “Twelve Gates to the City,” “We Need Power” and “Shine On Me,” this group with roots in the Fire Baptized Holiness church brought sanctified fire, offsetting the Baptist leanings of many of their peers. Led by Ruth “Baby Sis” Davis, these hard-singing women are said to have made some of the male groups shake in their boots because of the ferocity of their delivery. But a series of internal issues and management problems caused the group to lose their footing as the sixties began to dawn.

In 1961, both Ruth and her co-lead Jackie Verdell signed deals to sing secular music, a shocking move for gospel singers. The Philadelphia Tribune reported that Ruth signed a blues deal with Columbia Records, while Verdell signed with Peacock Records. Ruth left the group for a moment (she would return in October of the same year, but leave again the next year) and during her second absence the remaining sisters along with Jackie Verdell (who had left the group for a spell in 1963) recorded this single album for RCA Victor. (Sidebar: Ruth’s blues recordings remain unreleased.)

For a set comprised of just five songs, The Davis Sister Sing Authentic Southern Style Gospel is a power-packed thirty-five minutes. From the bluesy-saunter of “The Man Is All Right” to the drive of James Cleveland’s “Oh Lord, Stand By Me” (led by Leila Royster Dargan), the album showcases just how strong the group was—whether Ruth was with them or not.

At the center of the album is Jackie Verdell’s sermonette which paves the path for Ruth’s signature song “On The Right Road” (Ruth would record this song with her group, The Davis Singers, in 1963). This fifteen-minute tour de force makes one wonder how Jackie’s pop career never took off…but also makes apparent just how much she impacted Aretha Franklin, who cited her as an influence in her memoir, From These Roots.

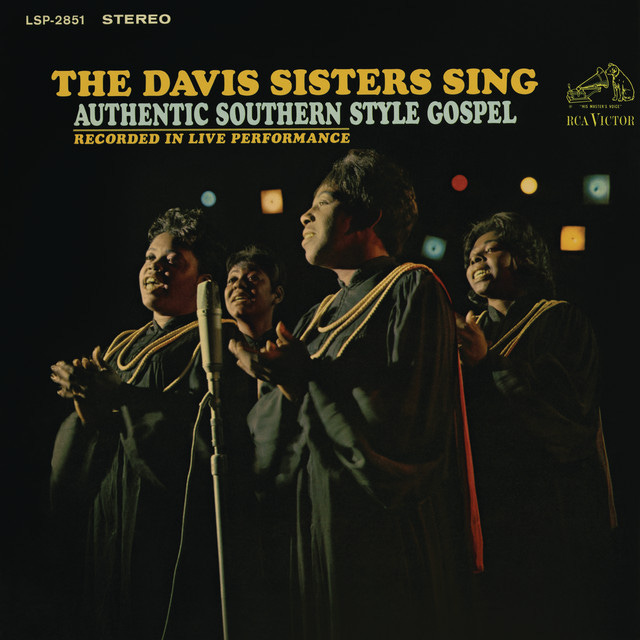

Bishop William Morris O’Neil & Christian Tabernacle Choir of Harlem—Swing Hallelujah—Elektra Records

Bishop William Morris O’Neil and his Christian Tabernacle Spiritual Church in Harlem plays a central role in my forthcoming book on the progressive theology and sound of the New York Community Choir.

After recording a series of sides for Hi-Lo Records in the 1950s, O’Neil’s choir (and congregration) recorded this vital historical document that—even in 2024—carries listeners back to Harlem circa 1964. While O’Neil was by all accounts a charismatic personality in his own right, his music department drew people in before they even had a chance to hear him speak.

A daughter church of Rev. Clarence Cobbs’ First Church of Deliverance in Chicago, O’Neil spread the sound in the New York Metropolitan area and established Christian Tabernacle as the place to be on Sunday mornings. Singers in the choir stand for this recording include Estelle Brown of The Sweet Inspirations, Benny Diggs, Arthur Freeman, and Wilbur Johnson (who were on the cusp of becoming Isaac Douglas Singers and founders of the New York Community Choir), Rose Hines of the Gospel All-Stars, and, likely based on the timeline, Carl Bean.

Swing Hallelujah covers the spectrum of the gospel sound, from anthems to hymns to blues to shout songs. O’Neil is undoubtedly the star of the set with his fiery “Wings.” Despite having spent the bulk of his youth in Chicago at First Church of Deliverance and his adulthood in New York, “Wings” is evidence that he never lost his Missouri roots. This recording gives us a glimmer into the magnetism he possessed that drew droves of congregants to Christian Tabernacle.

Other highlights include the choir’s interpretations of First Church signature songs like “Every Time I Feel The Spirit” and “Joy Bells.” YouTube commenters frequently misunderstand the commonality of choirs and groups covering songs popularized by others. There are all kinds of idiotic accusations of “theft” and “copying” that fail to pay attention to two important facts: 1) Christian Tabernacle was, as aforementioned, a daughter of church of First Church and was connected to the Metropolitan Spiritual Churches of Christ. There was a degree of uniformity within the organization—so that other churches within the organization were replicating and helping to amplify the sound of the Spiritual Church was not an act of thievery, but rather their duty and responsibility as affiliates of MSCC. 2) First Church’s Minister of Music, Ralph Goodpasteur, is credited on the album’s sleeve for his arrangements. Nothing about the song’s origins was obscured from the public.

Swing Hallelujah is one of the few surviving artifacts of the all-too brief period of O’Neil’s reign in Harlem and one you should definitely take the time to experience. LISTEN HERE.

50th Anniversary (1974)

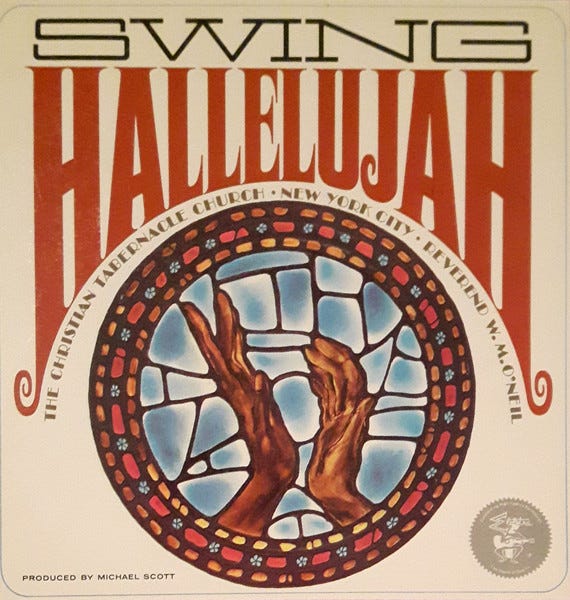

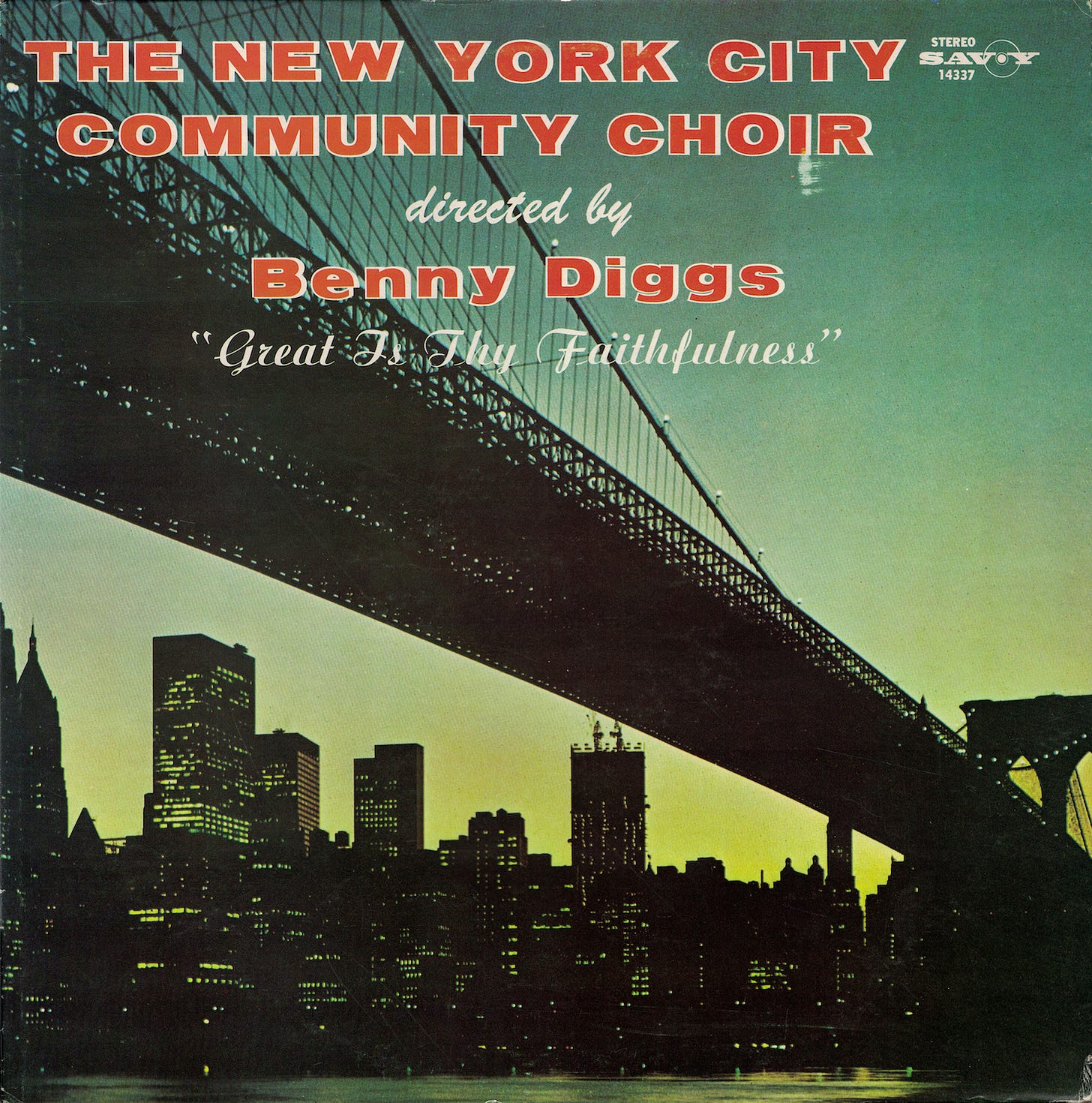

The New York Community Choir—Great Is Thy Faithfulness—Savoy Records

After two successful collaborative recordings with Nikki Giovanni and two albums of their own on Nashville’s Creed Records (the contemporary subsidiary of Nashboro Records), the New York Community Choir had accomplished what few choirs had been able to do—exist almost entirely outside of the framework of the gospel music community.

Their political alignment with the Black Power and Black Arts Movements brought them engagements on college campuses and at political events which earned them an audience of youths who understood the cultural significance of gospel music. While Edwin Hawkins’ group had taken to singing songs with a less traditional gospel sound and message (that’s not shade—I greatly appreciate what Hawkins did), NYCC maintained a sound that was firmly rooted in the gospel tradition and a message drawn from the progressive theology of the Spiritual church.

Their Savoy Records debut, Great Is Thy Faithfulness, marks the beginning of the choir’s second chapter. Ever a curator of great talent, the choir’s director and co-founder, Benny Diggs, had assembled a band of youthful innovators for this album like future gospel legend Timothy Wright and future Broadway musician/arranger Michael Powell (both of whom were central players on 1972’s A Little Higher) along with new talent like songwriters/choir members Vinson Cunningham and Sim Wilson. Leading the songs were NYCC co-founders Arthur Freeman and Wilbur Johnson and original member Fredericka Washington, daughter of Bishop F.D. and Madame Ernestine Washington, founders of Washington Temple Church of God In Christ.

Album highlights include “Lord Jesus Wash Me,” led by Arthur Freeman and Wilbur Johnson, one of the choir’s most enduring singles in gospel circles. Despite being a studio recording, there was no attempt made by producer John Daniels to distinguish it from a live recording, which is what makes this recording one of the most exciting in the NYCC catalog. “Sing Arthur Lee!” various choir members exclaim at various points in the song—and Freeman carries the song to higher heights. Freeman’s second solo, “You Shall Receive a Just Reward,” written by Timothy Wright, is another such high moment. To recognize that this entire album was recorded in a singular day with very few re-takes is to acknowledge the work ethic of the choir itself and the leadership of Benny Diggs as a director. Today’s groups and choirs should take notes.

While the gospel narrative today marks some of the other New York choirs as the most influential, Great Is Thy Faithfulness should be the album that helps bring the New York Community Choir back into the conversation.

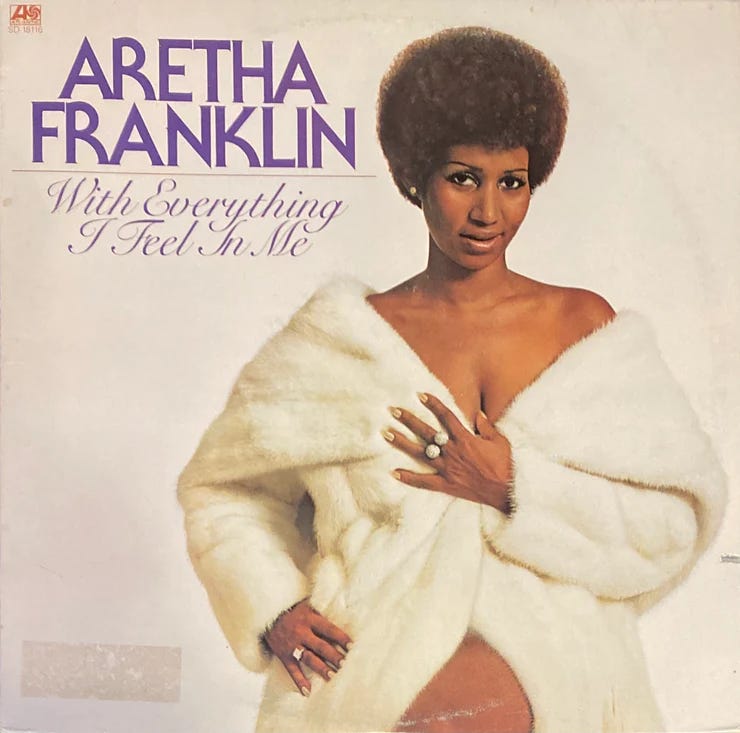

Aretha Franklin—With Everything I Feel In Me—Atlantic Records

When I think about revisionist histories, I instantly think about the ways this Aretha Franklin album has been stigmatized over the last few decades. The party line is that this album was a commercial failure and that it was unequivocally pummeled by critics. That is, in fact, not the case at all. Rolling Stone praised the album’s production and said the album “must be counted among the season’s very best pop LPs.” Similarly, a critic from one newspaper wrote that he’d “forgotten just what a fine singer Aretha Franklin is, but her latest set is a reminder of her range, feeling and sheer vocal elegance.”

While the album did not produce the kind of pop radio success that her previous release, Let Me In Your Life, had, With Everything’s first single, “Without Love” still climbed to the #6 position on the R&B chart. The album’s sizzling title track also made it to the Top 20 on the same chart.

But With Everything I Feel In Me marks a definite shift in Franklin’s intention. While her recordings with Atlantic up to 1973 had carried a certain cathartic, autobiographical quality, things began to change with the Quincy Jones-produced Hey Now Hey (The Other Side of the Sky). Not only was she writing more, but she was experimenting with a range of sounds and stories. Hey Now Hey flirted with an esoteric psychedelia and Let Me In Your Life had an elegance akin to Billie Holliday’s Lady in Satin. With Everything I Feel In Me carries less of the personal intensity of her early Atlantic work and more of her own understanding of herself as a premiere singer who desired to make vocal art. As funk and disco were beginning to emerge, Franklin began to change with the times—not unlike the ways Barbra Streisand was also adapting with that year’s releases The Way We Were and Butterfly.

While many would like to pigeonhole what the Queen of Soul was “the best” at, she proved in the decade prior and the decades afterwards that there was no music beyond her bounds and she was not afraid to Arethaize even the most beloved and definitive tunes. On this album, she deconstructs Bacharach and David’s “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” and “You’ll Never Get to Heaven,” both of which had been recorded by Dionne Warwick in the prior decade. While Warwick’s “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” marinated in a gentle swing, Franklin’s rollicks into the 70s with all the swagger of a Willie Hutch production. Likewise, she flips Stevie Wonder’s “I Love Every Little Thing About You” on its side, playing with tempo and melody in such an intense way that it is almost an entirely different song. These kinds of liberties are not a bad thing—in this writer’s book anyways. It’s an invitation into the mind of Aretha Franklin.

The real gems on this project come towards the end of the album. For the second time in her career, she records a secular composition by her friend and collaborator, the King of Gospel, James Cleveland. “All of These Things” is a simple verse and chorus, but it gives Franklin room to move, to brood, build and release, and then ride it out simmering.

Similarly, the album’s closer is a cover of Mother’s Finest’s “You Move Me,” originally recorded on their 1972 debut album. The original version, led by Joyce Kennedy, is a stunning performance by the band and vocalist, comparable to something you might hear on a Blood, Sweat and Tears or Chicago recording. It’s the kind of track some might even call untouchable. Never one to be deterred by perfection, Aretha heard it differently. Her arrangement is a little slower, looser and unabashedly vocally decadent, serving as a template for the kind of performance her disciples (most notably Luther Vandross) would build upon in their ballads.

While this isn’t the Franklin album to come to if you’re wanting songs like “Drown in My Own Tears” or “Ain’t No Way,” it’s a pivotal album in terms of Franklin’s expanded vision of herself as an interpreter, arranger and producer. While she famously liked having hits, her mid-70s period is a moment in which she redefined what it meant to be a vocal artist.

With Everything I Feel In Me is one of the handful of albums from her Atlantic years that is controlled by her estate. Here’s to hoping there’s a digitally remastered version (that will hopefully sport some of the unreleased material from these sessions) is on its way. In the meantime, listen on YouTube below.

In Case You Missed These…

New Time Religion: The Holy Ghost Falls Down in the Club

Writer’s Note: Thank you to A. Jeffrey LaValley, Loris Holland, Vassal Benford, Bennie Diggs and Preston Glass who shared their memories of collaborating with Tramaine Hawkins with me, and to David Nathan.

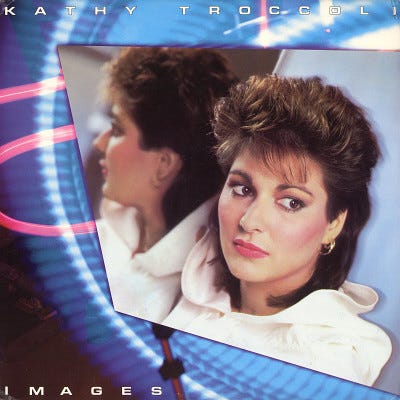

The Chance of a Lifetime: Kathy Troccoli's 'Images'

In the last newsletter of 2022, I wrote about Amy Grant’s recent Kennedy Center Honors acknowledgment and the reasons her revolutionary 1985 album Unguarded was a moment that represented ”the possibility of Contemporary Christian Music escaping the claws of the institution of the church that fitfully claimed it with the intention of re-shaping it into i…

The Glorious Gospel of Peacock Records [Expanded]

Thanks to all of you who have become paid subscribers to #GodsMusicIsMyLife! This newsletter is intentionally free for all—-there are no entries blocked by a paywall. You can support this work by becoming a paid subscriber for $8 a month. To do so, simply click here

![The Glorious Gospel of Peacock Records [Expanded]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!owpc!,w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3b7f0c4e-daba-4162-b5df-1ffa3ed69df0_1412x1098.jpeg)

Thankful for this thanksgiving weekend feast of music sand story!