The Chance of a Lifetime: Kathy Troccoli's 'Images'

Years before 1991's "Everything Changes" hit the pop charts, this adult contemporary vocalist took her first step towards crossover success with an album about heartbreak, loss & determination.

In the last newsletter of 2022, I wrote about Amy Grant’s recent Kennedy Center Honors acknowledgment and the reasons her revolutionary 1985 album Unguarded was a moment that represented ”the possibility of Contemporary Christian Music escaping the claws of the institution of the church that fitfully claimed it with the intention of re-shaping it into its own image.” Over the next few newsletters, I’ll be focusing on some of the albums that followed in the critical 1985-1986 window that built upon the foundation that Grant and other uncredited crossover constructionists like Táta Vega, the New York Community Choir, Deniece Williams, Cliff Richard and Philip Bailey laid.

By 1985, CCM artists were on the backside of the ecstatic beginnings of the Jesus Movement and finding themselves in religious environments committed to political causes like the Pro-Life Movement and efforts to defund the National Endowment for the Arts. The Evangelical gatekeepers rejected the Jimmy Carter brand of Christianity (which I’d argue was more aligned with the simplicity and innocence of the Jesus Movement) in favor of Jerry Falwell’s dictatorial Moral Majority, whose agenda was wholeheartedly embraced by the sitting president, Ronald Reagan, who had a decade earlier, as governor of California, pledged his allegiance to an agenda of white supremacy, the not-so-silent arbiter of the Religious Right.

While, today, much of CCM [the genre] from the first half of the eighties gets dismissed as wanna-be-pop-fluff that peddled Christian clichés (and, yes, much of that abounded), there were serious singer/songwriters doing their best to nudge their churched-listeners towards inner-thought, challenging them to question or at the very least think about the rigidity of the national Christian perspectives that Christian television and media made real.

Contemporary Christian Magazine (in a short-lived name change from Contemporary Christian Music) was, in many ways, an important tool of (slight) resistance to this agenda. While still largely conservative in its approach, the publication provided a space in which artists could talk about their experiences, concerns, and outlooks, often inciting controversies along the way. In opposition to the hierarchy of the current state of promotion within that world, the magazine placed an emphasis on the artists generating pop/rock that aspired to be viable alongside popular secular music of its time. (Don’t miss Caris Adel’s Substack that evaluates the publication!) They heralded artists like the aforementioned Vega, Williams, Lone Justice, U2, and the Indigo Girls, who were all firmly planted in the mainstream music world, but communicated a particular ethos that spoke to matters of faith. The pages of CCM in “the long eighties” (as Dr. Jafari Allen refers to them) reflect the constant boat balancing that executives and artists were navigating: they could not burn the bridge to the consumers from the church who essentially funded their work but they also could not reach the so-called world without doing just that.

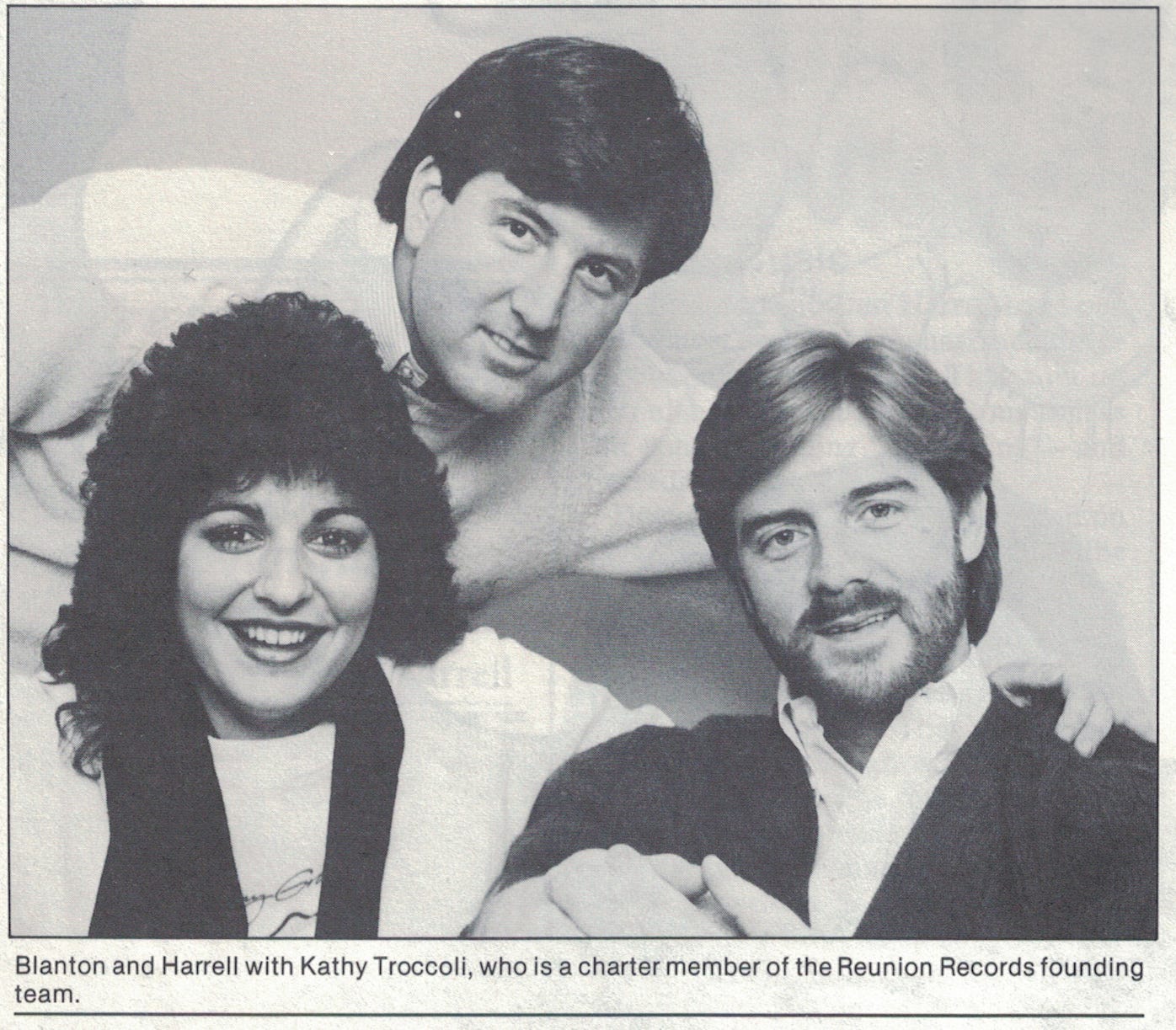

Amy Grant’s management team, Blanton/Harrell, was at the helm of Reunion Records, a label that was founded in 1981 with flagship artists Pam Mark Hall, Kathy Troccoli, and Michael W. Smith. Troccoli had been passed over for label deals, her husky alto off-putting executives more adept at selling worshipful sopranos like Sandi Patty. Troccoli’s vocal tone danced outside of the very specific norms Christian record executives felt compelled to reinforce for their audience. Women were to have high voices (translates feminine), but a certain kind of high (read the criticisms leveled at Reba Rambo for singing the wrong kind of high). Lower voices translated as other things. Sultry is one of the adjectives consistently used in Christian reviews of Troccoli’s work. I’d argue that masculinity is the other signal that lower voices trigger for those kinds of listeners. Make no mistake, these kinds of expectations for women extended beyond Christian music. Women’s music pioneer Holly Near once recalled a label executive telling her that her voice “had no element of submission,” which, the executive claimed, would make marketing her challenging. Kathy told CCM in 1992, “Everybody responded well to my talent but I had a breathy, darker voice and they didn’t know what to do with me.”

But Troccoli scored Reunion a smash hit.

The success of Troccoli’s 1982 debut, Stubborn Love, was largely due to the title track, co-written by Amy Grant, Gary Chapman and Michael W. Smith, which topped CCM’s radio charts. While Stubborn Love was unabashedly and directly Christian, it was evident that Troccoli held promise outside of the genre. “I want to sing to people who don’t normally listen to Christian music. I want them to hear a song in a way that will break their hearts so they’ll be vulnerable to listen to the gospel message,” she told the Kingsport Times-News. The album was a perfectly balanced coalescence of soulful up and mid-tempo tunes, including an oh-so-soulful cover of Ashford & Simpson’s “You’re All I Need To Get By” and heart-wrenching radio-ready ballads like “It’s Your Love” and the aforementioned title track which helped the album sell more than 100,000 units.

Troccoli’s emergence is exceptional, as she was not one of the church’s conventional women. In comparison to the dainty Evie or the model-esque Amy, K.T. (as she’d come to be called) was tomboyish—brandishing little make-up and a Members Only jacket on the cover of Stubborn Love—and self-assured. This was all accounted for in the Christian press with continual reminders that she was from Long Island, New York (italics mine—for emphasis) and was not southern. “There was a lot of ‘softening’ done to me as a woman here [in Nashville],” she told The Tennessean, noting the cultural differences between New York and Tennessee. “I feel like the South has taken off a certain ‘edge.’ I’m a little mellower. I mean, in my family, they scream to pass the butter across the table.”

Early interviews display confidence in her self-knowledge in a room full of men that seem to have been trying to make her more malleable. She told Musicline, “I know my range. I know my voice probably better than anybody does. So I can sink the most meat into it, more than anybody else. I can work around my register. I can work with the best parts of me because I know me better than anybody else.”

Heart & Soul, her Grammy-nominated sophomore effort—released a year before Unguarded—expanded on that notion. It was a little less Melissa Manchester and a bit more Jeffrey Osborne. The album is a tour de force of R&B grooves, powerhouse vocals and well-crafted tunes that sought to make matters of faith of interest to a broader audience than Stubborn Love had. She’s quoted by the Hattiesberg American as saying,

“The sound is not that much different from secular music. It’s geared towards young people. It’s the same sound they’re accustomed to hearing in the Top 40. We wanted them to hear something that’s close to what they hear every day.”

So close, in fact, the Los Angeles Times noted her “R&B/pop crossover potential,” but added, “perhaps too much crossover potential at times—deliberately or not, catchy ditties like ‘Long Distance Letter’…are vague enough to make Jesus sound like a glorified boyfriend.”

She noted the challenges of finding customized material for an R&B-centric project in an interview with Musicline. “Heart & Soul was a little bit frustrating for me because a lot of people weren’t writing R&B and it was like ‘Let’s write these songs for K.T. She wants an ‘All Night Long’ song.’ Michael (W.) Smith comes up with ‘Holy, Holy’ and that kind of thing.” Troccoli’s frustrations speak to the divisions between the Black & white gospel worlds. There were certainly songwriters in 1984 writing the kinds of songs she was hunting for (Bob Bailey, BeBe Winans and Howard McCrary immediately come to mind), but interracial collaborations were still not typical in CCM in the eighties. Troccoli’s own skills as a writer had not been utilized on the album either.

As she toured the album through 1985 opening for Michael W. Smith, she spoke openly about her career aspirations and indicated that her next album would go a step further lyrically and musically. She explained to Musicline, “I’m listening to people like Jeffrey Osborne and Al Jarreau. I like Kenny Loggins, I love Lionel Richie. But, on the other hand, I love Streisand. There’s a part of me that wants to go out on this next album and do a Chaka Khan-Tina Turner thing. That’s where I see myself headed. A little touch of the mellow side of Lionel Richie, like a combination of that.” “I have hopes to sing to the world,” she said without pause on 100 Huntley Street while promoting the album.

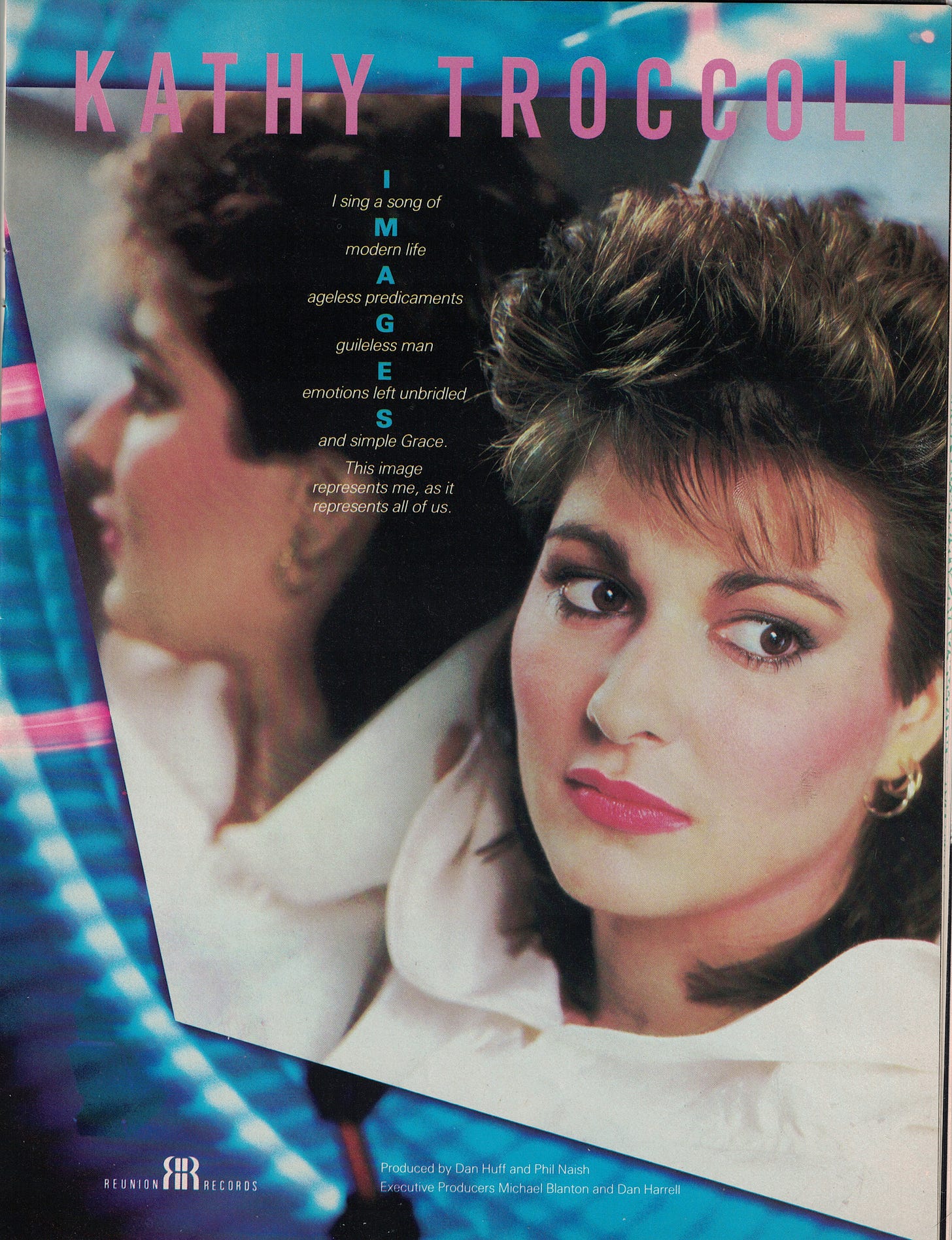

And that’s exactly what she worked to do with co-producers Dann Huff, a in-demand session musician who’d played on albums including Teena Marie’s Starchild and Chaka Khan’s I Feel For You, and Phil Naish. 1986’s Images was a distinct middle-finger to the strictures that the Christian market imposed on its artists. Sonically, the album was leap-years ahead of the conventional fare still popular on Christian radio outlets. In his review of the album for CCM, Mark Eischer notes that the album “hits like a great party record. Sequencers stutter and shake; explosive, violent drums syncopate dangerously off the beat, and untamed guitar solos writhe and snake through dense jungles of reverberation.” Additionally, Troccoli boldly dared to not offer-up a conventional single customized for Christian radio. Not a single song on the album uttered the obligatory God or Jesus-reference, instead opting for an emotionally vulnerable collection of songs about human relationships and their complications, heartbreak and forgiveness, loss and determination.

The album was one of a handful that Reunion Records was utilizing in their desire to reach the general market. Co-owner Mike Blanton told Billboard,

“We’re making a transition from focusing on contemporary Christian music to focusing on artists. We’re finding a few select artists whom we’re convinced enough about their hearts that we don’t mind what they’re singing about. We’re in the business of promoting solid artists as a relating force to the youth of America.”

Troccoli’s Images, Chris Eaton’s stellar Vision and Pam Mark Hall’s Keeper—all released on the Reunion label that year—indicate what could have been for the future of contemporary Christian music post-Unguarded. Whereas Christian music had focused primarily on matters of the spirit, these albums envisioned a more fully embodied life that was not, in Iyanla Vanzant’s words, “neck down dead.” These albums were outside of the propaganda machine that was producing music about abstinence, directing teens to plan for marriage, and the terrors of being pregnant out of wedlock. Images, in particular, directed young people to get to know their hearts, feelings and ambitions.

Reunion’s commitment to these albums, however, was short-lived. Images was ignored by Troccoli’s core audience and did not find an audience in the mainstream—but did earn a Grammy nomination. Billboard’s Bob Darden wrote in his Gospel Lectern column that “there’s nothing bad here. But there’s nothing outstanding, either,” but this writer disagrees. While it certainly deviates from the big production of the stellar Heart & Soul, Images had its own aesthetic that wasn’t interested in recreating the wheel or tickling the ears of those who just wanted the next “Holy, Holy.”

Images plays like a raw nerve exposed, with Troccoli blasting hard-lived songs like “Ready and Willing,” “Chance of a Lifetime” and “Gotta Keep Dancin’” like her life depended on it. That kind of emotional exposure tends to unearth discomfort. Darker themes are always a challenge to sell—particularly to an audience conditioned to anticipate “Jesus made it all better” antidotes.

The biggest difference between Heart & Soul and Images is that Troccoli had finally gotten to speak for herself—she co-wrote seven of the album’s nine songs. She told Contemporary Christian Music that year, “It doesn’t necessarily say ‘Jesus’ here and ‘Jesus’ there, but I feel like I’ve established myself in front of thousands of people and talked about the Lord and His kingdom enough and stood as a Christian woman before audiences enough to know that they can pick up ‘Don’t Wanna See You Down’ and go ‘There’s a Christian heart behind that.’ I don’t feel like I’m compromising at all. If anything, I feel like I’m being more vulnerable.”

Troccoli exited the scene, however, before Images could get off the ground. While the album certainly presented the kinds of pop songs she told the media she’d missed singing, the subject matter of the album reflected the level of emotional tumult she was facing. She later explained to CCM, “I wasn’t content with what I was doing musically and I was getting more and more unhappy because spiritually I wasn’t okay and emotionally I wasn’t okay.”

She moved back to New York and did session work on Taylor Dayne’s blockbuster Tell It To My Heart and Can’t Fight Fate albums, beginning a process of self-discovery and spiritual healing. “Getting out when I did,” she reflected in an early 90’s interview, “helped that process for me of finding out who is it that I am and what is it that I want to sing.” The result of her time away was 1991’s largely self-composed Pure Attraction, produced by Ric Wake whose credits beyond Taylor Dayne included (among others) Mariah Carey, Natalie Cole and Barry Manilow. The album fused the demands of the Christian marketplace with her own desires to sing to a broader audience. The Diane Warren-penned “Everything Changes” peaked at #14 on Billboard’s Hot 100, achieving the long-awaited pop success. Her self-titled follow-up to Pure Attraction produced two more Billboard-charting adult contemporary singles, but found far greater success on the Christian charts with the album’s Dove Award-nominated closer, “My Life Is In Your Hands.”

Since Kathy Troccoli, she has primarily focused her efforts in the Christian market as an artist and personality, writing books, touring the Women of Faith circuit and rolling out her own cruise. Her albums have vacillated between generic Christian cliches with tunes like the aforementioned “My Life Is In Your Hands,” “Go Light Your World,” and the pro-life anthem, “A Baby’s Prayer” (which won her first Dove Awards) and artistic triumphs like 1998’s achingly beautiful and under-appreciated Corner of Eden which undersold her prior albums. She offset her Christian work with exquisite collections of show tunes and adult contemporary classics including Together, recorded in collaboration with Sandi Patty, and 2010’s Heartsongs.

She was one of the first CCM artists to talk about AIDS (albeit in 1997), donating the proceeds from her #1 single “Love One Another” to His Touch Ministries in Houston, Texas, an organization committed to providing support, care and housing for those with HIV/AIDS. When Contemporary Christian Music wrote its first lengthy feature on the AIDS epidemic (also in 1997), Troccoli spoke to the homophobia she’d witnessed in the church—even if she didn’t take an affirming stance. “Since I’ve come to Jesus, I’ve seen probably more of a vehemence toward that sin than any. I’ve been in endless conversations where there are jokes and [gay] people actually imitated. How come they’re not making fun of the adulteress or the teenage pregnant girl? God hasn’t put a specific taboo on this sin—people have. We’re scared of what we do not know.”

Troccoli, like many other Christian artists, was simultaneously aligned with Focus on the Family, a group that has said that the LGBTQ community is made up of people “whose sexuality has been damaged or whose healthy development has been derailed.” She appeared in their Sex, Lies & The Truth video, which promoted their abstinence-only ideology—a counterintuitive approach to AIDS activism. She also, however, co-hosted the controversial, progressive Christian Tony Campolo’s Red Letter Christians series. In 2015, Campolo took the opposite stance of Focus on the Family as it pertained to LGBT people, writing, “As a social scientist, I have concluded that sexual orientation is almost never a choice and I have seen how damaging it can be to try to “cure” someone from being gay. As a Christian, my responsibility is not to condemn or reject gay people, but rather to love and embrace them, and to endeavor to draw them into the fellowship of the Church.”

As the Christian marketplace has become increasingly politicized and homogenized, her difference has become more muted. Glimmers of where she stands occasionally push through. When a 2021 patriotic post for the fourth of July (which was swiftly removed) became a cluster of Facebook users from both political parties asking her for clarity on her positions, she responded to one poster who felt that Biden’s presidency had put the United States “back on track,” by saying “This is too small and too big of a platform for me to get into specifics. With respect, this is not the America I see.”

In October of 1987—six months after the Jim Bakker scandal hit international news—Roland Lundy, Word Records’ former senior Vice President at Word Records during the ‘crossover’ years, told Billboard that the Christian music industry was in a “purging process.” “The strongest facet left right now is the local church. That’s where the numbers are steady—and growing. To that end, the successful companies will work with the local church….That’s where the survivors will have to direct their efforts.”

Lundy’s utilization of survivor is indicative of a traumatic situation. In such a scenario, one does what one has to do to survive, not necessarily what one would prefer to do, which begs the question: how much of what we see in the contemporary Christian market today is a continued act of survival? Was/is the “purging process” not so much a spiritual matter, but rather one that expels individuals who do not conform to the party line? Is the regurgitation of cliché and regressive political values simply for the sake of economic benefit and cultural power? One can only be told what to think, what to say and how to say it for so long before they either develop Stockholm Syndrome or break free from their abusers.

“All your life you’ve been roped and tied/Waiting for your dream come true/Now it’s finally here like a new frontier/Now you’re not so sure it’s for you/Consider the choice you made/You just might be throwing away the chance of lifetime,” Troccoli sang on Images, an album that deserves to be re-evaluated for its resistance and non-conformity. It’s hard to not hear it and retrospectively wonder what might have happened had she and the other artists who were on the edge of the crossover cliff chosen to survive outside of the evangelical bubble.

“…how much of what we see in the contemporary Christian market today is a continued act of survival? Was/is the “purging process” not so much a spiritual matter, but rather one that expels individuals who do not conform to the party line? Is the regurgitation of cliché and regressive political values simply for the sake of economic benefit and cultural power? One can only be told what to think, what to say and how to say it for so long before they either develop Stockholm Syndrome or break free from their abusers.” Great post, Tim. I didn’t listen to Kathy Trocolli much in the 80s because, despite being a victim of church abuse, I was still stuck on the Stockholm Syndrome side of things. Steve Taylor’s music had started to pry me loose in the mid-80s. I wish now I had followed that impulse further and sooner.

I love her voice and I love your discussion of voice, and the way the industry tried to control and define and curtail the power of so many maverick voices, the courage it takes to have a voice.