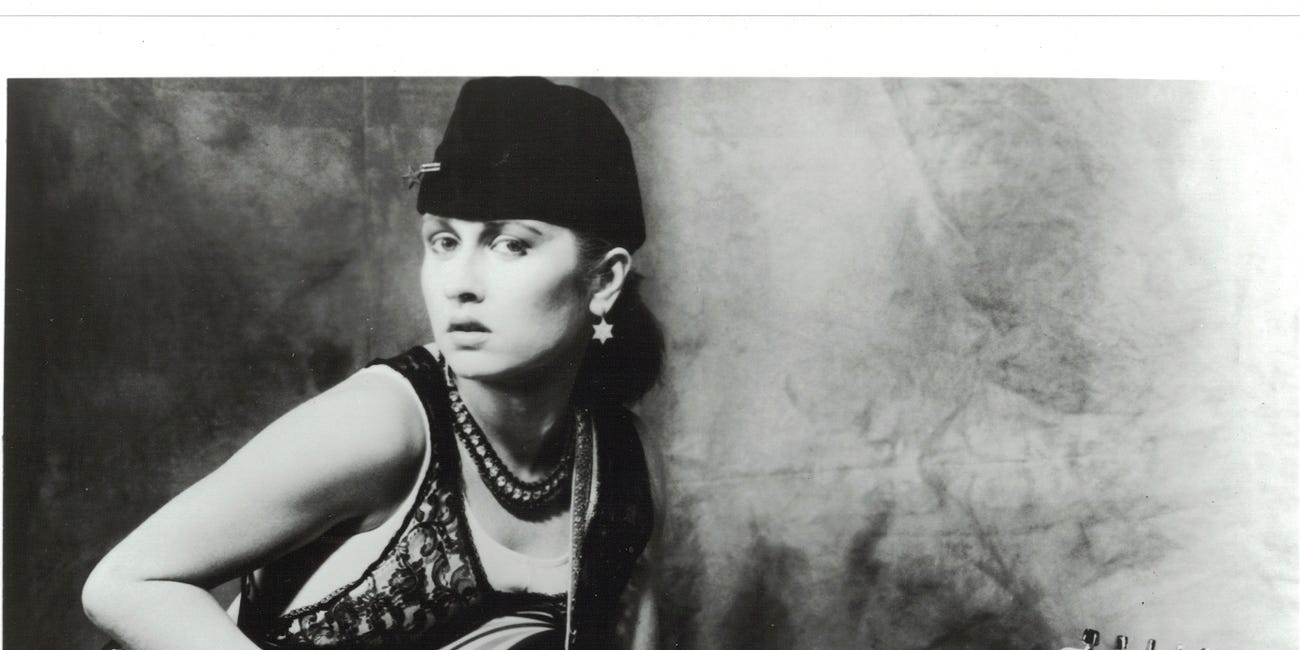

Teena Marie's 'Emerald City'

In honor of the album's 36th anniversary, I take a look at this initially critically-disregarded album.

A big thank you to everyone who contributed last week and helped me hit and exceed the GoFundMe goal! I cannot believe it!! I am so very grateful for your support. I finished chapter 3 last week and am in the first paragraphs of chapter 4 as we speak. The GoFundMe will remain active until 8/23 for any who wish to make a contribution. Now…on to this week’s feature!

Two weeks ago, Teena Marie’s Emerald City turned 36. It’s an album that baffles her more peripheral listeners and is beloved to the deeper ones. Critics, for the most part, hated it. Rolling Stone, for instance, summarized the story of the little girl who wanted to be green, this way: “While it lacks the timeless charm of The Wizard of Oz, it certainly captures all the glitz and vanity of The Wiz.”

The pop success of Emerald City’s predecessor, 1984’s Starchild, may have expanded who heard her music, but it never changed her intention in making the music. As Starchild’s lead single, “Lovergirl,” was beginning to make a dent in the pop charts, she told Billboard, “[My music] is from the streets and that may be unique in the fact that I’m white. I’m happy that I’ve been so accepted by blacks. I could have sung pop long ago and made a lot of money, but that’s not me. My music reflects who and what I am.”1

“Lovergirl” was, in fact, a bit of a fluke in terms of its pop success. The subsequent singles from Starchild did not replicate its chart success on the pop side. If there was pressure to replicate it as she worked on her next album, Emerald City singled a distinct refusal. In fact, it was a burrowing in to her own language, one that crossed Shakespeare and slang with occasional new age references about reincarnation, astrology and astral projection crossed with nods to Stevie Wonder and Donny Hathaway lyrics. Intentionally inaccessible? Perhaps.

Emerald City also ignored musical constrictions. While Starchild had been a focused funk-pop dance record with rock edges offset by some gorgeous ballads, Emerald City brought Prince-inspired programming together with African and Latin rhythms with full blown leaps into hard rock and jazz. There was not a pop single in sight. When asked by a writer at Blues & Soul for the reason behind the music on the album, she replied, “Because it was there.”

She explained to The British Ambassador of Soul, David Nathan, two years later, that Emerald City was “an album I made to please me. People don’t want you to step too far away from what they’re used to. My last album was very different from the work I’d done before.”2

Emerald City is a deep look into the vast terrain of Teena’s musical and spiritual influences. Bootsy Collins, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Branford Marsalis make guest appearances that pepper the album along with the spectacular percussion work of Brian Kilgore. Kilgore and session musician Paulhino da Costa are at the center of the album’s opus, “Batucada Suite,” which articulates the ethos of the album, and more largely, Teena’s art. Kilgore reflected on this in our 2021 interview,

“You read the liner notes and the story she wrote about Pity…and this is the way she [Teena] was…she was so far beyond genres, beyond race, beyond typical human life. She was a citizen of the universe. And that’s what that record was about. Every single song on this record was a different part of the world, a different part of the universe, a universe sometimes of her own making. For me, it was very painful to have that record come out and not receive the acclaim that it deserved because it was so far beyond any genre. She was that kind of artist. She didn’t want to live within any boundary and that album was the ultimate statement of that goal.”

When she returned with 1988’s Naked To The World, she scored her first #1 R&B single with “Ooh La La La,” and remained intent for the remainder of her career on producing commercially viable and radio-ready R&B, scoring just under a dozen more R&B and Urban AC charting singles before her death in 2010.

In 2020, Nick “Nickfresh” Puzo, a DJ and music historian, and I got together to talk about this album in depth and why we love it. You can watch below!

Don’t miss the previous post on Teena’s work and my conversation with author and music journalist Craig Seymour about her!

Cultivating Blackness: A Conversation About Teena Marie

Earlier this month, renowned soul music journalist/historian David Nathan asked me if I’d write an article for SoulMusic.com about my personal experience with the music of Teena Marie. I had no idea how that article would turn my month around and further crystalize my focus on

Ivory, Stephen, “Teena Marie Revives Career,” Billboard, Dec. 8, 1984, pg. 48.

Nathan, David, “Teena Marie Makes a Comeback,” Black Beat, Month unknown, 1988. Web.

Great work Tim!! Her artistry and heart were pure

This is wonderful! Thanks!