1965-1985: Come On Children: The Evolution of Contemporary Gospel

Albums from 1965, 75 & 85 by James Cleveland's Cleveland Singers, the Twenty-First Century Singers and Bobby Jones & New Life that reflect the ways contemporary and traditional sounds trade places.

While gospel music has certainly become a tradition, it’s important to remember that it has always been an evolving, ever-changing form of contemporary music that is two things at the same time: foundational and definitive as an essential part of the fabric of American music, but also a form that reshapes itself utilizing trends in popular music. Thomas Dorsey’s convergence of the blues and spiritual messaging was not immediately a tradition. It was decried by spiritual leaders and remained, in some congregations, a troubling mechanism by which the good news was spread for decades (It’s also safe to say that the dismissal of the gospel sound in favor of ‘worship music’ in contemporary times stems from the same pretensions).

This week’s edition looks at the evolution of gospel music across three decades and the ways in which the most contemporary forms become folded into tradition as time goes on.

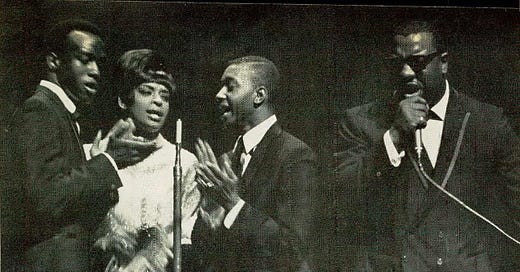

1965—James Cleveland & The Cleveland Singers—He Leadeth Me (Savoy)

It’s easy to forget that James Cleveland’s music—today, considered by many to be the epitome of traditional gospel—was not, by any means, that at all. He was, as Ebony noted in 1968, “setting the whole pace” for the genre. As he moved the genre forward, he did so without drawing the intense criticism artists like Clara Ward or Sister Rosetta Tharpe had before him. He was enough of a preservationist who drew sufficient influence from what had been embraced by mainline churches that it passified traditionalists and masked the ways in which he was progressive.

On the heels of 1963’s genre-changing Peace Be Still with Nutley, New Jersey’s Angelic Choir, Cleveland unleashed the first Cleveland Singers’ album The Sun Will Shine After Awhile in 1964. With Odessa McCastle (alto) and Roger Roberts (soprano) at the core, the personnel vacillated for the first few albums with Charles Barnett and Gene Viale alternately filling the tenor spot, but in 1965, Clyde Brown assumed the role. With Brown, McCastle and Roberts, Cleveland recorded He Leadeth Me.

Each of The Cleveland Singers albums up to this point reflected intense elevation in Cleveland’s songwriting and arranging, brilliantly writing songs that spoke directly to church people, but also had intense resonance outside of the church without reducing his songs to inspirational fodder. He Leadeth Me accomplished that aim once again, but it was also, musically speaking, his most progressive album to date. The punchy “Come on Children” paid as much attention to Ray Charles as Ray Charles was paying to gospel. While it was undoubtedly churchy, it also had a worldly flourish—but not too much of one.

The album’s central tune, “I Don’t Need Nobody Else,” written and recorded by Calvin White and the Gospel Wonders (led by Estelle Brown of The Sweet Inspirations) as “As Long As I’ve Got Jesus,” had a similar wink and nod at the world happening. White’s gospel pop gem was rearranged by Cleveland within months of The Gospel Wonders’ release and became such a hit, only deep gospel lovers realize it wasn’t actually a Cleveland composition. It has become a part of the gospel lexicon, covered by Nashville’s BC&M Mass Choir in the 70s, revived by Vickie Winans on her Live in Detroit release in the 90s, then revived again on TikTok in the last five years. While the song is seen as old school by this generation, it was cutting edge at the time.

The Cleveland Singers sound was equally as compelling as their songs. While male sopranos were certainly nothing new to gospel, Roger Roberts was in a class of his own, bringing an operatic influence that distinguished itself from the male falsettos in the quartets. The emotional unguardedness of Roberts’ soprano was a precursor to singers like Sylvester and Tony Washington of the Dynamic Superiors. Roberts’ voice was not thin, strained or veiled in a butch swagger—it was lush, decadent and decidedly feminine. His was the only voice in the group that could be called pretty. The contrast between Roberts, Brown and Cleveland is evidenced in “That’s What I Like About Jesus,” and it is the differences in their vocal textures that makes this incarnation of the group such a dynamic combination.

In addition to producing gospel standards like “I Don’t Need Nobody Else” and “The Lord is Blessing Me Right Now,” He Leadeth Me also resulted in Cleveland’s own crossover moment. He covered the Vincent Youmans, Billy Rose and Edward Eliscu composition “Without a Song” (from the Broadway musical Great Day), which resulted in a Top 20 Cashbox R&B hit for the group. Cleveland’s arrangement epitomizes the grandeur of the gospel imagination, taking liberties that excavate hidden depths in the song, reimagining melody, rhythm and meaning. It wouldn’t be the last pop song Cleveland would adapt in the gospel field (He would most famously reinvent Gladys Knight’s “You’re The Best Thing That Ever Happened To Me” and a half dozen pop tunes), but it was an early example of his cultivation of this device.

In a moment when choirs were beginning to eclipse the popularity of small groups, Cleveland insisted on advocating for the importance of both. As the years went on, he continued to reshape The Cleveland Singers and produce other groups like the Thornes Trio, The Redmon Specials, Essence, The Troubadors, New Spirit, the Mighty Clouds of Joy and countless others who were negotiating the ever-moving line between the past, present and the future.

Read more about James Cleveland here.

Listen to He Leadeth Me here.

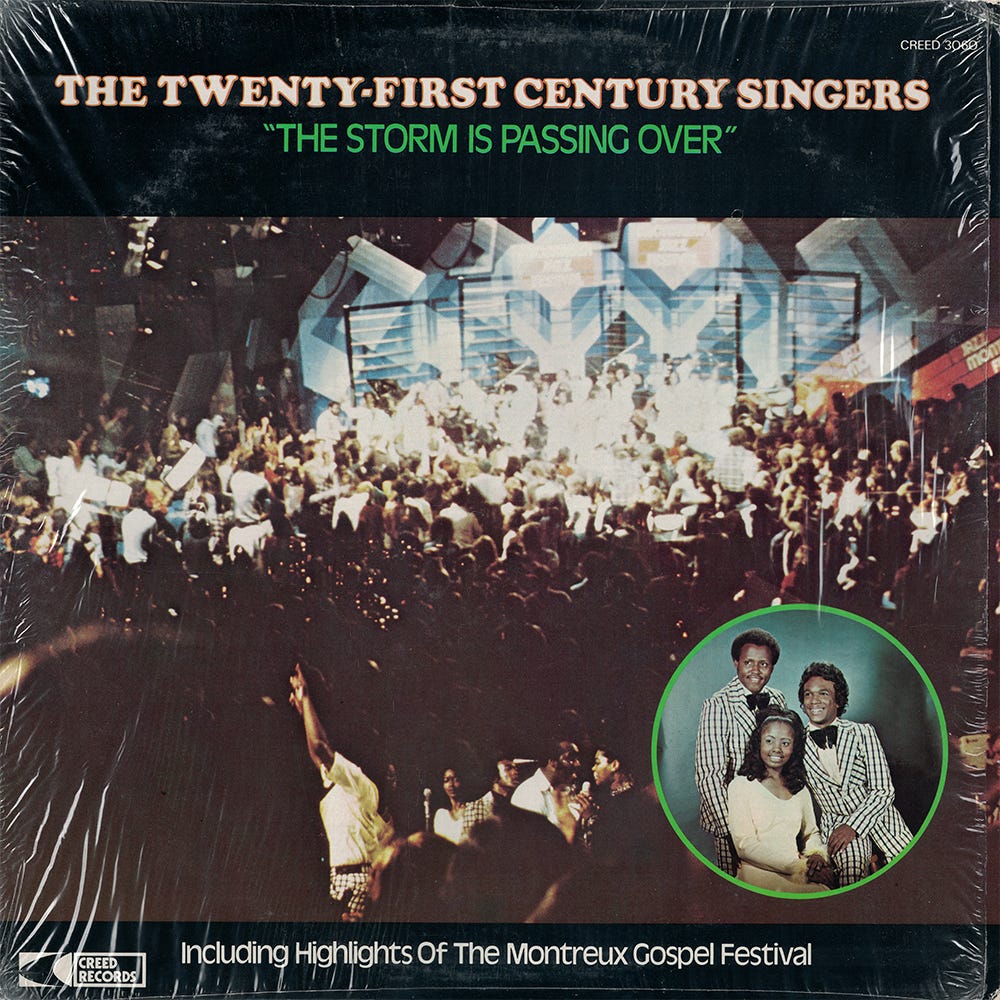

1975—Twenty-First Century Singers—The Storm Is Passing Over (Creed)

Nashville’s relevance to gospel music’s development during the sixties and seventies often gets overshadowed by the contributions of metropolitan cities like New York, Chicago and Detroit which each had a plethora of individualized groups and choirs that achieved popular and commercial acclaim. But Nashville was a consistent presence, notable at the very least as the home of Nashboro Records, a label as prolific in its output as Savoy Records. On Creed Records, Nashboro’s contemporary subidiary, was the Twenty-First Century Singers, a group taking the Cleveland Singers’ ideas a step further. Johnny Whittaker, founder of the group, was a soprano of even grander proportions than Roger Roberts. Whittaker’s sound was grown from Roberts’ influence, but also shaped by Agnes Jackson of the Clara Ward Singers and Cissy Houston of The Drinkard Singers and the Sweet Inspirations.

By 1975, Whittaker had reduced the group from an ensemble of a dozen to a trio, composed of himself, Lula Jordan and Charles Miller. While that year’s The Storm Is Passing Over was the group’s first recording as a trio, they were, by this time, a well-oiled machine whose chemistry and comfortability gave them precision and polish that didn’t sacrifice spontaneity and Spirit Feel. Expanding on their 1973 debut album’s presentation of a sophisticated, orchestrated brand of pop-gospel, The Storm is Passing Over showcases the ways that the Twenty-First Century Singers could navigate in a multiplicty of arenas: churches, concert halls, supper clubs and the emerging world of contemporary Christian music. With one half of the album recorded in the studio and the other live at the Montreux Jazz Festival, listeners are given a snapshot of the full spectrum of what the Twenty-First Century Singers were capable of. Whittaker told the Tennessean after the album’s release, “Audiences respond differently and performers have to be versatile enough to change with their audience.”

The album’s studio side combines gospel standards like “The Storm is Passing Over” and “Blessed Assurance,“ compositions from modern gospel writers like Al Hobbs (“Oh What a Wonderful God”) and Harrison Johnson (“He Saved Me”), and a Broadway tune, “Gonna Build a Mountain” (from the musical Stop the World—I Want to Get Off, recently recorded by Lady Gaga on the soundtrack for the motion picture Joker). Augmented by the Cleveland Singers’ Charles Barnett on piano and orchestral arrangements by Nashville conductor/arranger Jack Williams, the studio recordings elucidate the visionary nature of producer Shannon Williams and the boundless talent this trio possessed.

The album’s live side serves as an homage to their heroes and labelmates The Clara Ward Singers and the Barrett Sisters—they borrow their arrangements of “We’ll Soon Be Done with Troubles and Trials” and “Jesus Loves Me,” respectively, much to the audience’s delight. Miller romps through “Troubles and Trials” with his trademark Baptist growl and showmanship, while Whittaker delivers a virtuosic reading of “Jesus Loves Me,” utilizing much of The Barretts’ version, but Whittaker’s distinction is in the feeling. Even when the notes are the same as the Barretts’, there’s a realness that makes his reading stand on its own two feet.

The group’s performance climaxes with their take on Harrison Johnson’s “I’ve Decided To Make Jesus My Choice,” (replete with one member of the backing ensemble having a full-on country fit) which Miller carries into a sermonette that introduces their rollicking “Swing Down Chariot.” The Twenty-First Century Singers ambition to carry gospel, as Whittaker told the Tennessean, “outside the church circuit,” did not mean that the Spirit, or the music that was becoming considered to be traditional, had to be dampened, minimized, or exterminated. It merely needed to be included as part of a multi-faceted repertoire.

The Storm is Passing Over earned the group their first of two Grammy nominations and the title track gained traction on secular radio stations. Subsequently, the group’s reputation in Nashville grew and their live work increased, appearing on bills with everyone from Waylon Jennings and B.B. King. They made in-roads as one of the few Black groups to be featured at Gospel Music Association events during that era, but they fared better on secular radio than they did on CCM formats. Despite the road blocks, they were one of, if not the, most significant representation(s) of Nashville’s contribution to the gospel sound in the seventies.

Read more about the Twenty-First Century Singers here.

Listen to The Storm Is Passing Over here.

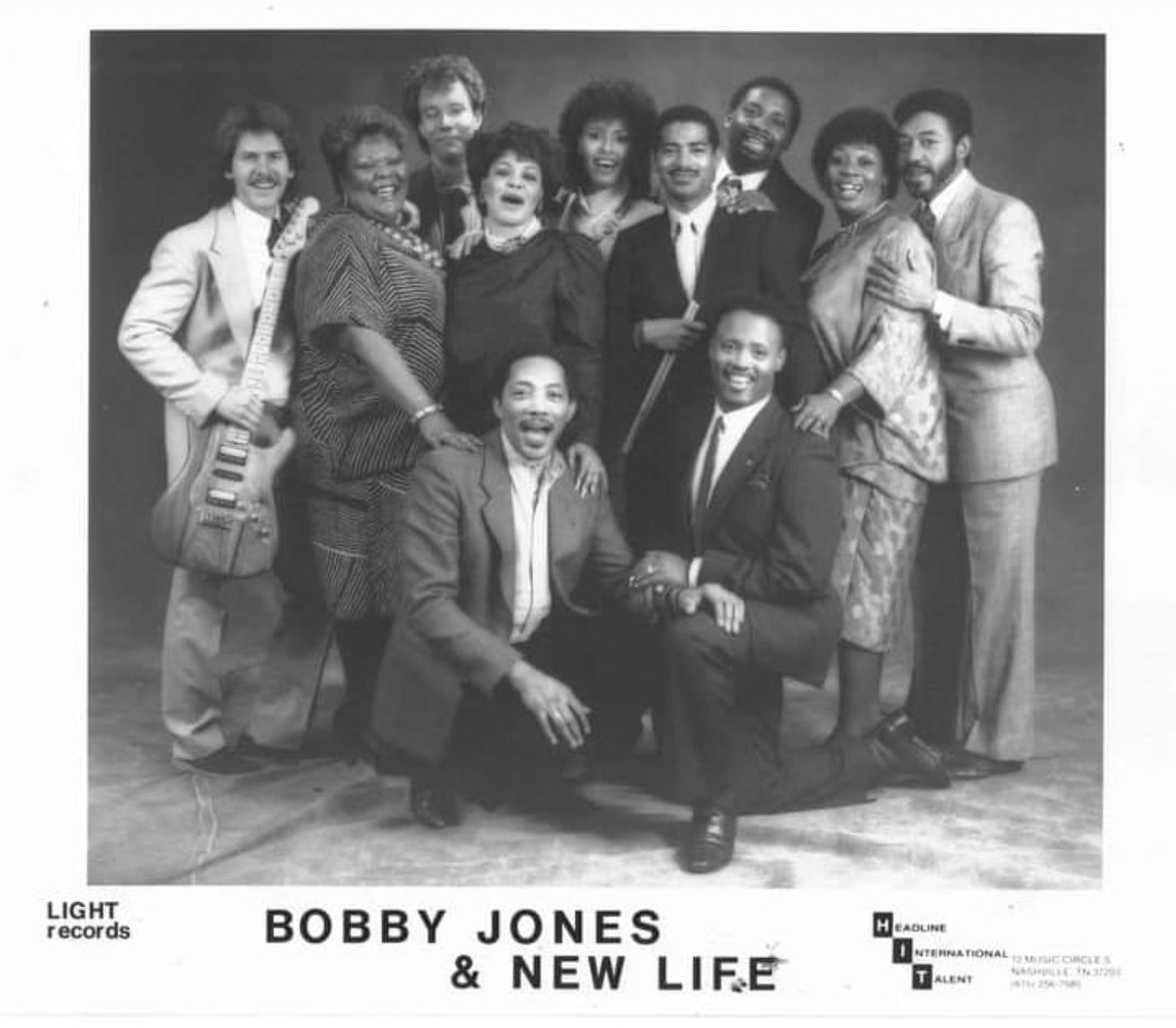

1985—Bobby Jones & New Life—Another Time (1985)

I’ve written a lot about 1985 since the inception of God’s Music is My Life. For certain artists, it was a golden moment. For others, it was transitional.

Bobby Jones and New Life emerged on the national scene in the seventies, in a sense, as a byproduct of Nashville Gospel, the television show on which they were featured that Jones co-hosted with Tommy Lewis and Teresa Hannah. Like the first incarnation of Twenty-First Century Singers, they were initially a large aggregation which united some of Nashville’s best voices (including some original members of the first round of Twenty-First Century Singers).

After three albums that introduced the contributions of musician/songwriter Gerry Jones in particular, Bobby Jones entered the eighties with something new in mind. First, Charles Miller left Twenty-First Century in 1979 and joined New Life. Second, Jones stepped away from Nashville Gospel and began his own television show, Bobby Jones Gospel. Then after hearing the Twenty-First Century Singers’ 1981 release Triumphant, he began a lifelong collaboration with the group’s musical director, Derrick Lee, making him New Life’s musical director. Within two years, he brought Johnny Whittaker and the group’s newest member, Robin Johnson, into New Life, essentially adapting the Twenty-First Century sound as the New Life sound.

Jones and New Life recorded two stellar albums for CCM label, Myrrh Records, under the direction of country super-producer Tony Brown with 1983’s Come Together. That album’s collaboration with Barbara Mandrell, “I’m So Glad I’m Standing Here Today,” earned Jones, Mandrell and New Life a Grammy Award and the ire of some in the gospel music community who did not feel that Jones’ gospel was actually gospel. But like the Twenty-First Century Singers just a decade prior, CCM radio programmers were not adding Jones and New Life to their format despite the group’s polish, accessibility and prime material. When Jones’ agreement with Myrrh ended, he signed with Light Records and determined to make music that served as a bridge back to the Black viewers who watched his television show that might not have necessarily supported his music. He told the Tennessean, “We want to keep those white fans, but this record is designed to attract the Black audience, to get them to buy Bobby Jones. So side one of the album reflects the traditional side of Bobby Jones and the reverse side is a totally different side of Bobby Jones.”

The resultant Another Time was co-produced by Sanchez Harley, Loris Holland and Derrick Lee, who were three of gospel music’s most forefront innovators. Harley had just finished producing Shirley Caesar’s Grammy and Dove winning Sailin’, Holland was working on Tramaine Hawkins’ soon-to-drop crossover opus The Search is Over and Lee was one of the most out-of-the-box writers and arrangers as proven by the Twenty-First Century Singers’ Triumphant and his weekly output cultviating his own contemporary gospel aesthetic with national impact on Bobby Jones Gospel. While Another Time lacked the cohesion of Come Together, it was an album of transition whose vision would be more fully realized on New Life’s last two releases in the decade ahead.

The most impressive element of Another Time is the soloists. The challenge is the material. While Jones’ Myrrh albums were full of strong compositions—much of which came from the pens of Gerry Jones and Bobby Jones himself—the compositions on Another Time suffer from a reliance on catch phrases and cliches that pale in comparison to the kinds of material that Harley and Holland had delivered to the other artists they were working with. It’s the soloists who make the songs work. Emily Harris delivers a blistering vocal on “Stand Up,” supported by New Life’s intricate harmonies and the song’s delightful chord changes. Francine Belcher similarly gives “Jesus I Love You” a depth it would not have had without her. Robin Johnson, one of contemporary gospel’s most unsung soloists, works wonders with the structurally delightful, but lyrically predictable “He’s Coming Again.” New Life itself shines with their one-of-a-kind blend on the lyrically trite “Worship and Adore,” a track that predicts the now-commonplace praise and worship trend. The album’s strongest lyrical moment is (Bobby) Jones’ composition “It’s My Desire,” led by Charles Miller, who never fails to steal the show when given the opportunity to hold a microphone. Jones himself covered Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” in what is perhaps the album’s most musically lukewarm moment. Contemporary Christian Music magazine’s gospel critic Tim A. Smith noted at the time that Dr. Jones’ vocals “are not the strongest.”

No matter the album’s shortcomings, Another Time is important because of its sheer determination to evolve the gospel sound without discarding its roots. The thread that ties these three albums together is just that. Whatever the public has felt about Jones’ contribution as a recording artist, he has been important preserver of gospel music’s tradition and a simultaneous envelope pusher in terms of sound, presentation and message.

Despite changes in technology, song structure and even vocal delivery, these three groups defy categorization as contemporary or traditional—those ideas are subjective based on when they are being listened to and how they are being listened to. As time continues to go on, the threads connecting these artists to today’s gospel music (sadly, increasingly being called ‘worship music’) become less discernable—which is all the more reason we should keep looking back.

Read more about Bobby Jones & New Life here.

Listen to Another Time here.

Collaboration

I’m grateful to have collaborated with Milik Kashad on this piece about the great Loleatta Holloway. If you missed the 5-disc box set I produced and wrote liner notes for last year comprising Loleatta’s Salsoul recordings, you can pick it up from Cherry Red Records here. This week, the project, We’re Getting Stronger: The Gold Mind/Salsoul Recordings 1976-1982, was listed among 2024’s best archival releases by AllMusic.com.

Feeling so lifted after this post! James Cleveland touches me everyt time, and the voice of Roger Roberts was a revelation (hear a little of him in Phillip Bailey.) Also loved Emily Harris on "Stand Up". Thanks always for sharing these gems...

Listening to What do you like about Jesus. I like that question--and the song! The answer right now: I like all the soul-stirring music Jesus inspires. I like that Tim makes sure we can hear it.