Unguarding Amy Grant

Reexamining the unprecedented album that put Amy Grant alongside Madonna, Huey Lewis, and Duran Duran in the pop zeitgeist

There wasn’t a bigger artist in Contemporary Christian Music in 1985 than Amy Grant. The eighties had slowly, and a bit unpredictably, become hers. Amy was still in high school when her career began in 1977, singing a mix of her own compositions and well-crafted, radio-ready hits by other writers like “My Father’s Eyes,” the title track from her sophomore album of the same name, which began the real work of establishing her as someone to watch within the field.

But there were hurdles to overcome. Her musical identity was uncertain, the early albums uneven. Her third album, Never Alone, had confused a fragile audience, who even called some of the album’s sonic experimentation “drug music.” While the album had an edgier sound and a deepened lyricism than her first two, the teenage naiveté of her prior works lingered, keeping new listeners at bay. Her management, in a smart, strategic move, put her on the road with the Memphis-based band, DeGarmo and Key, whose sound challenged her. Her prior tours had been acoustic, so some of her early songs like “Old Man’s Rubble,” and “Beautiful Music” came alive differently on stage, giving Grant the opportunity to develop as a performer and nurture a deeper relationship with her audience, unconstrained by her guitar.

Wisely, that tour was recorded and released in two live volumes in 1981, giving Grant a year to reinvent. The live albums placed some distance between Amy the adolescent and Amy the young woman, who was taking stock of her platform and what she wanted to accomplish by way of it. “I’m Gonna Fly,” one of the new compositions that opened In Concert Volume II gives listeners an idea of the kind of self-evaluation she was contemplating. “I have felt for the first time I can be myself, no more faces to hide behind,” she sang. The girl with her father’s eyes was becoming her own woman. “It got to the point where my own mother had to tell me, ‘Amy, you’re not even reaching your own age group.’ She would rather have me playing the kind of music that is going to reach people. I have to admit that before I was a Christian I would not have even listened to myself playing the kind of music I’ve been playing up to now,” she told Contemporary Christian Music magazine in 1981.

Her subsequent releases from 1982 to 1984 [Age to Age, A Christmas Album and Straight Ahead] reflect production that was paying attention to what was happening on Top 40 radio and a multi-focused lyrical approach. While songs like “El Shaddai,” “Jehovah,” and “Emmanuel” provided the Christian market with the directly spiritual material they required, she was able to prove that she could write material about life that might have possibilities outside of the Christian world. Compositions like “Open Arms” and “I Love a Lonely Day” were the kinds of songs that the watchmen in the church who had no time for the ambiguous ‘You’ raged over, as ‘You’ (always with a capital y) could easily be a boyfriend or Jesus.

But, the risk paid off. 1982’s Age to Age was the first CCM album to be certified gold by 1984 (later platinum) and remained the best-selling Christian album a year and a half after its release, winning a Grammy and two Dove Awards. The New York Times called her The Michael Jackson of Gospel Music, she packed Radio City Music Hall and had a multi-page feature in Life magazine when 1984’s Straight Ahead was released.

As Grant and her team toured Straight Ahead, however, she was watching her audience and thinking about the next steps. For as mainstream as she seemed to the insulated Christian audience, she appeared “heavy-handed and naive” to a Billboard critic who reviewed the Straight Ahead tour’s stop at Nashville’s Tennessee Performing Arts Center. They also noted that “the concert seemed controlled and bloodless.” This would, of course, make sense coming from a critic accustomed to seeing audiences dancing to the music--but in the Christian world, in certain places, simply clapping was a matter of theology.

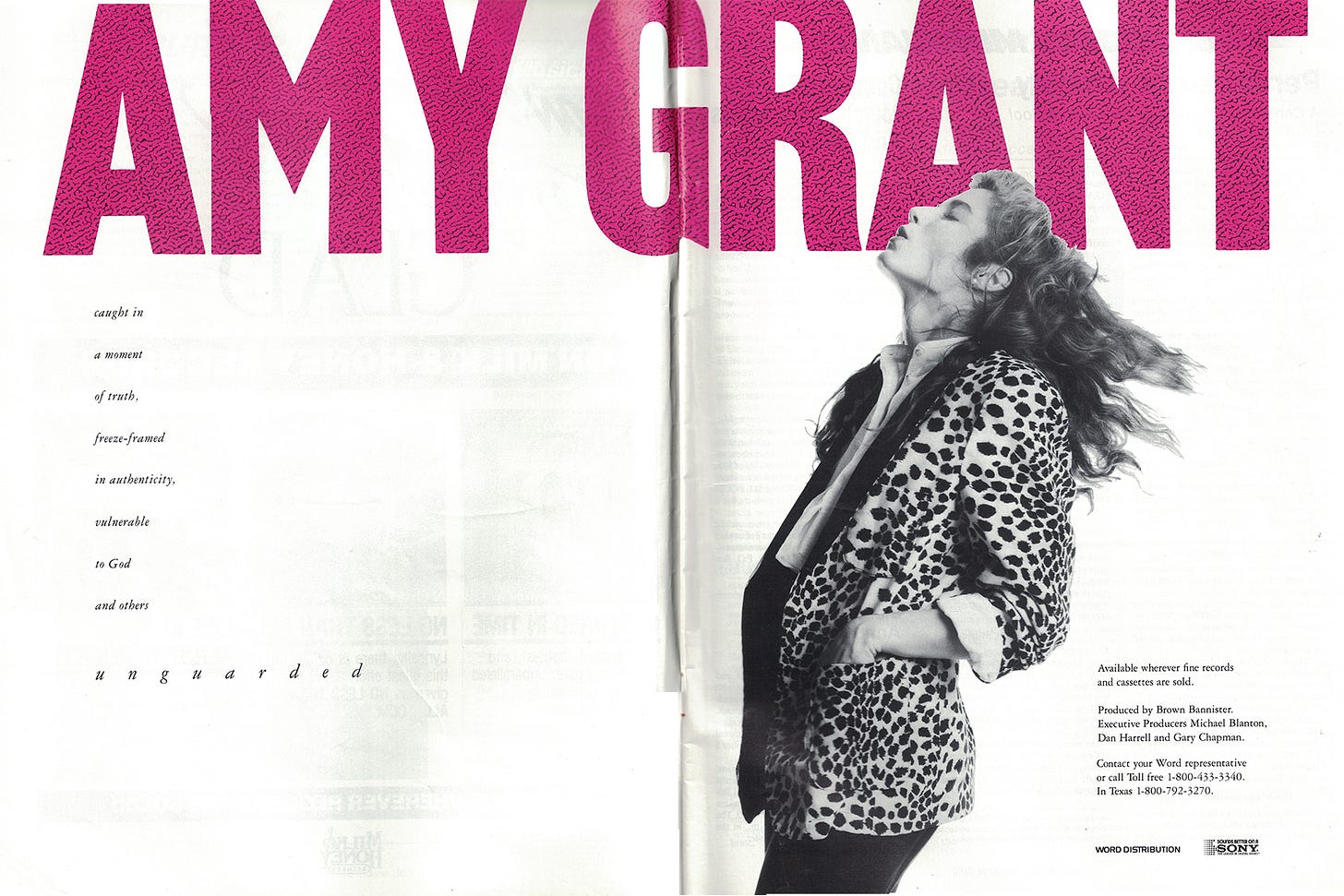

Ironically, the movie Footloose was in theaters as Grant’s troupe was on the road. In the liner notes for the 2020 reissue of Unguarded, Michael Blanton, Grant’s co-manager at the time, writes that it was seeing that film, the story of Ren McCormack’s quest to legalize dancing in the ultra-religious small town his family had moved to, that inspired their next steps. “We have got to make some music that allows Christian kids to have fun, and to dance with music that has more energy,” he recalls telling their small circle.

But circumstances would take Blanton’s vision of music for “Christian kids” a bit further.

Amy had been signed to Word Records’ Myrrh imprint since the beginning of her career. Word had also long been envisioning crossover success. The Imperials’ “Living Without Your Love” and Benny Hester’s “Nobody Knows Me Like You” are examples of songs the label had used in years prior to dip their toes in the waters of mainstream radio, but Amy’s appeal and sales numbers were something that made Christian music something of interest outside of the Christian world. An unprecedented distribution deal between Word and A&M Records had been reached as Grant and company were working on the album that would become Unguarded. A&M was willing to put promotional dollars behind her next effort (It’s important to note that A&M was simultaneously working on another crossover effort with their own signee Tramaine Hawkins, who will be the subject of next week’s feature). A&M President Gil Friesen told the Los Angeles Times that he’d been “wary” of Amy, but had seen her at sold-out Radio City Music Hall on the Straight Ahead tour. “After the show, I was a fan. She’s that good. Christian or non-Christian, she has a rapport with the audience. She’s a hit artist. She’s a star. What she sings and does on stage transcends a category.”

The last album to be recorded at Denver’s famed Caribou Ranch, Unguarded would, undoubtedly, make history. After the Word/A&M deal was final, Amy told Musicline magazine prior to the album’s release, that she and her team re-evaluated what they’d recorded for the project up to that point. “We were getting ready to cut this song ‘I Know You’ and, all of a sudden, I thought ‘I Know You’ was fine, it was truth, but it was so safe, I wasn’t being vulnerable. If I’m expecting the audience to be vulnerable, I’ve got to be vulnerable. Yes, it was a song about God, but I don’t know what God thinks. How can I write a song from God’s perspective? I thought, why am I writing this?”

And vulnerable she was. “You know some days I like me, some days I don’t,” she declared at the beginning of “Fight.” “Got myself in this situation, I’m not sure about,” she confided in “Wise Up.” “Now the truth has hit us, life is very hard,” she confessed in “I Love You,” written for her then-husband Gary Chapman. The confessional songs were offset by story songs, parables, if you will, like “Sharayah” and “Who To Listen To,” that relayed spiritual truths in relational terms, not spiritual ones. She wasn’t proselytizing, she was building rapport with both her existing audience and potential new listeners.

“The Christian community is starting to understand that, yes, there are singers who only want to choose to sing for the church, and continue to exercise the lingo and promote the phraseology, but then there’s a group of us that say ‘I believe in Jesus, he’s changed my life, and I want to be a part of my culture,’” she told the Los Angeles Times. For as tame as that premise sounds, it was, indeed, controversial, even to lovers of the already-controversial world of Christian rock. CCM had, in just a little more than a decade, become a subculture of separatists. Artists like Grant endangered the safety of that insulation.

When the first single from Unguarded, “Find a Way,” hit mainstream radio airwaves, she was seemingly everywhere: VH-1 put the video in rotation and she hit the circuit for morning and late night television. There were countless newspaper features not only about Grant, but Christian rock, a form that had, largely, remained hidden from the mainstream world for most of its existence. The single began climbing Billboard’s Hot 100 and Adult Contemporary chart, officially placing Amy in the world of pop, alongside Madonna, Huey Lewis and Duran Duran.

The critics, both from Christian press and the mainstream, grappled with an album that was unprecedented in both spheres. Christian music had created a box that limited the ways it could be heard and the places it could be seen, and Amy was smashing that box. While pop critics seemed to largely agree that the album was breaking no new musical ground when compared to the pop albums ruling the chart at the time (Madonna’s Like a Virgin or Prince’s Purple Rain), it was groundbreaking when it was considered as a Christian album intended for the pop market. Esquire’s Mark Jacobson counted the number of times she mentioned god or Jesus in the lyrics (twice), but argued that “it would be a mistake to assume this makes Unguarded any less of a Christian record. Rather than being less Christian, it is as if Christian-ness permeates the material to such an extent as to make the mention of it redundant.” Ultimately, Jacobson understood the essence of the album’s intention--pop music with a Christian ethic.

Christian critics, however, recognized that the CCM audience may not be willing to exchange hearing the explicit messages they demanded for that intention. Artists had been skewered for not saying Jesus enough in their songs, some for having too many shirt buttons undone on their album covers, and the Christian reviews of Unguarded seemed to be anticipating the outcry of the ardent. The Contemporary Christian Magazine review closed their review asking their readers, “Are we in this business to stroke the body [of Christ] or to take the message to a dying world? With Unguarded, Amy Grant takes the message where it's needed most.” Many readers, however, were predictably hyperbolic in their response. “Amy has sold out. What a disappointment! I can honestly say that Unguarded is contemporary but it is not Christian. Even the cover gives it that pop-rock seductive look.” She spoke directly to the criticism she faced from the Christian world speaking their language. She told the Los Angeles Daily News,

“When I read the New Testament, then look at the conservative church of America in 1985, I find that so many of the things the conservative church upholds to their dying breath are not in the Testament. At times, I find myself thinking that I don’t understand the scale of judgement by which I’m being judged. I can’t find it written down anywhere. I can’t find the scale.”

But at twenty-four, Amy was, perhaps even unknowingly, at the vanguard of progressive Christian thought. Her desire to establish a presence outside of the church, “in the culture,” as she put it, countered the very notions of apart-ness that permeated Christian industry. While Jim Bakker was establishing his Heritage USA as a place for Christians to vacation, shop and be entertained, safe from the dangers of “the world,” Amy was interested in doing the opposite. In a 1986 feature in CCM, she expounded on this mission: “I really want to be a voice in my culture. For those who would hear it, I’d like to tell them about Jesus, and for those who aren’t ready to hear it, I’d like to still have a message of hope. I’m trying hard to understand human nature. I think if we understood ourselves better and understood each other better, it wouldn’t be such a trauma being here.” This counters even the CCM critic’s view of Amy as a Christian missionary taking a message to a “dying world.” Amy’s understanding of shared humanity is, perhaps, why she remains the only long term crossover success story to emerge from contemporary Christian music.

While there was buzz that other CCM artists, like Russ Taff and Petra, would find similar success, the 1985 Word/A&M crossover experiment was short-lived. Roland Lundy, Executive Vice President of Word Records told Billboard in a 1986 interview, “I’d be less than frank if I didn’t admit that we have gone to them with certain product that we thought they could do something with--and they’ve elected to pass on it.” It’s evident that Word-distributed artists, in particular, sought to replicate Amy’s path. An Unguarded collaborator, Chris Eaton (whose songwriting credits already ranged from Janet Jackson to Cliff Richard), crafted an exquisite conversational album of pop gems the next year, Vision, for the Reunion label, that, sadly, went nowhere within Christian or pop circles. Similarly, Kathy Troccoli released the stunning Images in 1986, which seemed a prime candidate for crossover, but failed to reach even the success of her prior efforts within the Christian world, and made no dents outside of it. She would score a pop hit in 1991 with “Everything Changes,” but the success would only occur once. Another Grant collaborator, Michael W. Smith, would also achieve a singular pop hit in 1991.

The crossover conversation, however, would divide the Christian music audience. Lundy also told Billboard, “The audience has forever split. We have artists who have an evangelical slant and we have artists who work strictly within the body of Christ. We didn’t split, the audience did.” Lundy’s observation was truer than he may have realized. The audience did indeed split, but in the wake of the 1987 Jim Bakker scandal, the market withdrew as well and catered, almost exclusively, to listeners within the Christian bubble. Over the decade that would follow, artists with their eye on pursuing the shared humanity that Grant sought out, found themselves further and further outside of Christian music framework. Leslie Phillips, who reigned with Grant and Sandi Patty as the three best-selling female vocalists in CCM, departed in 1987 for a deal with Virgin Records and a new career as Sam Phillips that promised creative freedom. Russ Taff would pursue a country career for a period in the 1990s and others would become songwriters in pop and country.

While Unguarded is certainly heralded as a classic today, its relevance seems overshadowed by the massive success of Grant’s 1991 Heart In Motion, in which she achieved what she’d set out to do in 1985. This, however, only increases the importance of studying Unguarded, the seedling that started it all. For many young people, like me, who grew up in the church and felt imprisoned by it, Unguarded was an invitation to our own humanity, permission to desire to know people who weren’t like us, who knew nothing of our world. It presented the idea that the world didn’t have to be conquered, but that we merely had to exist in it. If what we’d been told was life changing actually was, then our presence in and navigation through the world would make more of an impression than our dogma. That notion, also, however gave us permission to experience the full range of our own human experience, which includes doubt, fear, and not knowing. That, perhaps, was the real danger and gift of Unguarded.

The finale of the 2020 season of Have You Ever Heard…? featured my good friend Matt Nightingale and I discussing our experience and memories of this album. Here’s our conversation in case you didn’t catch it!

If you haven’t subscribed to God’s Music Is My Life, simply click here!

If you missed last week’s article, click here!

Seriously well done. One of the best discussions and deep dives into Amy and her music that I can remember and I’ve been a fan since Age to Age! Thank you both so much!

Very educational for me because as Amy was becoming known I was still collecting and following Reba Rambo who you have also spotlighted beautifully. I miss so much of Amy's early projects but have really loved her later works especially the work with her husband Vince G. Thanks for the great history Tim