The Cissy Houston Effect

Paying tribute to this two-time Grammy winning artist whose genre-defying discography spans almost seventy years.

In 2020, I was commissioned to write the liner notes for Let It Be Me: The Atlantic Recordings (1967-1970), a box set collecting the first recordings of The Sweet Inspirations. At the helm of those recordings, of course, was Cissy Houston, whose voice I’d first heard on Aretha Franklin tapes in my youth—I just didn’t know it! But when I saw her on the 1990 Stellar Awards receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award when I was fourteen years old, I was an immediate fan. She made the hair on my arms stand up and I began to seek out everything I could find with her name on it.

She’s the kind of voice people either love or hate—just read the comments on the YouTube videos for proof of that—but the reality is that she’s been at the center of some of the most influential music of the last seventy years…and there’s a reason that artists from so many different genres sought her out to put her stamp on their albums. Give Cissy her flowers!

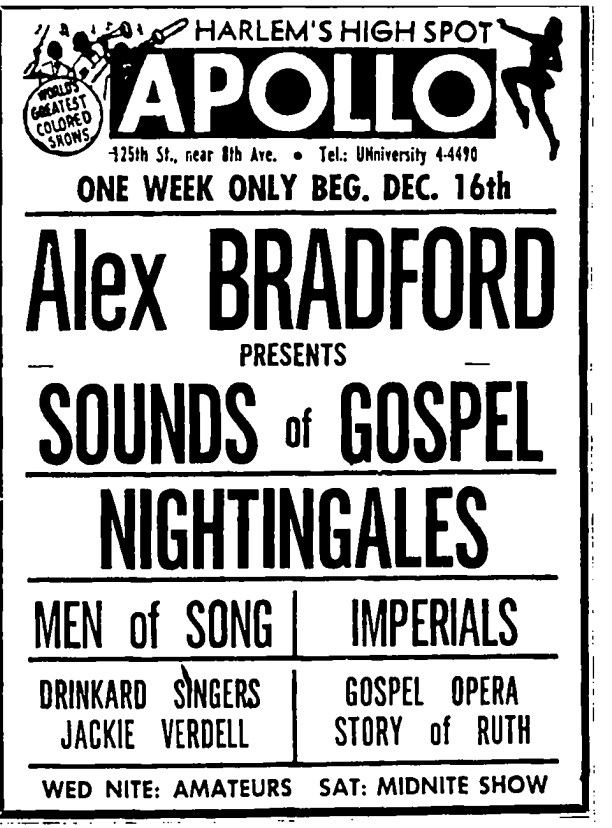

Born Emily Drinkard in 1933 in Newark, New Jersey, Cissy began singing with her sister and two brothers at five years old in the family group,the Drinkard Four. The group would expand when Cissy’s sister Lee (mother of Dionne and Dee Dee Warrick) joined, becoming known as The Drinkard Singers (also sometimes known the Drinkard Jubilaires or the Drinkard Ensemble). After working locally for years and recorded a few sides of Savoy Records in the early 1950s. They were presented at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1957 alongside Mahalia Jackson, Clara Ward & The Ward Singers, Herman Stevens and others, and swiftly signed to RCA Victor where they released A Joyful Noise a year later.

While gospel was providing notoriety, it was not providing a living for the group. The opportunity to do background work for a variety of recording artists presented itself and Cissy happily accepted the work, despite the taboo within the church of singing secular music. It enabled her to quit her job as a factory worker and not just sing, but function as a vocal arranger and contractor at sessions for jazz, blues, soul and pop artists. She cut her first “secular” single as a solo artist in 1963 as Ceciley Blair, daring to not just sing backgrounds on the so-called “devil’s music,” but to step centerstage to sing it.

“I’ve taken a lot of flack from people for singing pop music, but that’s the name of the game and it comes with the territory. I wanted more money to educate my children and to live in a style I had become accustomed to. That’s the only way I could do it. You sure couldn’t do it in gospel music,” she told documentarian Dave Davidson.

By 1967, she was working consistently with Estelle Brown (who she’d brought in from Bishop William Morris O’Neil’s choir at Harlem’s Christian Tabernacle and Calvin White’s Gospel Wonders), Sylvia Shemwell (sister of soul singer Judy Clay, a former Drinkard Singer) and Myrna Smith. Shemwell and Smith were high school friends of Dionne and Dee Dee Warwick who had enlisted the two for their own Gospelaires, the group that opened the door to session work for Cissy.

When Houston, Brown, Shemwell and Smith converged with Aretha Franklin, critics quickly honed in on the fiery energy exchange that would go on to fuel hits like “Chain of Fools,” “Think,” and “Ain’t No Way.” Atlantic executives took “Cissy’s girls,” as they were then called, and signed them to a recording agreement with the label. The late Chuck Jackson is said to have come up with their professional name, “The Sweet Inspirations.”

I chronicle their story in-depth in the liner notes for the aforementioned box set, but will say here that their recordings put Houston’s imagination as a songwriter and interpreter on front street. The Sweets put their own spin on songs that had been hits for others like her niece Dionne Warwick’s “What the World Needs Now” and “Alfie,” restructuring them from accessible pop masterpieces to dramatic gospel operas, filling them with the kind of longing and emotional catharsis that some critics felt was simply “too much.” But that’s exactly what certain listeners loved. In an interview with music journalist Craig Seymour, recording artist Marc Sadane recalled seeing the group perform in his hometown, Savannah, Georgia in his youth, and discovering the gay following they’d amassed that loved “Miss Cissy.”

When The Sweets began a decade-long affiliation with Elvis Presley, Cissy decided to step out on her own. Her first solo album—the self titled Cissy Houston—was released in 1970 on Janus Records and didn’t stray far from the kind of material she’d recorded with The Sweet Inspirations. The album was largely comprised of cover songs and subsequent singles for the label, including the first recorded version of “Midnight Train to Georgia” in 1972, never took off. The song was presented to her as “Midnight Plane to Houston,” but she revealed in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, it was her suggestion to change the title (and chorus of the song) to “midnight train to Georgia,” since her people were originally from the state and did not fly. (Danyel Smith’s book Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women In Pop contains a beautiful homage to Houston—including the “Midnight Train” story—that should not be missed.)

Janus, however, did not promote Houston’s work well and it did not produce the success critics and fans felt she was long overdue. “I just didn’t deal with anything for a time,” she told Rolling Stone in 1978. “I was really disgusted in a lot of ways. I’ve been in this business a long time, and I’m aware of what I can do. I also work very hard at what I do, and seeing people who seemed to start yesterday and are a success today became discouraging. I thought about getting out, and for a time I just devoted myself to my family. But inside, I knew I’d be back again.”

Her time away, however, only pertained to the pursuit of a solo career. While she directed no less than five choirs at New Hope Baptist Church in Newark, she maintained a rigorous schedule of jingle work and recording sessions with everyone from Bette Midler to Van Morrison to Zulema to Linda Ronstadt. Instrumentalist Herbie Mann shared headlining credits with her on his 1976 album Surprises and the same year she was featured in Carmen Moore’s gospel symphony Gospel Fuse.

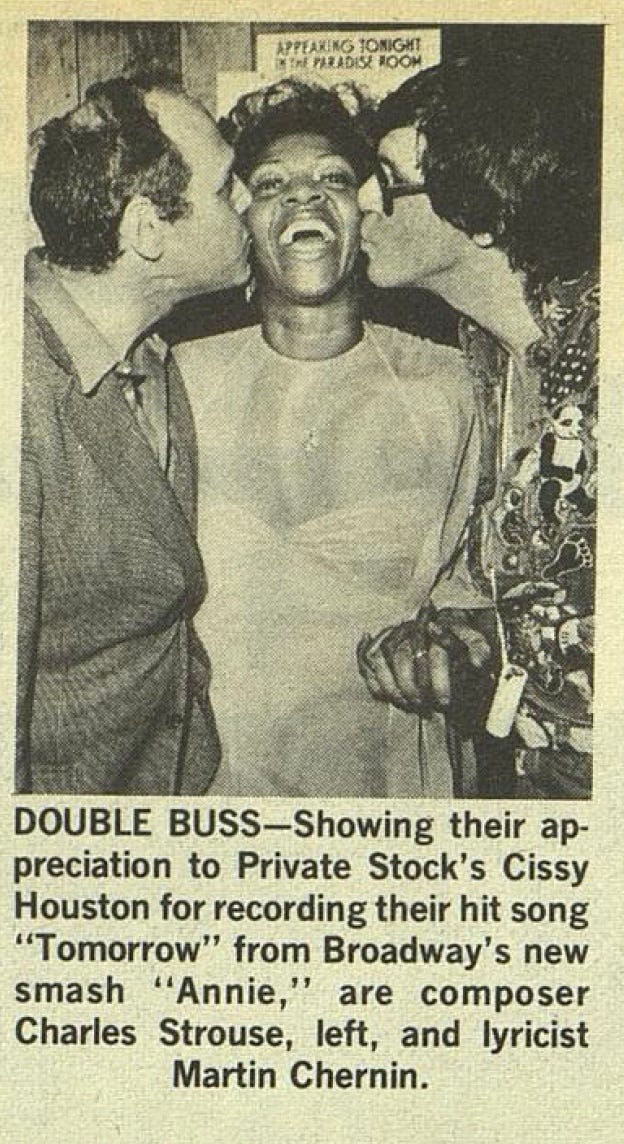

She signed with Private Stock Records in 1977 and released her second self-titled album, composed of originals by producer Michael Zager and his network of songwriters and covers that had become a part of her cabaret act in New York City. Her cover of “Tomorrow” from the musical Annie was the undeniable favorite from her show and the album, with GQ noting how it made audiences “jump to their feet” and Variety predicting that her version “could be a chart buster.”

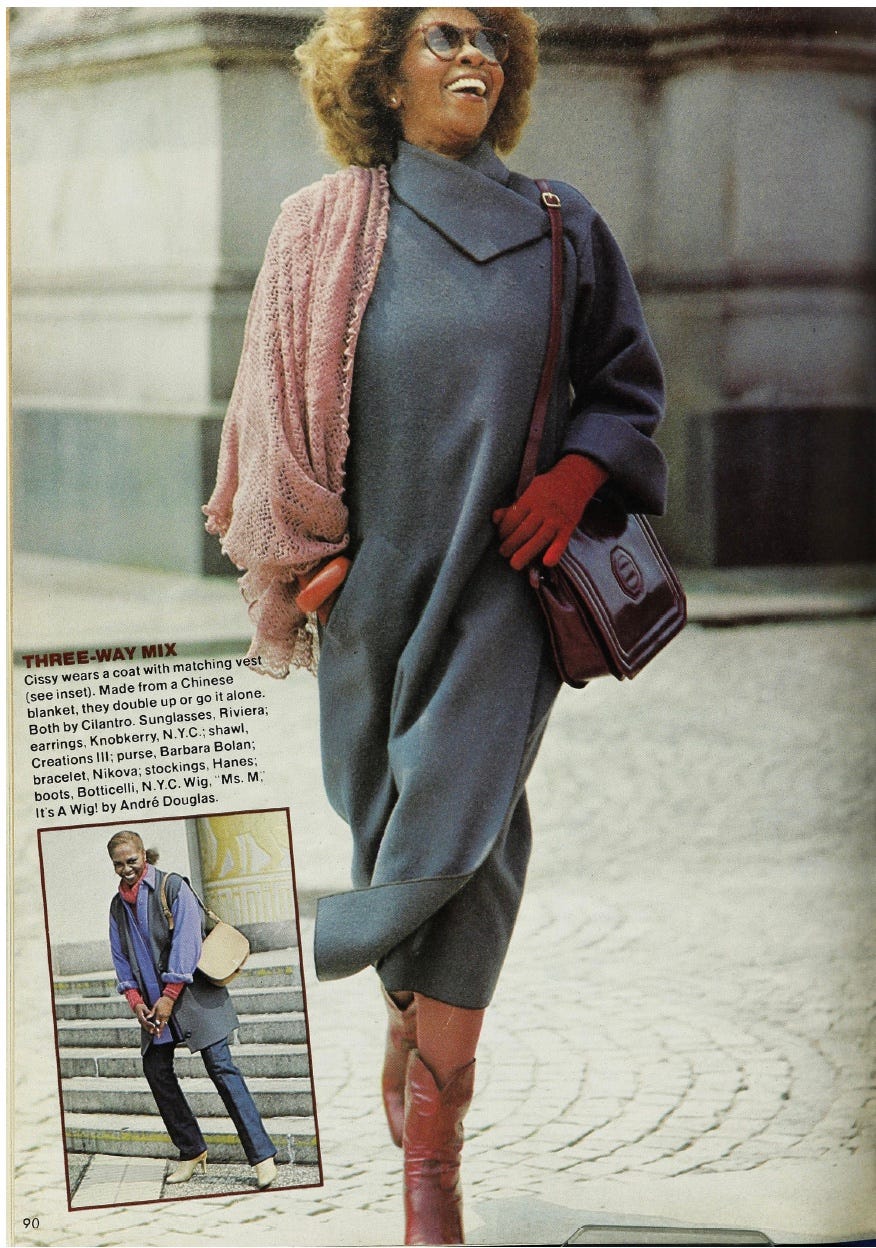

The follow-up, Think It Over, took Houston in a disco direction with the album’s title track and “Warning-Danger” both hitting Billboard’s Disco Action chart. Private Stock succeeded in generating buzz, getting her profiles in Essence and Rolling Stone and rave reviews in Billboard, Variety and the Hollywood Reporter. While she did spot dates in discos to promote the album, her cabaret show continued to reflect her broader musical interests, excluding the disco that was beginning to propel her career forward. Music critic Nelson George wrote that this “suggests that Houston is going in two different directions at the same time. That kind of creative schizophrenia could harm her career in the long run.”

Once again, Houston’s mastery and ability translated as “too much-ness” to an audience that needed her to be accessible and predictable…one thing instead of many things. She told Essence that year,

“You can become quite discouraged in this business. But I took a lot when I first started and I will not let anything crush me. I’ve seen too many people crushed. I had something more than just this business. I had my husband and my three children and they saved me throughout my disappointments. I would not let this business keep me down. Before I do that, I’d leave it.”

1979’s underrated Step Aside for a Lady, once again produced by Michael Zager, was her last solo album for over a decade. The eighties, however, were perhaps even more productive than the sixties had been. Luther Vandross, a Sweet Inspirations fan who she started doing session work with in the seventies, emerged as an artist in his own right. She became, in his own words, “the main character…in my fantasy of how my music is supposed to be,” providing vocal support to his solo albums and productions for other artists. She also appeared off-Broadway in the musical, Taking My Turn, which won the 1984 Outer Critic's Circle Award for Best Lyrics/Music and a Drama Desk nomination for Best Musical.

Her daughter, Whitney, signed with Arista Records as a solo artist in 1983 and Cissy was in the mix, providing unmistakable vocal support on her #1 hit, “How Will I Know” from her debut album, released in 1985. Robin Grace of Nashville’s Twenty-First Century Singers remembers the first time she heard Whitney Houston on the radio, riding with Twenty-First Century contingency Derrick Lee, Everett Drake and Johnny Whittaker. “Johnny was mesmerized because he thought it was Cissy with some kind of effect on her voice!”

With Whitney’s international success in the 80s and 90s, Cissy’s global impact is undeniable. Besides her own body of work as a session singer, a Sweet Inspiration and solo artist that impacted singer’s singers, Whitney Houston has influenced virtually every vocalist that has come behind her. The runs, the operatic leaps and the phrasing that Whitney employed (with the infusion of her own embellishment and influences) were all culled from the model her mother provided her. When we hear those sounds in new generations of singers, we’re hearing the Cissy Houston effect.

“I try to bring feeling to every song I do. I have to feel it before I can make anyone else feel it. Everything I do is real,” she told a reporter for the Los Angeles Sentinel. It’s this drive for realness that makes her sound distinctive. The intention underneath the sound distinguishes it. Some singers simply sell voice...but Cissy's desire was to facilitate an experience. “I’d just like to know that I can command that really big audience. To really give of myself and see the people react—like they do in church. When that happens, it’s hard to hold back the tears. That’s a singer’s reward.”1

God’s Music Is My Life is a free subscription service, but your support is appreciated for this and the expanded work that I do as a historian and preservationist of gospel music history. To contribute, please support the GoFundMe that is helping to make the New York Community Choir book possible.

McEwen, Joe, “Cissy Houston, singer’s singer, steps out,” Rolling Stone, June 29, 1978, pg. 20.

Love love love

This is one of the best pieces you’ve written! Bravo!