Reflections on the Music & Theology of Sheila Walsh's 'War of Love'

Revisiting this groundbreaking Grammy nominated album from 1983 and what it can say to listeners in 2023.

The eighties were an intense decade. In 1984, I was in the fourth grade attending a Southern Baptist school, seemingly inundated by a lot of rules and regulations. The boys' hair was measured regularly to make sure it wasn’t touching our collars, girls’ skirts were measured to make sure they weren’t “too far” above their knees, and we signed contracts at the beginning of the school year that we would abstain from things like rock music and movies.

In reality, most of my classmates did not abide by these stipulations. Because of that, I learned about artists like Madonna and Duran Duran from my worldly classmates that I was secretly jealous of. I was, as a preacher’s kid, forbidden from listening to this music (although my mother did, thankfully, sneak us off to movies). My only context for the music my classmates raved about came to me in flickers when I would covertly glide by MTV and VH-1 while clicking our remote control to one of the three Christian television stations that played non-stop in our home. I loved the fashions of the eighties: spandex pants with oversized duster jackets, Converse sneakers, jelly bracelets and spiked hair and I wished we were allowed to be a part of those trends at school. But we were not.

Around that time, I saw a British CCM artist named Sheila Walsh on one of the Christian music video programs I watched. She’d made a video for a song called “Mystery” that seemed a little closer to what my friends were watching than, say, Silverwind’s “A Song In The Night” or Tami Gunden’s “Then He Comes.” I knew getting Sheila’s music in my house would be a challenge. She didn’t say “Jesus” in the song and that probably wouldn’t fly, but I started asking for her album War Of Love (which “Mystery” came from) anyways, despite her leather jacket. They finally relented and I realized quickly that certain songs had to be played lower than others–electric guitars and synthesizers also set off my grandparents alarms–but Sheila became a favorite of mine.

War of Love was a state of the art pop album, co-produced by British pop icon Cliff Richard and Craig Pruess, filled with well-crafted pop tunes like “Mystery” and “Sunset Skies,” and theatrical new-wave influenced tracks like “Sleepwalking’” and “Private Life,” that gave Sheila’s operatic soprano (compared to Julie Andrews far too many times) some crunch. Graham Kendrick’s songwriting (of later “Shine Jesus Shine” fame) brilliantly made spiritual matters palatable without regurgitating clichés or Christian lingo that would make the album incomprehensible to the unchurched audience Walsh was clearly aiming for. Some of the stories on the album took place in England, others were about particular kinds of people, places and experiences and I loved traveling where the songs went. We were a deeply fundamentalist home and we lived by The Word–we didn’t talk about our feelings. Sheila’s songs did and that drew me in.

I learned years later that the album was released in England as Drifting, the title drawn from a love song she’d recorded with Cliff Richard that they’d hoped would introduce Sheila to the pop market, three years before Amy Grant would record a similar kind of song with Peter Cetera, “The Next Time I Fall.” Sparrow Records replaced “Drifting” on the American release of the album by a Christian radio-ready Christmas song, “Star Song.” That the American CCM market was shielded from “Drifting” makes clear just how forward thinking Walsh and her management were. She told Billboard’s Bob Darden in 1984, “In some ways, I think the English have a healthier attitude about Christian performers. In the U.S., if you become a Christian, you have to leave your secular career altogether. I think that is narrow minded. If I was a Christian butcher, does that mean I could only kill Christian cows?”

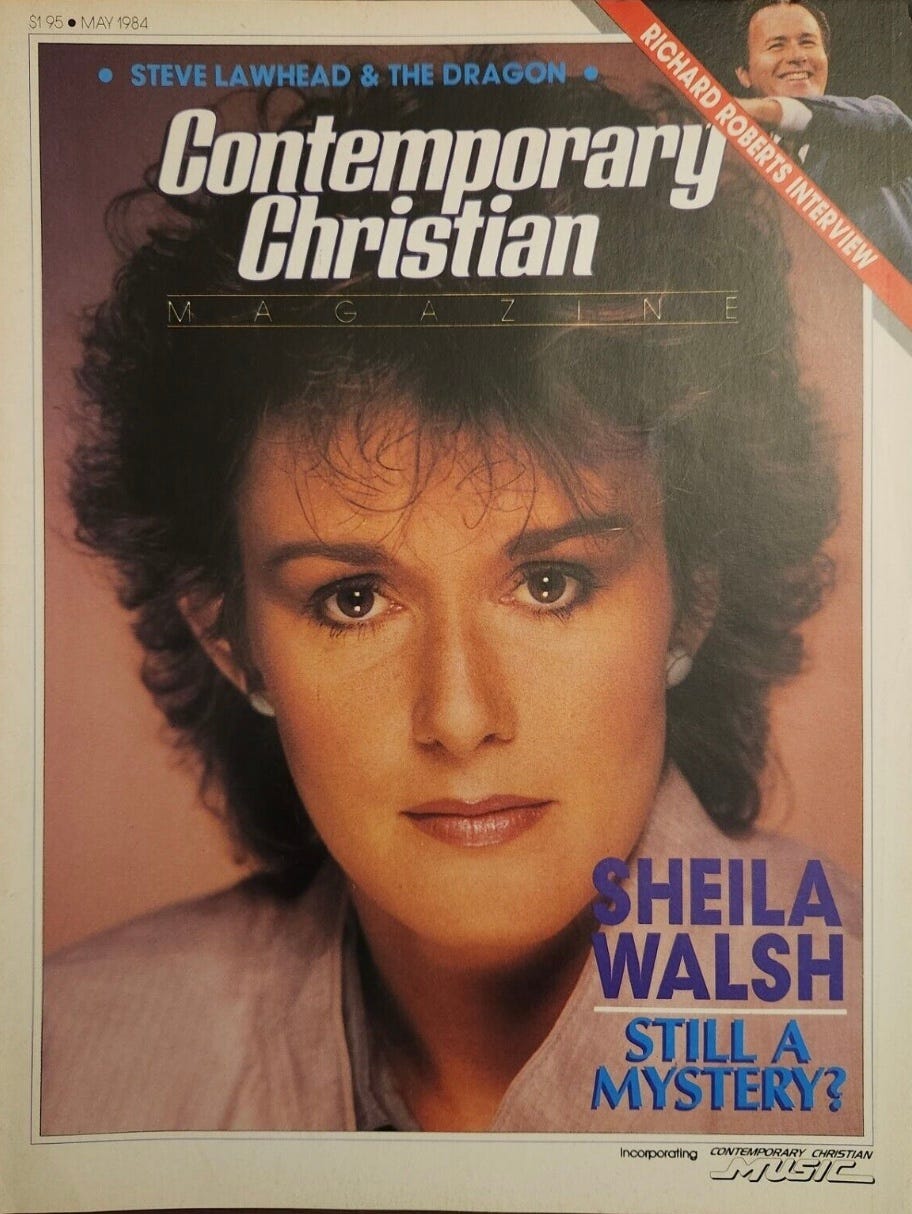

Listening to the album’s most directly Christian tune, “God Put a Fighter In Me,” in 2023 might take more progressive listeners aback. It could certainly be–and certainly was—heard as an anthem of Christian nationalist rhetoric by American CCM listeners. But, context is everything. In May of 1984, Sheila was Contemporary Christian Magazine’s cover story and reading her thoughts about America’s brand of Christianity certainly aids the listener in hearing “Fighter” and Walsh’s catalog of the eighties with different ears and more deeply understanding her quest to “re-educate the non-Christian world as to what Christianity is.” She told CCM’s assistant editor Carolyn Burns, “In England, if you asked people if they were Christians, unless they were really on fire, born again, evangelicals, they would say no. Whereas in America, I think you could ask a lot of people if they’re Christian, and they would say yes. There’s a kind of feeling of ‘This is America, it’s a Christian country, and we’re good respectable people.’ I think there’s a social Christianity around here that doesn’t seem to be in England.”

Walsh’s critique of that social Christianity also included a serious examination of the ways capitalistic success had become intertwined with Christianity as well. Burns quotes Walsh as saying:

“I think a lot of American Christians are very well off. There’s a lot of money around. Yet I’ve watched them on television appealing for money for different things, like new platforms, and schools, and universities. While at home a lot of the new churches don’t even have a church building. There’s just no money, and they meet in people’s homes. I personally find the prosperity doctrine hard to handle. I think it’s only in America because of all the money here. If they’re equating it with godliness, then why doesn’t it work in places like Haiti where you’ve got Christians getting up at six o’clock in the morning for a three-hour prayer meeting? Why doesn’t it work in Communist countries where other people are risking their very lives and jobs? Why doesn’t it work for people like that?

Why are they naming and claiming it if it has to do with being closer to God? I know a lot of those persecuted Christians are far closer to God than I have ever been. I find it hard, considering Jesus said that those who are called by My name shall walk in the way which I walked. He also said that the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head. The thing I object to most is the idea that it’s our right. That we have a big Sugar Daddy in the sky, and we keep lifting up our requests. To me that’s not what praying is about. It’s about worshiping God, coming closer to His heart, getting to know Him more.”

What Walsh’s CCM feature revealed was a deeply watching and thinking woman who possessed a particular cross-cultural awareness that many American Christians did not care to understand. “Some people in the Midwest asked me why I don’t use the language of the kingdom more–why I couldn’t talk about being ‘washed in the blood’ and all that. I tried to explain to them that I hoped I could talk in a way that everyone could understand. I explained how I had been to a high school that day and I knew that there were 300 kids from that high school at the concert. I didn’t want to alienate them by using a language that they couldn’t understand. The people finally saw it my way, but they still thought I was too worldly with my language.”

Acceptance in the United States was a challenge for Sheila—and much of that challenge was based on people’s perception of what they imagined her music to sound like based on her appearance on album covers and in stage performances. She was met with a bevy of complaints from Christian audiences in America who were appalled by her attire, short haircut and usage of lights and dry ice on stage. Some, as witnessed by this writer, even called her demonic. “In England, I’m just normal,” she told Cornerstone magazine in early 1983. “Truth is truth,” she explained to a reporter with the Ft. Lauderdale News, “but you can express it in different cultures in different ways.” In a 1985 interview with New Christian Media Quarterly, she expanded on this idea. “Sometimes we think of things being spiritual when really they are cultural. Just because we can’t relate culturally doesn’t mean others can’t….We should never reject people because they look different to us.”

Walsh’s cultural comprehension landed her a gig as host of the BBC’s visionary Rock Gospel Show in 1984. Not only was the program the first of its kind of British television, but it managed to do what no national American show could by presenting the full spectrum of the gospel music umbrella on one platform. In addition to presenting secular entertainers of faith like Deniece Williams, Donna Summer and Cliff Richard, it put Black gospel performers–typically excluded by programs featuring CCM–like The Clark Sisters, Shirley Caesar and Jessy Dixon front and center alongside CCM icons like Amy Grant, Randy Stonehill and Larry Norman. (See below The Clark Sisters’ appearance on The Rock Gospel Show)

There were hopes that the show would migrate to the United States, but that didn’t happen. In our 2017 interview, Sheila said, “I remember Jim [Murray, the show’s producer] flying over to the States to have discussions with people, but there was no place for the show to land because the Christian record community wanted to make sure that everybody that was on the show would be recognized as a contemporary Christian artist. On The Rock Gospel Show, we would have people who were West End musical stars. They had a faith in Christ but they were out there doing [secular work]. That would not have been acceptable in the Christian rank and contemporary Christian music community. I remember Jim coming back and saying ‘This show doesn’t belong over there.’”

I center War of Love (which earned a Grammy nomination) as Sheila’s most consistent and, perhaps, unadulterated work recorded before the full weight of “making it” in the United States set in, as label executives softened her sound, her look and removed her from the unique lane she’d been carving out for herself. Each subsequent album stripped away the edginess that made her so distinct when her 1982 debut album, Future Eyes, introduced her as “one of a few female gospel artists who successfully portray emotional intensity on vinyl.” She told me, “Honestly, I don’t think I had enough courage in those days to kind of go against the suits, to say ‘I’m sorry, but this is who I am and if you don’t like it that’s fine.’ I definitely felt there was pressure to conform…and all the good arguments were there. ‘Do you want people to hear your music?’ ‘They won’t be able to hear you if they don’t get past what you look like.’ Those were very difficult days for me.”

For as much controversy as her presentation elicited and for as groundbreaking as the music was–emerging two years before Stryper similarly shocked Christian audiences with their stage show and boisterous rock sound–she’s more so recognized today as a Christian television personality and best-selling author than for her groundbreaking work as an artist. This period of her life and career should be more loudly celebrated and acknowledged. As Christian music has become even more homogenized than it was in 1984, listening to these innovative albums and reading Sheila’s pointed critique of the then-burgeoning culture helps us understand how it became what it is today: a shrunken market that cares very little about making an impact outside of its bubble.

She wrote in an op-ed for Cash Box in 1986, “The skeptics are many who will say that the world has no interest [in gospel music]. I will never believe this. I believe that what the world is tired of is insincere religious jargon, the trite ‘come to Jesus’ and life will be a blast! The challenge of the 80s for me is that wherever we find ourselves, in the churches of the south, or the rock platforms of our day, to radiate the beauty and reality of God.”

Those are words that deserve to be re-read, contemplated and taken to heart by artists of today who believe that conformity to the norms of the Christian music world are necessary to gain access to the important platforms and to financial sustainability as creatives. The challenge of the 80s is the challenge of the 2020s. While the gatekeepers of the Christian music world successfully squelched the innovation of countless (especially women) artists of the past, it is possible for this generation to refuse to conform to the theological, political and cultural dictates of the Christian hierarchy, not just the aesthetic ones.

Artists like Nichole Nordeman, Amy Courts and Semler have more recently challenged these strictures, utilizing their music and platforms to paint alternative portraits of what it means to be a person of faith today, seeking to make their faith relevant to those who feel excluded by the Christian industrial complex. This is in line with Sheila Walsh’s legacy as a recording artist. She reflected in our conversation, “I think part of my passion has always been to de-mythicize the platform. You know, we assume once the lights hit, everything’s great, that the reason you’re on that platform is because you have your act together. The sad truth is if you as an artist buy into that then the first time you hit trouble, what are you going to do? Where are you going to go? You either fall apart or you start to lie. The spotlight should just be a golden bridge for you to reach out to your audience and say ‘Here’s who I really am and that’s okay.’ I think that’s always been my message. Beneath all the glitz and glamor, I think that’s what women really long for.”

If you want to contribute to the work that is happening here, I encourage you to either become a paid subscriber or contribute to the GoFundMe that I’ve set up for the New York Community Choir book! I am grateful for your support!

So salutary to have this transatlantic perspective on a strain of American Christianity that has always been there but has become oppressively dominant. What a brilliant artist Sheila is, like all the people you write about with the courage to live her/the Gospel deeply and directly.