In 2011, I abandoned my attempt at “making it” in New York City as a performer. It had been a rough five years. In 2007, I trashed the little career I’d been building in Nashville when I, after much scrutiny and inquisition, came out as a gay man. And I came out swinging. Let’s just say that in my attempt to walk in my truth, I did a lot more bridge burning than bridge building. Looking back on it at (almost) forty-six years old, I think “Oh Tim. You could have done that so much differently,” but that isn’t what happened. I moved to New York and did a run of sold-out shows in small venues, but never stopped to deal with the emotional upheaval I’d experienced in Nashville nor stopped to treat the new wounds I was incurring in New York.

In my last year in the city, I felt my body losing steam. After every show, I’d develop a throat infection. Every step felt like it was getting harder. I attributed it to my weight, the miles that I walked daily to the bus, subway and the distance to my job. “I’m just not built for New York,” I thought. But when I moved upstate onto a gorgeous property in the woods, found a job with an interfaith press, and began a new, quieter chapter of life, my body wasn’t rebounding. At the end of my first year there, I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia. My doctor put me on a particular medication that she thought would help, but within days, I was in the hospital, near death. It’s a much longer story that I won’t detail here, but it was that near death experience that put me in bed for the first five months of 2012. It was the hardest, most wonderful experience I’ve ever had.

When I was released from the hospital and prescribed an incredibly high dosage of prednisone, I spent a large part of my time between the worlds: too wired to sleep, in too much pain to be fully coherent. One sleepless night, I found a documentary on Amazon Prime called Radical Harmonies. The thumbnail on the screen was too small for me to really see, the description of the film very vague, but a little voice, the one that often has more foresight than me, told me to watch it.

Radical Harmonies was an introduction to a world I knew little about, but should have known all about. The film documents the incredible musical culture built by lesbian feminists in the early 1970s out of the consciousness-raising work done in small gatherings in the living rooms of women’s homes around the country. Developed outside of the confines of the mainstream version of feminism (where lesbians were seen as “the lavender menace”), Women’s Music pioneers like Meg Christian, Alix Dobkin, Cris Williamson, Margie Adam, Sweet Honey in the Rock, Gwen Avery, Linda Tillery, Teresa Trull, Mary Watkins, and Holly Near created a body of work from a unique perspective and with a distinct purpose.

In her book An Army of Lovers: Women’s Music of the 70’s and 80’s, author Jamie Anderson quotes Olivia Records co-founder, Judy Dlugacz, defining it this way to Bitch, “(Women’s music) simply reflects the consciousness of the audience. It doesn’t have anything to do with a musical style.” Radical Harmonies highlights the diversity of these artist’s work, but the commonality in their stories was the idea of making music outside of the patriarchal gaze, without consideration of the mainstream. Besides Sweet Honey in the Rock, I knew nothing of this! How was that possible?

In the recesses of my mind I had memories of my mother’s burgeoning feminism in my childhood. We frequented a Women’s bookstore in our area, Brigid’s. She had cassettes by Sweet Honey in the Rock and Sapphire The Uppity Blues Women and was a member of the local NOW chapter (trust me, I was the only kid in my Southern Baptist high school who wore an “I Believe Anita” button during Clarence Thomas’ confirmation hearing), but I was too immersed in my Sandra Crouch and Hawkins Family tapes to really absorb this piece of my mother’s world. My discovery of women’s music, however, proves that everything always comes full circle.

It was Meg Christian’s music that I was immediately drawn to as I watched the documentary. The opening strains of “Valentine Song'' shot straight to my heartcenter. This song about a new relationship, a new love that has become home, washed over me, became part of me as soon as I heard it. I checked iTunes and Amazon and found that nothing by Meg was available digitally. I ripped what I could from YouTube and began furiously scouring eBay (and when I got back on my feet, crate digging) for vinyl. Meg (and the other women I learned about in the film) became a part of my healing soundtrack.

The music awakened me intellectually. It made me take stock of, not only what I’d experienced since coming out, but, the framework I’d been unsuccessfully living in my entire life. That self-evaluation became the best therapy I’ve ever had. I began reading lesbian feminist poets and theorists: Pat Parker, Monique Wittig, Audre Lord, in particular, and I looked for as many of the “little books” and pamphlets that had been published by woman-owned presses at the time. I began looking at the ways I had felt forced to participate in gender performance, the ways masculinity had risen up against anyone or anything it perceived as the feminine. This, then, made me look at, in my own life, the ways the church had been used as a weapon of mass destruction against the feminine. While in the 70s these were the conversations women were having in consciousness-raising groups, I was having them all by myself in my little cabin in upstate New York.

Meg Christian, for me, was the central figure in all of this. I was and am intrigued by the woman who should be getting lifetime achievement awards and whose albums should be receiving vinyl reissues and praise from the current crop of singer/songwriters as an unsung hero. There are documentaries with other people relaying the stories of her envisioning and coining the term ‘Women’s Music’ and thoroughly interrogating what that meant and what it could be. We know that she and a collective of women would create the now legendary Olivia Records (Meg is quoted in a 1976 interview saying “We want to learn decent jobs and skills, to free ourselves from having to do shit work all the time.”) and that the music they recorded and released (with exclusively women musicians, engineers and staff) would mobilize women and form the foundation of a cultural movement. I’ve heard people describe what her early concerts felt like and wish they existed on film.

But, for the most part, Meg’s albums and interviews, which stopped in 1984, are what we have to hear the story from her perspective.

Her first two albums, I Know You Know (1974) (which would sell over 70,000 copies—no small feat for an independent label without distribution access to the “major” music sellers) and Face The Music (1976), show the breadth of her musicality, lived experience and intense curiosity to know and be more.

I Know You Know dealt with coming out, the fraughtness of that experience with family, the long-term, internal, emotional price of repression and the overarching weight of oppression. The album was, for many of the women who found it, a revelation. While hints of lesbian identity had to be searched out in pop music (Laura Nyro’s “Emmie” would be one of the most obvious), I Know You Know was clear in who was being sung to. In an early interview with Off Our Backs, Meg said,

“Even though all of my songs aren’t specifically political, they are sung by a woman to other women, and, as such, they can mean different things. It gives women a chance to enjoy or identify with a lot of songs they wouldn’t normally relate to. That’s a strengthening and happy experience, something we don’t have very often. Also, I can preach in certain ways that would never get through if I were giving a political tirade.”

Her second recording, Face the Music, was a bit like a travelogue of what happens after coming out and embracing feminism: the interrogation of unconscious racism, the quest for and embrace of community, and, in many ways, the awe and embrace of feminine energy. In their review of Face the Music, The Lesbian Tide would say that “It’s the power in ourselves and our lesbian lives that we hear in women’s music and that makes us enthusiastically respect our artists. Face the Music is a celebration of this marvelous woman energy that we all share with one another.”

She told Pointblank Times in 1976,

“I try to present songs that make women feel good about themselves for the first time, or make women start thinking about feminism politically, or make a woman want to deal with loving other women, or putting all her different kinds of energies into women, or perhaps dealing with the fact that lesbianism is political. Lesbianism is, for me, the crucial political step in women supporting one another and making a revolution.”

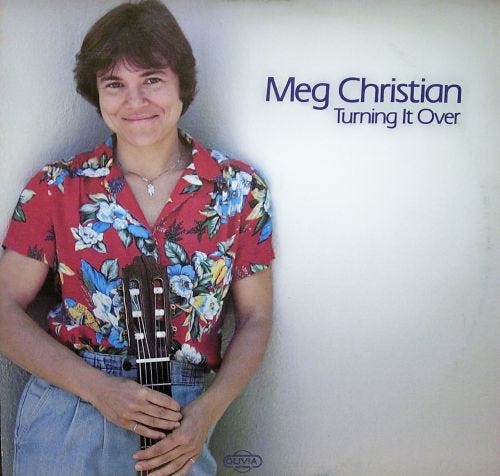

It’s Meg’s third album, Turning It Over, released some four years after Face the Music that, to me, stands as the most vital. It marks a turning point. From the album’s opening strands of the title song, it’s clear that something has changed.

Summer is fading

The wind’s a little cold

I feel the seasons as they’re turning

in my soul

Meg had turned to the Spirit, as she sang in the album’s title track, “to the one who can run it without any help from me.” The songs on the album’s first side all point directly to this expansion in her world view. “There’s a Light,” written by Julie Homi (recorded a year prior by Olivia artist Teresa Trull on her Let It Be Known album), is an ode to the divine feminine. “Restless,” a lament of the rigors of a musician’s road life, also points to the difficulties of holding center and staying in the moment (“This too shall pass, I know, I know, but tell me, please why is it so, that all the best pass so fast and the lousy roll so slow”).

These changes may seem minor, but there was a distinct shift in both the message and music. Meg had spent the prior decade on the road, as an evangelist for feminism. Her concerts had created both a physical and emotional space for women, fearful of losing their livelihoods and families, where they could find one another as a source of validation and emotional support. Olivia co-founder Ginny Berson writes in her memoir, Olivia On The Road: A Radical Experiment in Women’s Music, “Sometimes the response was a bit overwhelming. I remember a concert in Boston, in 1975, in a large hall that might have been on the campus of Boston University. Meg walked out onto the stage and was literally knocked backwards by the waves of energy that the audience sent her way.”

This album was not a mobilizer in the same sense. Meg was not serving as a revivalist anymore. She was directing people to look inside. In the years between albums, she’d sought treatment for alcoholism. “I would go out there and work, and people would stand up and cheer, and I was dying inside from old self-hate that never got healed. I went straight from political analysis to political action and didn’t give myself time to sew up the wounds, and so I stuffed it all [inside] and was drinking and drinking and pretending that I was fine, just fine, and thinking I was the only one.”

“There’s a lot of leftist criticism of women’s culture that says that we talk about the personal too much.” she told writer Mary Pollack in 1982. “Of course, I think that’s what makes feminism unique as a political idea. Feminism is an internal as well as an external politic. We’re talking about changing inside, changing the way that you and I sit on this sofa and talk, the kind of mutual respect we share, power-sharing, a sense of equality as we talk, a sense of compassion about the world and its inhabitants.”

While many saw Turning It Over as a ideological departure, it was simply a continuation on the feminist path. The next phase. The notion of a collective “we” seems to have expanded. Meg’s lyrics and messaging in interviews seems to be urging her followers to tend to their individual selves, distinct from the “we” that some might have previously interpreted as a monolithic way of being and doing feminism.

She told The Advocate in 1981,

“We all have such ideals in the women’s movement and the gay movement about how we want ourselves to be as individuals—strong and free and flexible and able to utilize all our talents. We have ideals about the society we want to create. But I don’t think we’ve created a lot of structures for dealing with all the fear and the pain that still underlie that. We need to realize what we have not done for one another, the kind of nurturing and healing structures we have not created for one another yet.”

She wasn’t simply positing modes of self-care for the culture, she was also suggesting that, for her, the lesbian separatism she’d advocated for and participated in for essential reasons was now phasing out as well. “There are some who only want to perform for lesbians. We are that diverse. I absolutely respect where every woman wants to be. But for me, I see more coalition stuff going on.” She was echoing words that Bernice Johnson Reagon had spoken earlier that year at the West Coast Women’s Music Festival:

“We’ve pretty much come to the end of a time when you can have a space that is ‘yours only’—just for the people you want to be there. Even when we have our ‘women’s only’ festivals, there is no such thing. The fault is not necessarily with the organizers of the gathering. To a large extent it’s just because we have finished with that kind of isolating.”

Turning It Over is distinct in Meg’s catalog because that sense is present. Her path had expanded beyond what many of her long-term listeners had pursued. She told a reporter in 1984, in one of her last interviews,

“There are songs (I do) about a deeper kind of freedom that everybody is longing for in their lives. At my shows now, I get everyone from grandmothers to little kids, and that’s pretty amazing. There are certainly more men who come to hear me now, as well as women who I would not identify as being a part of the ongoing core of the women’s community. Feminism deals with respect, being nurturing, making your own choices and making changes on a one-to-one basis. Women’s music is reflecting this sense of change.”

Christian and Reagon’s sentiments point to a flexibility that they infer is inherent to feminism (before it was referred to with an “s” at the end)—a willingness to change one’s methods as one’s understanding expands. Olivia Records, in particular, would face a lot of criticism from women’s culture for their inclusion and methods that were always negotiating with an audience that was, in many ways, exhaling in the presence of the safety that women’s culture was providing them.

The closing song on Turning It Over, “I Wish You Well,” could be read, in one sense, as a farewell from Meg herself (even though she wouldn’t actually retire from Women’s Music for another three years), but also a prophetic foretelling of the end of an era. “Please make your way with care, there’s so much danger out there. So many dead and dying ends, my friends. Go and fight what’s holding you down, but keep your armor sound. I never want to meet a martyr again! I wish us well,” she sang.

I raise Meg’s work this week, following last week’s feature on contemporary Christian music artist Leslie Phillips, because there’s a thread that connects them. Both emerged as part of musical cultures that were genres in an ideological sense—not because of a singular sound or style. Both mobilized audiences around those themes, but had spiritual and philosophical evolutions that left them to make unanticipated choices about their futures and changed the trajectory of their careers as commercial artists. Meg explained to the San Diego Union-Tribune, “I’m starting to make deeper, more spiritual connections that apply to more than one group of people.”

Both “left” the worlds they had been a part of creating. While Leslie rebirthed as Sam Phillips and went on to create an entirely new body of work under that moniker for Virgin Records, Meg would record a live album with Cris Williamson (1983’s Live at Carnegie Hall) and one more solo album for Olivia Records (1984’s From The Heart) before moving to an ashram in upstate New York and becoming Shambhavi. As a student of Guruyami Chidvilasananda, she has recorded a series of albums inspired by her spiritual path that were not released through commercial channels. She stopped performing full-time in the eighties and makes select appearances on Olivia Travel’s cruises.

A 1989 Hot Wire article quotes Meg as saying,

“The teachers and heads of Siddha Yoga stress over and over again that the point is not to leave the world, but to learn to live in it. And not just be so caught up in the roller coaster ride that makes us all crazy and burned out and sick and angry, but rather to do what we came here to do to the fullest, most loving and powerful way we can do it.”

Her departure leaves me with a lot of food for thought. It expands the notion of what going out “into the world” can mean. We as both artists and listeners are programmed to “do what we love” and are taught to do that singular thing for the rest of our lives without much variance. My own physical and emotional crash forced me to re-evaluate that premise. My love and passion for music has remained, but both my pursuit and expression of that have taken different forms. Maybe that’s what “Turning It Over” really means--shape shifting, changing, expanding, becoming further integrated into oneself.

Last year, my husband, Ray Curenton, and I had a focused conversation about Meg’s Turning It Over as part of the Have You Ever Heard…? series. (When you’re done watching, be sure to subscribe to my YouTube channel!)

To subscribe to the weekly newsletter, click here.

Bravo, Tim! What an exceptionally well-written, well researched, and eloquent piece. Thank you for keeping the herstory and memories alive!❤️

The more I read these the more I see just how awesome and multi-faceted you are! May God's richest blessings always be upon your life! Continue to be imperfectly perfect you!