Not Gonna Bow: An Outsider's Take on Russ Taff's 'Medals'

This classic CCM album was one of the top albums of 1985 and was perceived by most as an album full of fundamentalist anthems. But I heard it differently.

1985 was the pinnacle year of my childhood. In the fall of that year, I crossed the threshold from nine to ten years old. I had enjoyed a summer filled with music that was unlike anything I’d ever heard (translated: been allowed to listen to) before. Between Tramaine Hawkins’ “Fall Down,” which scandalized the saints when it topped Billboard’s Dance Charts, Amy Grant’s Unguarded, Kathy Troccoli’s R&B-ish Heart & Soul and Sheila Walsh’s Don’t Hide Your Heart, it seemed to me that both gospel and CCM artists were defying traditionalists and figuring out how to appeal to an audience outside of the church. I played these albums in my grandparents’ living room, much to their chagrin. Over and over, they articulated that they didn’t understand what any of these albums had to do with God or how it was any different than the “secular” music I wasn’t allowed to listen to.

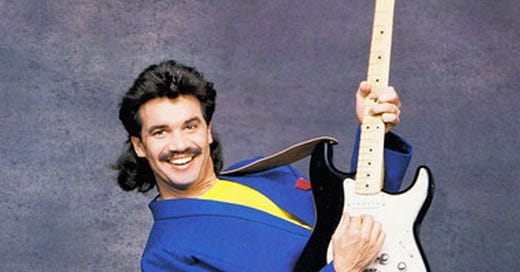

But there was one album they tolerated with a little less frustration: Russ Taff’s Medals.

Yes. They hated the guitars, the drums and Tata Vega’s scorching step out on “Rock Solid,” but they liked his ballads and that they could, at least, “understand what he’s saying.”

Medals is a tricky album to discuss in 2022. On the surface, to many, it reads as an album full of fundamentalist anthems like “Not Gonna Bow,” “Rock Solid,” and the title track. I would never even attempt to argue that the bulk of his audience didn’t hear it that way. But this album never read that way to me, despite its unprecedented success on Christian radio and the lasting impact it had on Russ’ career. As a church kid, songs like “Not Gonna Bow” and “Rock Solid” felt much more like they were about not letting intra-communal pressure in the church world melt down one’s individuality.

The ballads and mid-tempo tunes, like “I’m Not Alone,” “God Only Knows,” and “Here I Am” reflected an outsider-ness that spoke to the pressure of perfectionism in faith communities that created secrets, facades which hindered intimacy and vulnerability. “God only knows what doesn’t show, what you refuse to share. I’m not casting stones, I just wonder what you are holding in,” Russ sang, seemingly singing to himself and the listener. As a little gay boy in the church, I certainly held knowledge of myself that I could not safely share with anyone. Medals made me feel seen and safe.

As I watched The 700 Club and other Christian news shows rage about the National Endowment of the Arts funding alleged pornography (Robert Mappelthorpe’s work) and declaring AIDS as God’s divine judgement on homosexuals, I heard Medals affirming my identity, not detracting from it. I saw the rigid, fundamentalist messaging emerging from the church as one of the things I should not bow to. I did not have a life outside of the church, so when Russ sang “All Bobby wanted was just to fit in/To be accepted he must act like them/He said no,” I heard it completely differently than my peers. Why? Well, I was perceived as effeminate and continually being told to be “more like a man.” This was the peer pressure I was enduring. Manhood, toxic masculinity and Christian nationalism were idols I saw the people in my world worshiping. “Not Gonna Bow'' encouraged me to be fully me.

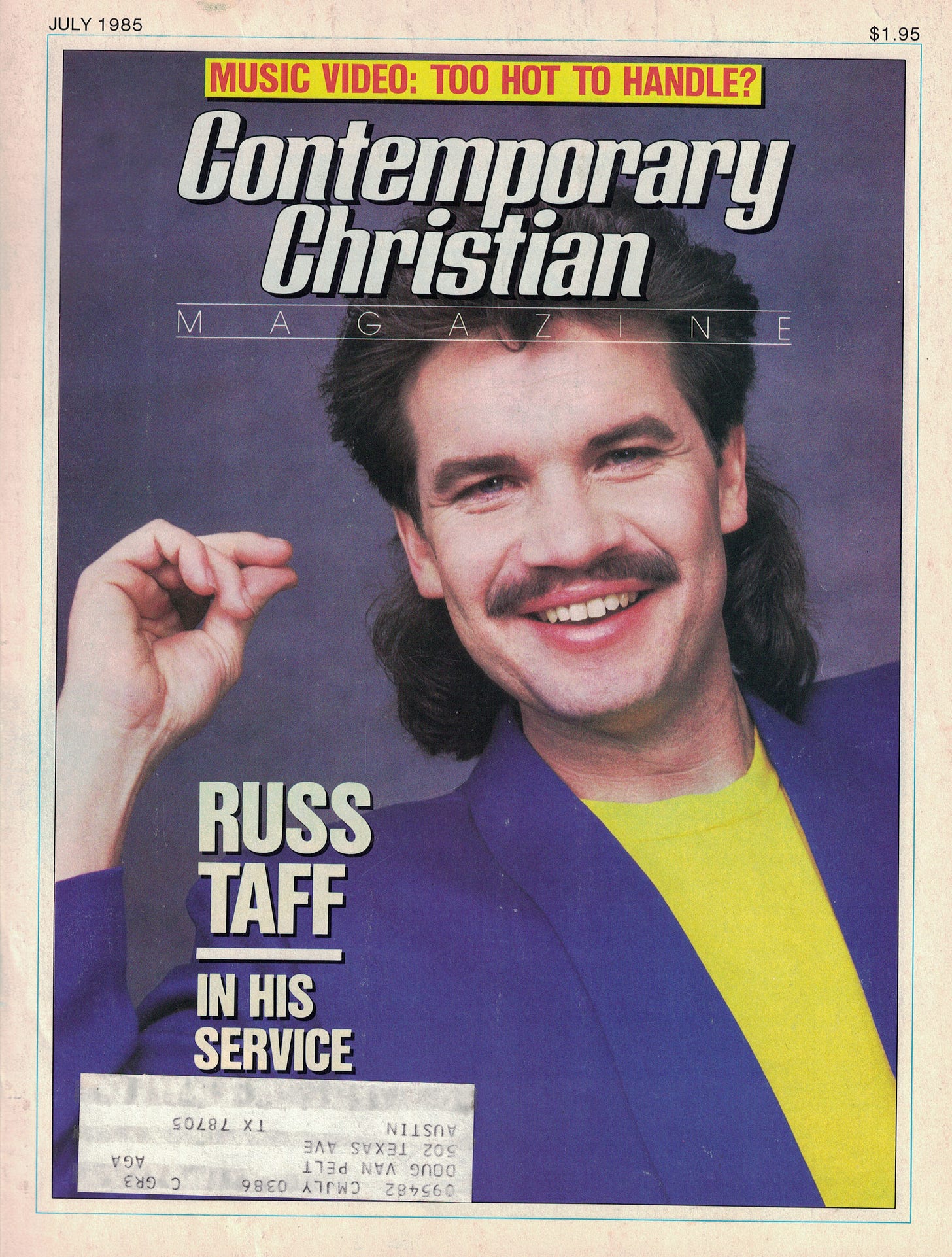

While Medals was indeed faith-filled, it was also accessible. Written at the height of the first wave of CCM crossover, there was a lot of conversation in Christian music circles about “selling out” in exchange for mainstream success. In a 1985 interview with Contemporary Christian Magazine, Russ and Tori discussed their own grappling with this discourse while making Medals. Tori told them,

“We’ve developed a real horror of taking a real hip track and trying to artificially cram the name of Jesus into the lyric whether it fits or not…There came a time on the song ‘I’m Not Alone’ when we were worried that musically it was too secular sounding. Finally, we realized it didn’t sound like anything. It was just a good track. Believe it or not, that was a difficult understanding to come to.”

That fall, Russ came to St. Petersburg, Florida for a concert at the Bayfront Center (with Farrell and Farrell as his opening act). My mother worked two jobs, so ticketed concerts were a privilege. We had just broken the bank to see Amy Grant on the Unguarded tour a month or so prior (to the tune of $15 a ticket), so when I begged to go see Russ I was met with an immediate no. The good news was that Russ was doing a record signing earlier in the day at Uncle Al’s United In Spirit bookstore, so my grandparents agreed to take me after school.

The line was long, but Russ did get to sign my beloved copy of Medals (the line was so long some were not so lucky). Just as I stepped out of the line, a man in paint-stained overalls walked up to me with two tickets for the concert and said that he felt like I was supposed to have them. My mother, bless her, got home from her hour-long commute from Tampa back to St. Petersburg, changed clothes, and got right back in the car to take me to the concert.

What I experienced that night has stayed with me over the course of the thirty-seven years since. Watching and hearing Russ Taff sing, particularly in that era, was to have the experience of witnessing someone doing their damndest to lay it all out on the altar. While, yes, this was a rock and roll show and there were the pulsing, crowd-engaging moments on Russ’ anthemic cuts like the aforementioned “Bow” and “Rock Solid,” the ballads were the space in which the atmosphere took on a different energy.

If memory serves correctly, it was towards the end of “Here I Am,” that Russ gave vent to the spirit. “Take this lonely heart of mine,” he ad-libs on the recording and, in my mind, he probably sang something similar that evening. He fell to his knees as the band continued to play the song’s vamp and began to weep. Just a few years later after joining the Black Fire-Baptized church, I’d identify this place, this feeling, as being in the mist. This may have been the first time I was there. I’ve had experiences that proved to me that there are times that we walk between worlds—the natural world and the Other world—and this was one of them.

A voice in the audience rose over the music, speaking in tongues. In my grandparents’ church, we recognized this as someone delivering a “message” in their “spiritual language.” I was wide-eyed. I’d never seen anything like this happen outside of my grandparents' church, let alone in a concert hall—but I’d also never felt what I was feeling in this moment in my grandparents’ church either. Unbeknownst to me, this concert was the beginning of my formulation of Pentecostal Humanism, the idea of what can happen, what we can co-create, when two or three people touch and agree, when we can “see” and “feel” one another from the purest place we can find within ourselves. It is ecstatic and healing—and we make it together.

Years later, Russ would reveal in his memoir, co-written with his wife Tori, that in this period of his career, he was struggling with debilitating alcoholism, driven by unresolved childhood trauma.

“I had no tools. I didn’t know why this was happening. I went through a period of time thinking ‘Am I demon possessed? I’m asking for help and I’m not getting anything. He’s not taking away this desire.’ That’s what I thought healing would look like–the desire to drink would just magically go away, along with the anxiety and negative voices…but I didn’t really understand the pathology of depression. I wish I would’ve known sooner, but I’m thankful that I do now. Antidepressants don’t always completely fix the problem, but they can help treat it,” Russ wrote in his memoir, I Still Believe.

Knowing this now, I look back at that night through very different eyes as I grapple with the intertwining nature of psychic pain and the quest for spiritual transcendence. The reality is that when the theology at one’s core encourages introspection, the quest for and experience of transcendence can be utilized as a means of facing and navigating the pain–not escaping or avoiding it.

In the years that followed, Russ wrote and sang his way through that quandary. None of the albums that followed Medals spoke with the same kind of certainty that made it such a poster-child for fundamentalism. Even before the Jim Bakker scandal of 1987 shook Christendom, the artists of that world were feeling the winds of change. Leslie Phillips’ opus The Turning, released in the spring of that year but recorded in 1986, indicated that the opulence, arrogance and dogma of a consumer-driven faith was wearing thin. Sessions for the self-titled Russ Taff album began in January of 1987 and continued through that unforgettable year which exposed the inner-workings of televangelism and, in many ways, the church at large. Russ Taff bemoaned in the album’s Dave Perkins-composed opener, “Shake,” “great big men with ego kingdoms in mind/tryin’ to tell me how to spend my money and time,” and urged its listeners in “Walk Between the Lines” to consider a more practical faith, one lived a bit more thoughtfully: “walk between the lines/finding deeper finds/my heart is hidden deep within the lines.”

1989’s The Way Home achieves and boldly articulates some of the more subdued messages in Medals. The album’s closer, “Table In The Wilderness,” co-written by Russ, Darrell Brown, and David Batteau, speaks of a table that has a place for all, “where the blind can see and the poor possess, where the weak are strong and the weary rest.” The album as a whole centers a reliance on both humanity and the spirit–not fearing the world, but sojourning with and undergirding our companions: “It’s a long road, but we can help each other.”

I asked Tori Taff, Russ’ collaborator and wife, to join me for a conversation specifically about Medals, but we couldn’t help but delve into their broader body of work in the conversation. Tori is an under-celebrated talent whose pen played a major part in birthing these innovative songs that have been a companion and comfort to many of us over the last four decades. I raise Medals as an album that could and should be listened to more deeply as a means of re-contextualizing and re-claiming language that has, in the years since, been weaponized by the powerful gatekeepers and influencers in evangelical settings.

You can watch or listen to our conversation below!

I love how you weave your own stories into the stories. You wrote: "Pentecostal Humanism, the idea of what can happen, what we can co-create, when two or three people touch and agree, when we can “see” and “feel” one another from the purest place we can find within ourselves. It is ecstatic and healing—and we make it together." Amen. Love the interview with Tori Taff!

This is awesome Tim. I’m glad you got to read their book (which I was honored to help them write!)... and chat with fabulous Tori. ❤️ big love to you.