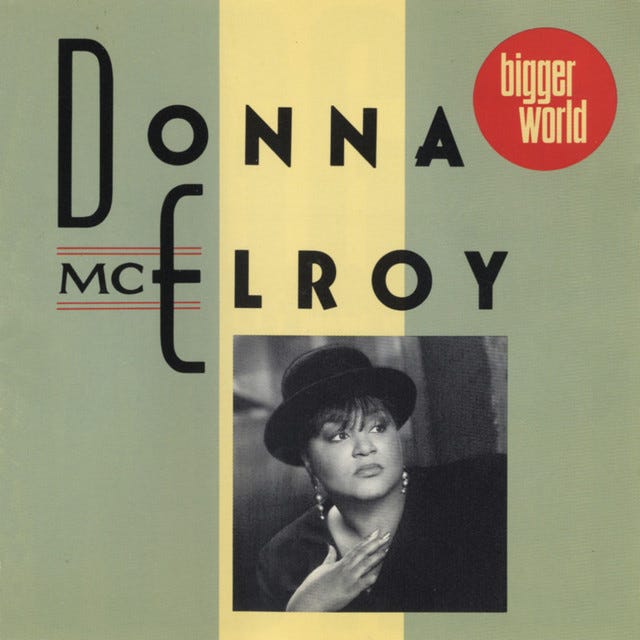

Her Way: Donna McElroy's Vision of a Bigger World

30 years later, McElroy reflects on an album that attempted conversations about the things that divide and (could) unite humanity.

When she was fifteen years old, Donna McElroy won a talent contest in Louisville, Kentucky, her hometown, singing Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.”

For what is a man, what has he got?

If not himself, then he has naught

To say the things he truly feels

And not the words of one who kneels

The record shows I took the blows

And did it my way

Over the next twenty years, she would build a career in music doing just that. You’ve heard her on albums by Garth Brooks, Reba McEntire, Millie Jackson, BeBe and CeCe Winans, Shirley Caesar, Kenny Rogers, Amy Grant and so many more, but you may not have known that in 1990, she began a solo career with the release of Bigger World. Just behind Take 6, she was the second artist signed to the then-new Warner Brothers Gospel imprint that would become known as Warner Alliance. Her music couldn't have stood any further apart from the messaging that was dominant on Christian radio at the time. A quick perusal of the songs and albums on the contemporary Christian chart of the time are a mix of Christian nationalism, end time dreams and scripture songs that reflect the messaging that was most popular with the consumers of Christian culture. But that summer, Bigger World attempted a different conversation about racism, inclusion and self-determination. Her way.

McElroy had come to Nashville from Louisville, Kentucky in 1973 to attend Fisk University. Her childhood was packed full of music. “On Sunday mornings, I was listening to my mother play Tennessee Ernie Ford, George Beverly Shea, Mahalia Jackson. My father was a jazz man. He had maybe 1,500 records in his collection and they were mostly my favorites: Ella Fitzgerald, Joe Williams, Carmen McRae, Sarah Vaughan, Nancy Wilson, Cannonball Adderley. When we would come home from church, we’d start listening to this fabulous jazz music and I was singing along, washing dishes. It was constantly in my brain. Music was always there.”

She recalls attending choir rehearsals as a child, watching as her mother, who she says was her vocal idol, directed. “I’d be in the back of the church with the babysitter singing along while they were singing and my mother would say something like ‘Oh altos! You can’t get that? A baby can do that! Donna!’ And she’d holler to the back of the church and I’d sing the part.” She spent her youth singing in church, local events and contests. After winning the Crusade for Children Talent Contest at Louiville’s WHAS-11, she was certain of her life’s course. “Nobody [at the station] had heard me sing before and this big voice came out of this little fat girl and it was all over. They placed a little crown on my head and I really saw that I could do this for a living.”

When she arrived at Fisk, she was a member of the famed Jubilee Singers and the Modern Black Mass Choir. “I couldn’t see myself totally being a classical singer, so [my voice teacher] and I had a constant conflict between us. She was trying to win me away from the world of Stevie Wonder, Roberta Flack, Natalie Cole and the Emotions. I wasn’t going to give that up!”

After she graduated in 1977, she began doing session work for several Nashville producers, including Moses Dillard and Jesse Boyce on disco projects, along with her childhood friend Vicki Hampton who had also moved to Nashville. They were the voices of the Saturday Night Band and the Constellation Orchestra, both produced by Dillard and Boyce, released on New York’s Prelude Records.

In 1979, she began doing session work for country artists like Kenny Rogers on his hit “You Decorated My Life,” continuing the path forged by Nashville’s Twenty-First Century Singers, bringing the gospel sound to country. “It was an interesting time because there were a lot of records that came out with our voices on them that changed the sound of Nashville music because the country artists really wanted to sing a little bit more meaty or soulful, more gospel, more roots-sounding music. They would hire me and Vicki [Hampton].” Producer Sanchez Harley recalls, “Donna would talk about her friend that she sang with back home and convinced her to come to Nashville. Donna and Vicki Hampton together had the most incredible blend!”

That year also marked her first sessions for CCM projects, including two Grammy winning albums, B. J. Thomas’ 1979 release You Gave Me Love and Debby Boone’s gospel debut With My Song in 1980. Her country and soul work for artists ranging from Millie Jackson to Reba McEntire increased as well. But in 1981, her career temporarily halted when she drove off a cliff on her way to a church service. She recalled in a 1990 interview, “I was out there on drugs. The time I grew up in was an experimental period. We reached out and searched all around for things to make us feel better.” The car accident occurred while she “was in the process of one of those little ‘trips’ that I had become accustomed to taking.” When she came awakened in the hospital, “I had to be told that I was a singer,” she recalls. The doctors were not “cooperative or supportive to my recovering,” she told Contemporary Christian Magazine. She says, “This was probably due to the fact that they said I came in riddled with all kinds of weird drugs; that I was acting crazy. To add to that, I was in shock, not knowing where I was.” She adds, however, that the experience helped her “key in on the most important thing in my life that God had blessed me with which was singing.”

Upon being released from the hospital, she briefly toured with country artist Crystal Gayle. When she returned to Nashville from the Gayle tour, she received a call from Dan Harrell and Mike Blanton who managed an up and coming singer named Amy Grant, who had just released her fourth studio album, Age to Age. They asked her to go on the road with Grant as a supporting vocalist. “It was not really spoken, but what they needed was a strong female voice and presence for this young girl to go out on the road and emulate vocally.”

The early days on the road with Grant were meager and far from glamorous. McElroy says, “When we first started out [touring]…we had only one bus and we’d be on that bus until we stopped somewhere…and rented a room for the girls and the guys. We would rent the room for like six hours…everybody would get a bath…whoever needed a nap would take a little nap in the room and get the land legs, then we’d climb back on the bus and go to the next gig.”

McElroy’s session work continued as well. She appeared on some of 1982 and 1983’s biggest CCM releases, including Kathy Troccoli’s Stubborn Love, Rick Cua’s Koo-ah, David Meece’s Count the Cost and Grant’s Grammy-winning EP Ageless Medley. “All of that time,” Donna reflects, “I was walking through the whole experience singing background with people, I was never looking at the artist side of things. We were doing what they called ‘head arrangements.’ Vicki and I would come in and we’d make up stuff.” McElroy received credit as a singer, but not an arranger, on the albums when they were released. “Because I didn’t know that I was supposed to be making extra change, I felt like that was enough. [I thought] ‘I got record credits…that’s something I can put on my resume.’”

“In the studio, Donna was the ideas person,” recalls Bob Bailey, who was, at the time, a CCM artist and session singer new to Nashville. “She was and is a brilliant mind in terms of the music itself. [She’d say], ‘Let’s do this arrangement,’ ‘Let’s flip this.’” The sheer volume and diversity of Donna’s session work is a testament to what she was bringing to the table. She says,

“I think my subconscious thing through my life was to get things done and to do things in spite of and to do things accompanying being a large woman. I felt like I didn’t want to look at what I wasn’t getting to do. I wanted to do as many things as I thought I could do if I was allowed. If you let me in, I’ll do it and I’ll make you shine.”

Between 1983 and 1985, Grant’s popularity increased significantly, resulting in Christian music’s long-awaited crossover possibility being realized with her 1985 release Unguarded.

“Amy had an aspiration similar to mine which was she didn’t necessarily want to only be known a Contemporary Christian artist. She wanted to be known as an artist who is a contemporary Christian. So you don’t just sing about Jesus on every song…You don’t just sing ‘Sing your praise to the Lord…come on everybody get up your hands and sing hallelujah.’ You sing about life in the hallelujah state of mind.”

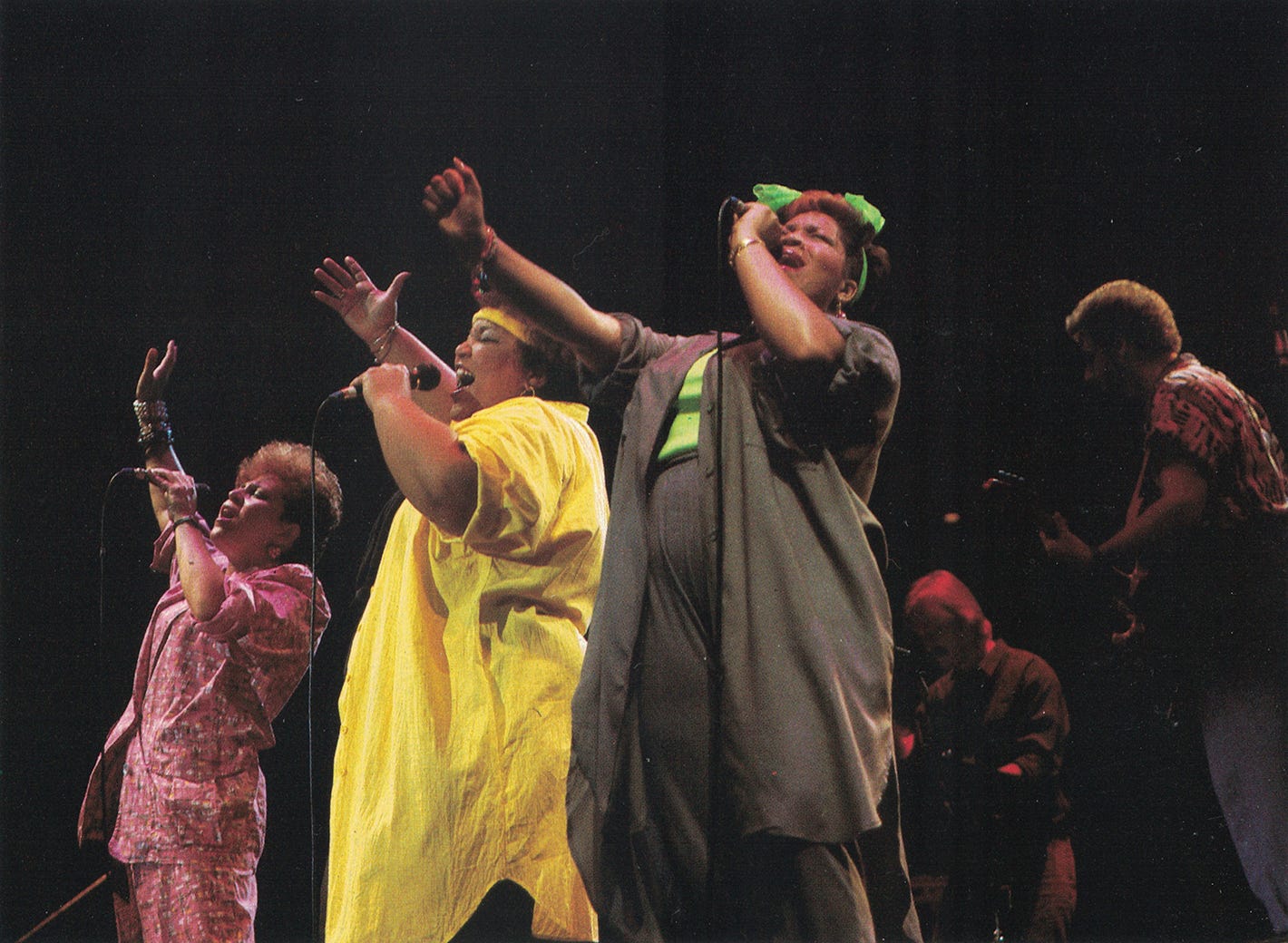

When the first single from Grant’s Unguarded hit #7 on Billboard’s Adult Contemporary chart and cracked the top 40 of the Hot 100, she became a bona fide star. In 1986, Grant tied with Whitney Houston as the top-grossing female act in terms of concert attendance. Donna, along with the other two background vocalists, Kim Fleming and Renee Garcia, were known as These Three on the Unguarded tour, and performed a set with Grant’s then-husband, Gary Chapman. “Singers Kim Fleming, Renee Garcia and Donna McElroy brought the crowd to a near-frenzy with their impassioned singing,” said a critic from the San Diego Union-Tribune. Donna reminisces, “Me and Gary and Amy together were a moneymaking brand. And then you add on Kim Fleming and Renee Garcia…[it’s] just like fabulous butteriness.” Grant would tell audiences, “I grew up stiff and white. Donna is teaching me [how to get] what’s in my heart to come out of my mouth.”

On the 1989 tour supporting Grant’s Lead Me On album, Donna returned and the press took notice. One critic wrote reviewing the Australian leg of the tour, “Donna McElroy stole the show. Given one song, a number with the great gospel chorus line ‘I’ve Got the Joy, Joy, Joy Down In My Heart,” she ripped through the timidity of the evening’s proceedings and showed that when it comes to popular liturgical music, a good gospel singer has all the answers.” When the tour passed through Baton Rouge, Louisiana, a critic also noted McElroy’s solo moment in the show: “When backup singer Donna McElroy soloed with her gripping Black gospel version of ‘I’ve Got the Joy’ it made me wish that Grant’s music would absorb some of McElroy’s solid sense of direction.”

After the 1989 tour ended, Donna was preparing for a concert at Fisk University’s chapel when she ran into Jim Ed Norman, a Warner Brothers executive she had worked with on country sessions.

“He said, ‘Why are you singing backgrounds? You should be an artist, you are fabulous.’” I went in and had my initial meeting with them and they asked me, ‘Who is your demographic?’ And I did not know what they were talking about…I had no demographic because my demographic as a background singer was these young white kids who were screaming at the top of their lungs for me down in front of the Amy Grant stage. But that was not my group. I was not going to be able to build a recording career off of those people, and I didn’t know that.”

With a deal on the table from Warner, she went to a management firm she knew for representation. “I go to the management and I said to them, ‘Would you help me sign this deal with Warner?’ and they said, ‘Warner! Are you kidding? Those are the most sin-driven people in the world. We don’t want anything to do with Warner.’ Now you’re getting in the politics of the industry and this is stuff that I didn’t know. I didn’t know ya’ll hated each other! I’m just trying to make my life connect. I’ve got a lot of loose ends here that I want to tie up into a nice little artistic package. I thought maybe I’d sign with Word [Records], but Word wasn’t looking for no African American, 300 pound 31-year-old woman! They were not looking for Donna McElroy.”

Donna signed with Warner and began work on the album that would become Bigger World with several different writers. The first of which was with Victor Caldwell. Caldwell’s musical palette was as far-reaching as McElroy’s. A lover of bands like the Bar-Kays and Earth, Wind & Fire, he was equally a student of jazz fusion. He and his brother, Cedric, had released As We Bop on MCA Records in 1988 as Caldwell Plus, which showcased their writing and production capabilities. He and Donna met for a writing session and immediately hit it off. "I gave her two tracks and she came back with the lyrics, the melody, the whole nine yards.”

When Donna took demoes of the first two songs to Jim Ed Norman at Warner, he enlisted Caldwell to produce the bulk of the album with McElroy. Her producer’s credit was a rarity in Contemporary Christian Music, as women were rarely at the helm of their own production. Caldwell says, “Just think of all the things she produced on the road, arranging the vocals, all the sessions she’d done. People were calling her because of her expertise. It’s not like she was stepping into new shoes. She was doing this anyways!” Bob Bailey, one of the vocalists McElroy called for the Bigger World sessions, agrees. “Donna is not only a great vocalist, but she has an affinity for the instrumentalists. All of that factored into her producer hat. She knew what she wanted to hear. She was able to express herself through the tracks...her way.”

Donna would also be paired with Trace Scarborough and Scott McLeod, who had just gotten a song placement on First Call’s God Is Good album. “We were pretty new writers at that point. We were just getting our legs and Donna came over to write with us.” She took the tracks they’d composed and returned a few weeks later. “We got back together and she showed us her ideas. She had the melody locked down for both songs.” When McElroy took the demos back to Norman at Warner, she suggested that Scarborough and McLeod produce the tunes as well.

But, there were differences that arose as others at Warner heard the material McElroy and her producers were creating.

“They kept trying to make me rewrite the lyrics…[to] make them more secular. They wanted them to cross over. [They would say] ‘The track is sounding really secular, but these lyrics are not going to make it.’ I said, ‘How do you know? Have you ever been in a Black club before? When is the last time you were in a Black club listening to any kind of music? You automatically assume that all we want to hear about is sex and having babies.’”

McElroy was certain that her album should be marketed to the Contemporary Christian market. “…I was so adamant with them in not necessarily making me a crossover artist. I wanted to be an artist who was a contemporary Christian, and I wanted my music to reflect my personality and who I was in the Lord, flaws and all…sometimes I would come up in there [the office] a little bit high and…anything might slip out of my mouth. And they weren’t ready for it.”

The culmination of the work was a tour de force of musical forms, ranging from traditional jazz to hip-hop to pop to soul. An established contemporary Christian label might never have allowed such a diverse album to have been made in the first place, but the creative freedom that Donna experienced was likely due to the fact that she was the second artist on the Warner Alliance roster and the division did not have a staff that was well versed in contemporary Christian or Black Music forms. “They had me all in their machine, but all these people had never developed anybody female, Black and non-country before, so they did not know what to do with me.”

Meanwhile, Christian music press loved the album. Contemporary Christian Music praised the album’s diversity and said “McElroy and Warner Alliance have succeeded in creating yet another fine album that will do well to evangelize in multi-markets. Why? Because this album is simply that good, that commercial and is what is currently ‘hot’ in the music world.” Cornerstone Magazine said that Bigger World was “soaring…punchy vocals, great lyrics, tunes for bustin’ a move” and “proves to be a top recording in an already stellar year of Gospel music.”

Other critics, however, were complimentary of Donna’s voice, but not the album’s direction. One critic suggested that “once McElroy decides on her direction, she’ll rise to the top. She’s very good, but this disc remains a paradox.” McElroy speaks to that criticism: “It was two or three different vocal personalities and they could not figure out ‘what is this woman doing?’ There’s no way to show a versatile multi-application of one voice. That is not going to happen in the record industry.”

At McElroy’s insistence, she shot a video for the first single, “Part of Me,” prior the album’s release. McElroy says this was opposite of how the Warner executives were used to working their country releases. “I kept trying to tell them…you’ve got the steps backwards. For Black music, you need to put the [single] out, then you go to the radio station…then the record comes out.”

“Part of Me,” the first song Caldwell and McElroy wrote for the project, proved to be a difficult first single—as it challenged the racism that McElroy had experienced in the world and in her working environment. “Part of Me,” which she dedicated “to the fighters of indifference and injustice everywhere,” was far from the colorblind-themed tunes about racism that CCM artists had written and celebrated in the past. McElroy put the responsibility for the problem and resolution in the hands of the oppressor.

I’ve been looking for a way, trying very hard to let you know my feelings/I’ve been looking for a chance to unearth some old resentments I’m concealing

Now, I’ve convinced you of my mind so you know there’s nothing I can’t understand/So if this quality you’re looking for and trying hard to find is the power of love, well it’s in your hands

Why you wanna hurt me the way you do?/Don’t you know, you’re a part of me

Why you wanna leave me with nowhere to go/Don’t you know, you’re a part of me

Black face, white face, we all bleed the same red blood/Light face, dark face, we should work for common good

‘Cause we can fight each other, leaving nothing more than a trace of our destruction/Or we can work for harmony and a little more love/And turn cold resentment into warm embrace

Why you turn away from the pain in my eyes/Don’t you know, you’re a part of me/I might not have what you have, but it’s time we realized/We’re in the world together

“Part of Me” attempted a conversation that McElroy says was “evidently too meaty…They wanted a little more fat. I had too much gristle.”

It’s impossible to not compare “Part of Me” to The Winans’ “It’s Time,” a massive hit on both mainstream R&B, CCM and gospel radio. The Winans were, in a sense, labelmates of McElroy, distributed to the Christian market by way of an agreement between Qwest Records and Warner Alliance. “It’s Time” called on diseases and natural disasters as a sign of the times and ultimately longed for the rapture as an escape, with Teddy Riley providing the only practical solution: “What we need is a little more love.” The contagious “We are his people, we can do it” hook ultimately never led anyone to a concrete idea of what the “it” [the action] might be. “Part of Me,” on the other hand, didn’t depend on the rapture for an escape. It was grounded in the here and now, leaning away from a performative righteousness/right-ness, and into the hard conversations that divide humanity. While “It’s Time” was seemingly everywhere, “Part of Me” couldn’t find a landing place. It seems that the clarity of “Part of Me” made it a non-starter. The lyric lays out the problem, its consequences and a course of action. Thirty years later, it seems just as appropriate and spot-on as it did then.

“The sounds of my voice were so aggressive and that was just not going to happen in Contemporary Christian Music. So they [Warner] decided to call this record ‘urban contemporary Christian.’ In other words, she’s Black.” Donna found herself in the boundary line between the Contemporary Christian, the Black gospel and the mainstream music worlds. For CCM radio, she was viewed as too Black; in the Black gospel world too contemporary and in the mainstream too Christian.

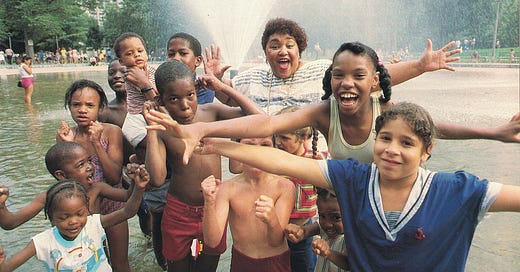

The video itself elucidates McElroy’s vision and the reasons it had difficulty finding a home. “Part of Me” maximizes the potential of who a contemporary Christian might be, what they might look like and how they could express themselves. For a market that was bent on both covering the body and not moving it, “Part of Me” had to have been a shock—not because it actually was shocking, but because it contradicted the ways Christian artists presented their music. In addition to the inclusion of dancing, the dancers wore what the Christian audience would have considered “revealing” clothing. One dancer vogues one minute into the video, invoking Black, gay ballroom culture, making this video an even bolder statement. Further contradicting the messaging of “It’s Time,” “Part of Me” reflects the world to the audience rather than rejecting it. She told The Tennessean that year, “I was on the road with Amy and I missed seeing Black kids and the dance crowd, which is where I wanted to take the message.”

At the center of Bigger World was Donna’s Mervyn Warren-produced take on Duke Ellington’s “Come Sunday” (which Mahalia Jackson recorded with Ellington in 1958), a prayer asking God to “look down and see my people through.” For some, “Come Sunday” seemed an odd inclusion as a traditional jazz tune on a contemporary R&B album, but it wasn’t when considered in context with Donna’s musical lexicon—and it was not out of step with what other artists like Teena Marie, Patti Austin and Angela Bofill had done throughout their careers through the eighties.

Warner pushed three more singles, the album’s title track, “Undoused Fire,” and “Unconditional Love,” with the latter making it to the #7 position on the Contemporary Christian Adult Contemporary singles chart. Chris Hauser, who came to Warner Alliance in late 1990 to take over the label’s radio promotions, suggests that Donna also suffered from the label’s lack of infrastructure at the time that her album was released. They did not have an in-house radio promotions staff when her singles were being pushed. Within a year of Bigger World’s release, the label would have a larger promotional staff, an A&R department, and additional senior staff.

Bigger World charted on Billboard’s Top Gospel Albums and earned Donna a nomination for Best New Artist at the 22nd Annual Dove Awards. The album track, “Come Sunday,” a cover of Duke Ellington’s composition originally recorded with Mahalia Jackson, was nominated for a Grammy in the category of Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying a Vocal.

Despite the album’s critical acclaim, the experience came at a high price for Donna. She had come off the road and stopped doing sessions to focus on building her identity as a solo artist, which significantly reduced her income. “I was demanding that they [the label] pay me something for my time. You can’t just get me off the road and have me sitting around. You’re taking me away from my means of employment trying to decide what you want to do with this voice.” Ultimately, Donna made the hard decision. “I spent two years thrashing around trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my recording existence…and realized ‘Hey…maybe I’m not a recording artist’ and I asked Jim Ed to release me.” He complied, and she says he apologized for the experience. “When I walked away from Warner…I was devastated, but I was glad at the same time…I was just so relieved that I didn’t have to go in and act like I wasn’t pissed anymore.” In reflection, she says, “I wanted my music to reflect my personality and who I was in the Lord, flaws and all. They weren’t ready for it.”

The following year, she returned to session work and would sing backgrounds on some of 1991’s biggest releases: BeBe and CeCe Winans’ blockbuster “Addictive Love,” Michael English’s explosive debut album, Vanessa Williams’ Comfort Zone, Amy Grant’s Heart in Motion, Carman, Commissioned & Christ Church Choir’s collaboration Shakin’ the House and Rich Mullins’ The World As Best I Remember It, Volume 1. She won a Dove Award in 1994 for her contribution to Song from the Loft, a multi-artist project produced by Gary Chapman.

Bigger World remained alive and moved in mysterious ways, however. A professor at Berklee College of Music gave his class an assignment, asking them to bring in an album that they wanted theirs to sound like. A set of twins brought Bigger World. The professor listened to the album and asked Donna to come and do a clinic on songwriting. In 1995, Donna moved to Boston and became a Professor of Voice at Berklee, where she remained for twenty-five years. She has released three independent albums and two DVDs. Bigger World continues to be available digitally. “…I didn’t know who I was when I left Nashville. It’s taken me coming here and learning who I was and how much I know.”

Special thanks to Donna, Bob Bailey, Victor Caldwell, Trace Scarborough and Chris Hauser for sharing their memories and experiences with Bigger World with me.

Great job, Tim! Can't wait to read what you do on Bob Bailey!