New Time Religion: The Holy Ghost Falls Down in the Club

Reclaiming Tramaine Hawkins’ Mainstreamed Gospel

Writer’s Note: Thank you to A. Jeffrey LaValley, Loris Holland, Vassal Benford, Bennie Diggs and Preston Glass who shared their memories of collaborating with Tramaine Hawkins with me, and to David Nathan.

Tramaine Hawkins is an artist whose music has simply been there for the entirety of my life. I cannot count the times in my childhood that I laid in bed at night, falling asleep, crying, listening to her albums on my Walkman. My mother reared me on the Love Alive series, the Edwin Hawkins Music and Arts Seminar albums, and Walter’s solo project, I Feel Like Singing, all of which featured Tramaine.

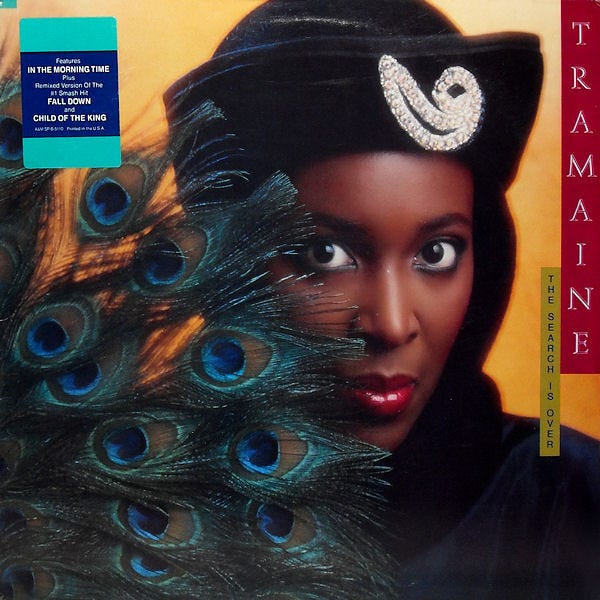

In 1986, when her The Search Is Over was released, she was more present than ever. The album’s first single, “Fall Down,” had hit the top of Billboard’s Dance Music chart in the early fall of 1985, something that had never been done before. Upon the album’s release, at 8:00 every morning for at least a year, Jim Gates and Rita Christie played her single, “In The Morning Time,” on their morning show on WCIE, which accompanied me on my ride to school, a Christian school where I was relentlessly bullied for being different. That album became a part of me—the moments of cruelty I experienced daily were met with her messages of transcendence, hope and survival. “You cared, you loved me, when I could not love myself, you were right there all the time,” she sang on the album’s title track. I found so much solace in those words as a bullied youth who felt entirely alone.

So, The Search Is Over has always held a special place in my heart. While The Winans and BeBe and CeCe Winans receive the lion’s share of the credit for gospel’s ultimate crossover just a few years later for their R&B chart-topping singles, Tramaine, like the New York Community Choir, the subject of last week’s feature, blazed the trail that made that success possible.

By the time The Search Is Over hit the racks, Tramaine had been recording gospel for twenty years. She made her debut as a teenager in 1966 in The Heavenly Tones, a group composed of young women (Tramaine, Sly Stone’s sister Vaetta Stewart, Elva Moulton, and Mary Rand, later McCreary, then Russell) from the Ephesian Church of God In Christ, pastored by Tramaine’s grandfather, Bishop E.E. Cleveland. Their first single, “He’s All Right,” was released that year on the Music City label (and was not produced by James Cleveland, as has been continuously erroneously reported). Later that year, they released the full length I Love The Lord on Savoy Records. But their run as a group was short-lived. When Sly Stone recruited the group to become Little Sister, recording both individually and as his background vocalists, Tramaine departed, not wanting to venture outside of gospel.

But her grandfather’s church was also home to another set of talented young folks. Edwin Hawkins directed their youth choir and his brother Walter as the church’s organist. When Edwin formed the Northern California Youth Choir and recorded “Oh Happy Day,” the original crossover song that took gospel to the pop charts, Tramaine was a part of the choir, leading “Joy, Joy,” a composition that would become a signature song in her career. As “Oh Happy Day” was met with both applause and fury, Tramaine toured the world with Edwin’s group, ambassadors of a new form of gospel, determined to take the music and message beyond the four walls of the church.

She had a brief stint recording and performing with Andrae Crouch & The Disciples in Los Angeles before marrying Walter Hawkins. Through Walter’s productions, Tramaine emerged as one of the most important and exciting voices in gospel music. Between 1975 and 1983, she was the voice of a litany of songs that would become staples of the gospel songbook, many of which were recorded live at Love Center Church, pastored by Walter. “Changed,” “Goin’ Up Yonder,” “He’s That Kind of Friend,” and “Jesus Christ Is the Way” were immediate standards in the Black church.

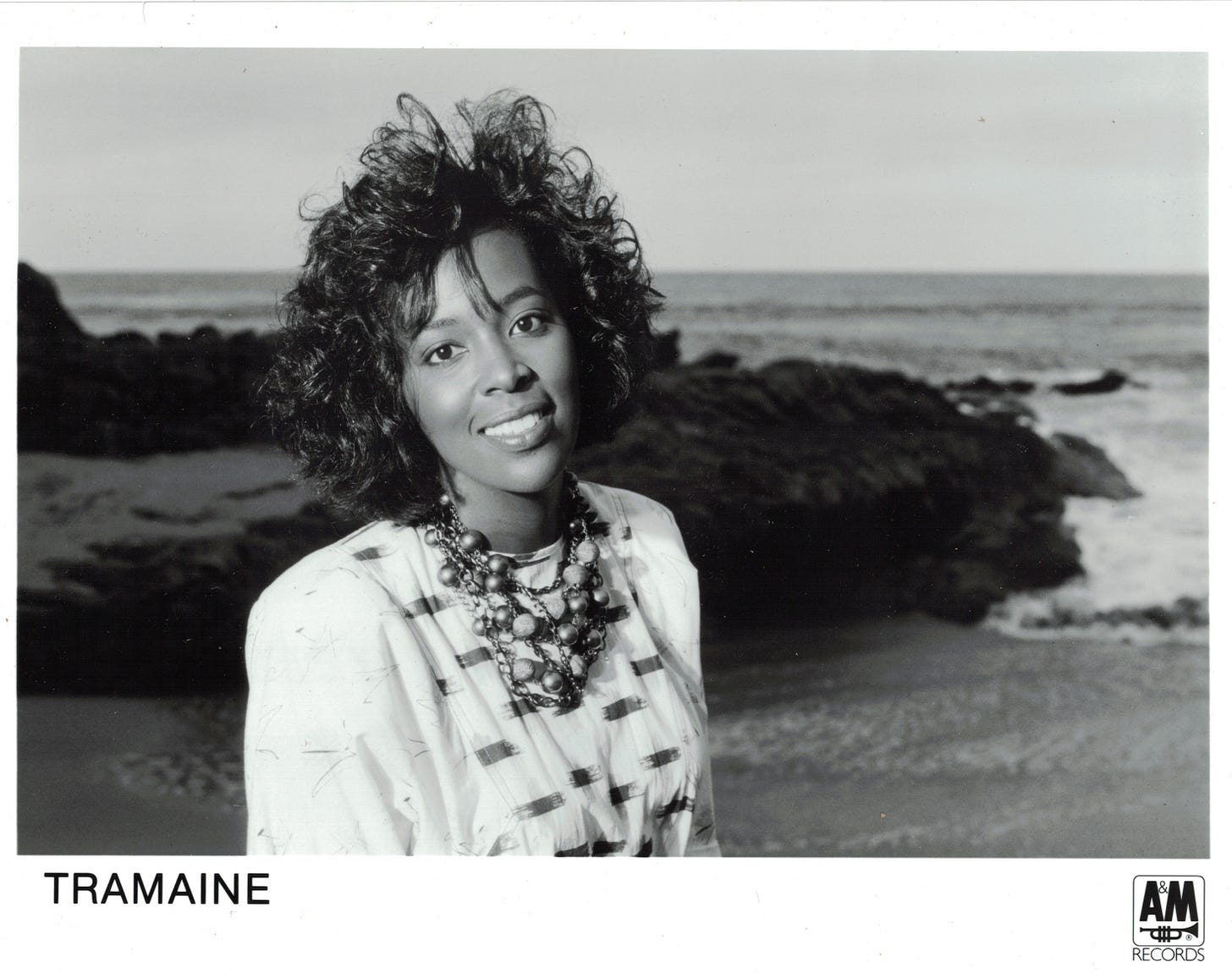

Her two solo albums, Tramaine (1979) and Determined (1983) proved that she had not only established a strong relationship with the gospel audience and had appeal to a wider audience with the white audiences of Contemporary Christian Music, but to audiences outside of the Christian world as well. She recalled in a 1989 interview with The Journal-News, “When I first got the offer from Light Records, I was afraid. I had been close enough to the industry to know some of the requirements—the total call on your life, being in the spotlight, giving an account of yourself, being labelled, being soloed out and on the frontline.”

Up until that point, on the road, Tramaine utilized a band directed by Love Center member, Daryl Coley. Coley had first appeared on the gospel scene in his teens in Helen Stevens’ Voices of Christ and as a featured soloist on multiple Gospel Music Workshop of America Mass Choir projects. By 1983, however, he was directing his own New Generation Chorale, doing background session work and served as musical director for Sylvester, famed for having taken the gospel sound and fusing it with an emancipated vision of sexuality and gender. Coley had composed the title track for Determined and his jazz-infused chords provided a new space for Tramaine’s voice to explore. Coley’s career demands left him unable to serve as Tramaine’s musical director as she prepared to take to the road to promote Determined. She would hire A. Jeffrey LaValley, another burgeoning gospel talent, to put together her new band.

While Tramaine promoted Determined, Coley recorded two duets with jazz legends Nancy Wilson & Stanley Clark, “The Two of Us” (which would turn out to be the album’s title track) and “Closer Than Close.” Both of those songs were co-written by a young, new talent, Vassal Benford, who had put together an instrumental track that found its way into the hands of Robert Byron Wright that same year.

Wright had emerged in the late 70’s as co-producer of the R&B band Pockets, whose 1977 debut single had landed in the R&B Top 20. He would work with the Jones Girls and Stargard, among others, eventually landing a position as RCA’s A&R Director of Black Music. His remix of Hall & Oates’ “I Can’t Go For That” would earn the band a #1 position on the Hot Soul and Pop charts in 1981.

In 1983, he was promoted to vice president of RCA’s Black Music Department. That same year, he produced the debut solo effort of Glenn Jones, a former Savoy recording artist as part of the Modulations. Jones stood out as a voice to watch and made the bold leap out of the gospel box for a mainstream deal. With Wright at the helm, Jones’ debut EP, Everybody Loves A Winner, boasted five songs that encompassed a Staple Singers’ brand of message music, focused on self-determination and the power of love. While it was clearly a mainstream effort, Jones was able to keep his gospel audience tuned in with the motivational messages of “I Am Somebody” (which Dr. Bobby Jones and New Life would re-record a year later on his Come Together album) and “Keep On Doin’” (a duet with his wife, Genobia Jeter, another former Savoy artist migrating into the R&B world).

With Tramaine’s contract with Light expired and her creative partnership with her husband, Walter, also changing as her marriage ended, she began to explore her new possibilities. In 1984, she and Wright, childhood friends, went into the studio to collaborate without the backing of a label. He proposed the track he’d received from Vassal Benford as the musical foundation. Benford recalls the source of the track’s inspiration being The Gap Band. “I’d met Charlie Wilson and I was actually writing this for him. And then Robert heard it and said it would be great for Tramaine. I thought, ‘Tramaine. Wow. She’s gospel...How would that work with traditional gospel?’”

Hawkins brought her musical director, A. Jeffrey LaValley, to New York for the first tracking session of “Fall Down.” “I was in the studio the night they recorded the track for ‘Fall Down.’ I said ‘Oh, I’ve never heard anything like this in gospel! This is not what I’m used to!’” They recorded Jonathan Dubose’s brilliant guitar work that evening, and the simmering guitar solo, LaValley recalls, was the result of melodic collaboration. “He had done the first half [of the guitar solo] and said ‘I don’t know what to do with this!’ I came up with the rest of it and said ‘Do this!’ That is a session I will never forget in my life!”

Wright’s vision was to reinvent Tramaine (he would dub her The Voice of the 80s), and, ultimately, create a new brand of gospel. The gospel fervor and message would remain intact, but the music underneath it would change. With background vocals by Fonzi Thornton (who served as vocal contractor), Philip Ballou (of the New York Community Choir and Revelation), Michelle Cobbs and Tramaine herself, the track served as the foundation for a blistering vocal from Hawkins.

But finding a label to serve as a home for this new sound proved to be a challenge.

Tramaine told reporter Lee Hildebrand, “We shopped it to every major record company for six months because I was a gospel singer. They felt the song was strong, but they felt the deejays were perhaps not going to play it.” Likewise, she’d talked with gospel labels, but Hawkins wanted to reach people not accustomed to hearing gospel music. “I did some seeking out of record companies. I leaned towards going someplace where my desire to make gospel music that could reach the masses could be realized,” she said to the Tri-State Defender.

“I’d gone to a number of record companies because I had a desire to try and create gospel music that could reach young people, but more often than not, they did not include any young people. The record labels just assumed that the secular audience didn’t want what we were offering—that it wouldn’t appeal to them.”

Finally, A&M Records offered her a deal for the single in 1985, not an album deal. Months prior, A&M had reached a distribution deal with the Christian label, Word Records, which included promotional dollars for their star, Amy Grant. A&M had taken Grant’s first mainstream single, “Find a Way,” to the Top 40. Tramaine’s single would serve as their second such venture.

In August, the twelve-inch single for “Fall Down (Spirit of Love)” hit the streets. The original “Vocal Version” is a smoldering eight minutes and twelve seconds of musical fire. Billboard’s Dance Music columnist Brian Chin wrote in the August 24 edition, that the single “is the kind of record that pushes us over with no problem. Built around a nagging synthesizer hook and hot, hot responsive singing. It sets a groove that just doesn’t stop.”

So immediate was the track’s acceptance, that it entered Billboard’s Hot Dance/Disco chart at the end of August and, just five weeks later, had hit the Top 5 and would, in the third week of October, take the #1 position. The song’s building success had made A&M take notice and Tramaine’s single deal turned into an album deal.

When she returned to New York for a concert engagement, she and Wright would meet Loris Holland, a musician that would become a key player in the album’s development. Holland was Minister of Music at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Brooklyn, which hosted Hawkins for a concert as “Fall Down” was beginning its climb up the charts. Holland remembers Wright watching him from the front row as he played. Holland was distinct in the gospel world as a musician with training in classical music (“I’m a counterpoint junkie,” he quips). After the concert, Robert approached Holland about working with him on the album that would become The Search Is Over. Wright had already conceptualized the epic “Heaven’s Gate” instrumental interlude that would open the album as a prelude to “Fall Down.” In Holland, he found the musician who could make it happen.

While “Fall Down” was a success from A&M’s perspective, it was wreaking havoc on Tramaine’s reputation in the gospel world. The press was celebrating the single, but buzzy headlines like “Singer’s Hot Gospel Seduces Disco Denizens,” and sensational blurbs, like the Village Voice’s declaration in their praise of “Fall Down'' that Hawkins was “in spiritual heat” were scandalous to her core audience in the church.

The single was also, however, strengthening the bond between Hawkins and another fan base she’d always had. The Hawkins Family had taken heat from the Christian world for performing at a Gay Rights Rally in San Francisco in 1981. Benford comments, “At the time, there was a big gay movement and with that happening, it just catapulted our song. It was great timing.” Indeed. As the New York Community Choir had discovered in 1977, the Black gay audience was enthralled with this eight-minute slice of the best of both worlds—a volcanic dance beat coupled with a vocal that had just as much rapture as Hawkins first big gospel hit, “Changed.”

“Crossover” fury was nothing new for Hawkins. After all, she’d been in brother-in-law Edwin’s choir when “Oh Happy Day” broke. In 1980, she talked with Contemporary Christian Music magazine about the criticism The Hawkins Family had received for working nightclubs in Las Vegas and the Playboy club circuit. “We were up there ministering and singing the same songs we would in church. Nothing new, nothing different. It was the same gospel and I know a lot of people were touched.”

This time was different though—the controversy singularly centered on her and was, in many ways, more vicious—loaded with misogyny and sexism. One Church of God In Christ minister made headlines when he insisted that, played in reverse, "Fall Down" was embedded with a message about having sex with God. “She’s calling this gospel!,” the minister exclaimed. Even without the internet, rumors of this sort spread and became more outlandish with each retelling. “Fall Down” co-writer/producer Benford says, “I wanted her to have big success with the record. I was just a young producer. I was eager to please. Working with somebody as great as Tramaine, I was in heaven. It was a big deal for me to see her hurt by it. It hurt me.”

Before the full album could even hit the market, she was in the midst of a vicious controversy. Holland describes her as being “crushed” by the hubbub surrounding the song and her new musical direction. He remembers Wright telling her, “You are going to go places where none of them can go. If we’re fishers of men, you can’t just fish in a Christian pond.”

For any who have experienced the ecstasy of Pentecost, the meaning of “Fall Down” was not a mystery. “Fall Down” was a celebration of the experience of spiritual transcendence. While the church insisted that that experience could only be attained within the sanctity of the four walls of the church, after hours of tarrying, “Fall Down” had the audacity to make that Holy Ghost power available to whosoever will, with no hoop jumping. “Heaven’s gates are open wide….just walk right on in,” she sang. There was no mystery as to what the song was about. It was an invocation of The Spirit. The sexualization of the song by the press is more the result of cultural and spiritual illiteracy than any innuendo in the lyrics. Additionally, it would seem that the utilization of that sexualization by the church to castigate Hawkins could be read as unspoken homophobia, because, at the end of the day, they knew who was dancing to the song.

Then, an invitation to perform at the Paradise Garage presented itself. The Garage was a haven for, largely, gay Black and Latin folks. With DJ Larry Levan serving as the minister of music, the Garage was known for creating an ethereal ambiance. Disco artist Taana Gardner told The Guardian, “I don’t think anybody ever can explain [the atmosphere of the Paradise Garage] exactly, it’s something you had to experience. It was just a freedom … an acceptance. There’s never been anything like it before or since.” It should come as no shock that Tramaine’s anthem was a hit there, of all places. “She didn’t want to go,” Holland says. “I was Robert’s ally—I was the church guy. I said ‘Tramaine, you’re doing God’s work. You’ve got to go everywhere.’' Holland says she listened to his argument and said “You’ve got a point.”

Holland accompanied Tramaine and Wright to The Garage. “She smoked it,” Loris exclaims. “They loved her. They freaked out! After she was done, she said ‘Oh, that was so good, but I feel like they’re gonna tear me up in the church.’ And they did. They tore her to pieces and it knocked the wind out of her.”

When the full album was released in early 1986, it allowed the world to see Wright and Tramaine’s full vision. Even a casual listen of The Search Is Over makes it abundantly clear that “crossing over” was not Tramaine’s intention.

“I don’t like the term ‘crossover.’ It paints a picture that you’re leaving something to do another kind of music. I never felt I left gospel music. No matter what I sing, or what the accompaniment is, I always sing about the Lord, about what I believe, above what I live for,” she told the Tri State Defender.

Hawkins’ A&R executive at A&M, Carol Cooper, wrote an editorial for Billboard in 1986 in which she articulated the importance of “widen[ing] the parameters of what is acceptable in the most popular radio and club formats.” She warned, however, that “the reality all mainstreaming candidates must face is the possible loss of their original audience.”

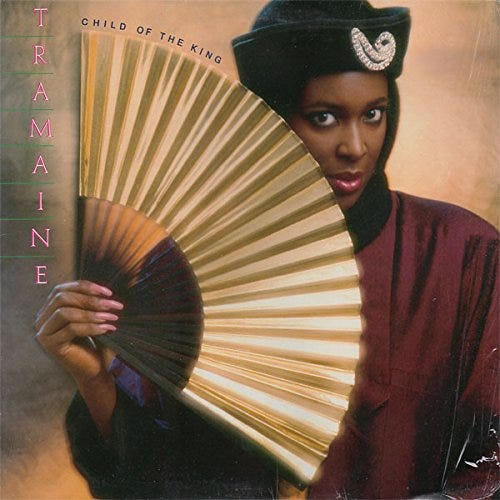

If the goal of The Search Is Over was to mainstream her message, Hawkins did that. She appeared on Soul Train and performed “Fall Down” (which would also crack the top 10 of Billboard’s Hot Black Singles chart) and the album’s second single, “Child of the King.” “In the Morning Time,” the album’s third single, would also chart on the Hot Dance Singles chart and its video would receive airplay on BET, VH-1 and a litany of video programming outlets. She continued to perform selective club dates, even doing that her way. She would perform “Fall Down,” but also “Holy One” and “Changed,” in her words to radio announcer Denise Hill, ”introducing those young people to real gospel.”

Every song on the album had a clear message directly related to faith. Even the album’s title track, written by Edwin Hawkins, about self-affirmation was pointing the listener to their belief system. In a completely different cultural context and with a different methodology, Tramaine was seeking the same end result as Amy Grant, her only peer in the mainstreaming of Christian music. Tramaine was, in a sense, singing gospel with refreshed theology and a modernized sound. Her theological upgrades were subtle, but clear. She told the Boston Globe, “Any changes that move in the direction of mainstreaming gospel music are positive changes. Adding a drumbeat or a saxophone to gospel doesn’t change the message. There is light in that music, and it doesn’t matter how you turn the light on. Your life just has to be in line with what you’re singing.”

Her rearrangement of W.H. Brewster’s “How I Got Over” (in a bit of irony, Tramaine’s version included Bennie Diggs and Philip Ballou of the New York Community Choir in the background choir) reveals one of these subtly loud revisions. “I want to thank Him for new time religion,” she sings, replacing the original composition’s “old” with “new.” Tramaine’s new time religion encompassed the all and made faith a possibility for communities who felt excluded by the mainline church’s religiosity.

Her rebranding of the hymn “Everybody Ought To Know,” (arranged and co-produced by Walter and Wright), seems the perfect climax to this manifesto of an album. She was, indeed, the same Tramaine who rendered “Jesus Christ Is The Way.” She merely upgraded the presentation, bringing every bit of her gut-bucket gospel to Wright’s innovative sound, bringing new life to a song that hadn't ever had this much energy invested in it. Her sermonette in the song’s vamp is, indeed, the personalization and articulation of the album’s message. “I’m not just a singer of lyrics,” she told me in a 2007 interview. “I get in there and do my homework. I take a song and I’ll do my own ad-libs. I’ll preach it, in a sense. It has to be something I’ve already experienced and I can really preach that song and tell that story.” And that’s what she does in “Everybody.” “I came to tell you,” she growls, “you oughta know him, yes you should!”

I would be remiss if I did not mention the glamour of Tramaine. In addition to the voice, it had been her fashion sense that had always set her apart from the beginning, with multiple critics noting that she looked like she’d stepped off the pages of Vogue. She upped the ante on The Search Is Over, with a cover shot that served Dynasty realness, complete with peacock feathers and a gold fan (which she also took with her to Soul Train), a new time answer to the old time church fan.

“People think gospel singers are supposed to be in robes. They’re supposed to be heavyset, looking up and pointing to the sky, pointing to the Lord. I was the first to look dead-on. I had my makeup and I had my nails and I had my little rhinestone jacket. I said, ‘Come on!’” she told USA Weekend in 1991.

The follow-up album, 1987’s Freedom, however, proved a challenging experience. Robert Wright finished writing and demoing the songs with Loris Holland, but died of AIDS-related complications before the project began production. Robert was, by all accounts, more than simply a music producer for Tramaine, he was a trusted friend and was advising her career. Vassal Benford says, “Robert was very passionate about Tramaine and getting her project done. I think [his death] affected Freedom a lot. He was the guy who could have kept Tramaine okay during the time of this transition, of us creating a new platform for gospel music. He would have been that guy that would have assured her that everything was going to be ok and that we’d just created the future and she was ahead of the curve.”

Benford was reunited with Tramaine for two songs on the next album (“Freedom” and “Power,” both co-produced by Benford with Tito Jackson), but he describes a tense recording experience. “Tramaine was quite upset when she came into the studio with us...especially me. We had put her in a position where she had to do this non-traditional club music.”

Benford says that he envisioned the new songs in a more R&B vein, and less in the club direction. “I wanted her to feel better and more traditional. It didn’t do as well, but I think it made her feel a little better. I don’t know if they forced her to record with me [or not]. I just said ‘Let me get something great done with her’, but I didn’t give the record the same energy I could have because I was being careful with her. I didn't want her to experience the same situation twice.”

Preston Glass, whose production credits up to that point had included artists like Jermaine Stewart, Stacy Lattisaw and Kenny G, was brought on board for “Love Is Blind.” “I remember saying that she sounds best when she can sink her teeth into something, when the groove lets her breathe a little. We wanted to give her something that wasn’t so frantic so she could just sink that voice into it.”

Of all of the songs on Freedom, “Love Is Blind” is the throughline, the song that most deeply connects to Tramaine’s larger body of work. Like “Call Me” on her debut, “We’re All In The Same Boat” from The Joy That Floods, or “I Don’t Wanna Be Misunderstood'' from 1994’s To A Higher Place, Tramaine has always included reminders of our kinship as humans, the importance of that universal connection. Wright, Preston and his brother Alan wrote in “Love Is Blind,” “So we say in God we trust, then won’t take our brother’s hand. There’s no fault, too great or small, we won’t find a perfect man,” which seems to speak to Tramaine’s experience with the church in the events surrounding “Fall Down,” and the rejection many of her fans were experiencing as the AIDS epidemic was wreaking havoc on gay communities.

The title track was released as a single to the clubs, as was “The Rock” (complete with a Larry Levan remix), but neither caught fire. All of the slick packaging that helped make The Search Is Over a sensation was not something A&M invested in this time around. “I liked Freedom, I thought it was special. They did a terrible album cover. It was like they didn’t care and they basically shelved her, which was terrible. She had no help,” Loris reflects.

But Tramaine rebounded and rebranded quickly. James Cleveland brought her to the Gospel Music Workshop of America, embraced Hawkins and chastised the audience, composed of gospel music’s gatekeepers, instructing them to support, not judge, and pray for creative, innovative people. She signed with the Christian label Sparrow Records in 1988 and released a traditional gospel project, The Joy That Floods My Soul. Two years later, she’d record the Grammy-winning Tramaine Hawkins Live album, which would complete the work of mending the rift with the gospel audience and solidify her place as a bona fide gospel legend.

When asked, for years, about the A&M years, she’d say little. In 1989, she told The Journal-News, “I don’t like to talk about that particular time in my career. It was very taxing emotionally. I didn’t expect to get criticism to that extent. I never did or said anything that didn’t give glory to God on Soul Train or other places that gospel artists don’t usually go. I gave my testimony in closing with my song. Being a forerunner, I got a lot of flack. The main thing to remember is that a lot of young people were listening to that song. A lot have written to me and are now in the church. They listened to ‘Fall Down’ and were drawn to that.” The same year, when talking with the Tri State Defender, she said,

“When I started recording for A&M Records a couple of years ago, there were few, if any, other artists who were mixing an inspirational message with a dance beat. It felt like I was totally alone. The original idea to do “Fall Down” that particular way, I must add, came totally from the record’s producers.”

But younger artists, like BeBe and Cece Winans and their brothers, The Winans, would come along and take the same heat she took as they carried gospel to the top of the R&B charts. While riding the success of Tramaine Hawkins Live, she told the Toronto Star, “I laugh when I think that 20 years ago, I was considered radical, and now they call me traditional. In some ways the route I’ve taken has opened the road for other contemporary gospel groups like the Winans and Take 6, but the funny thing is, the established church still hasn’t completely accepted what I do. To some of them, I’m still a radical.”

And in many ways, despite her musical return to traditional gospel, she was a radical. She was one of the few gospel artists who worked on behalf of the Minority AIDS Project and other AIDS-related projects. She remained an advocate. In 2006, she contributed an essay to Not In My Family: AIDS in the African-American Community where she wrote of losing Wright and others in her life to the virus. Her remarks stood deeply apart from the mainline traditionalists who’d also vilified her for “Fall Down.” “As a society,” she wrote, “we hide a lot of things that we don’t want to look at. It’s unfortunate that we’d rather hide from homosexuality than embrace it.”

Every time I hear The Search Is Over and Freedom, I wonder what might have been had Tramaine been able to create without concern for what the jury of the church might say or think. What if she’d been able to go to the Garage and other clubs to share her gift without the gnawing, internal dread of what awaited her in the form of rumor, character assassination and economic consequence, when she returned home or to her next church engagement? What kind of creative fulfillment has she really had in the years that followed those albums knowing the boundaries her audience expected her to abide by? What if she hadn’t had to feel so entirely alone in the mainstreaming endeavor, to merely take a message of God’s unconditional love to the world?

In 2007, she released her most recent project, I Never Lost My Praise. On a television appearance with Juanita Bynum, Bynum said of Tramaine, "That's real sanging for the Lord. That's singing from another place.That's not talent singing...that's an experience that's wailing out." I hope that now, in 2021, Tramaine’s A&M works can be revisited and understood as part of the experience that she has always been pulling from, whether that was in the Paradise Garage or West Angeles Church of God in Christ. While Tramaine is now considered a traditional artist, it is diminishing to relegate her to just that. She also stands as a reminder of the emotional depth that is undeniably absent in the wake of worship music’s consumption of both contemporary and traditional gospel. Vassal Benford remains proud of what they accomplished. “We were before Kirk Franklin and Mary Mary. At the end of the day, we changed the face of gospel music with ‘Fall Down.’ We changed the trajectory of gospel music.”

Have you subscribed to God’s Music Is My Life? If not, click here.

Not only was I huge fan in the 1980s of the 12" singles from The Search Is Over...I still listen to them with fair regularity! They are timeless. The songs are incredible, and the sound quality is pristine -- sound quality that's very difficult to come by these days. I also have the 12" singles "The Rock" and "Freedom," which were disappointing in comparison. This informative article reveals the story why. So sad.

Thank you Tim, I learned so much from

your piece!