4 Albums Turning 40 That You Should Hear

Teena Marie, Leslie Phillips, Andraé Crouch & Sheila Walsh all released blockbusters in 1984. What do these albums have in common?

I had high hopes of being able to write extensive pieces about a dozen or so albums that are celebrating their 40th anniversary this year—but other obligations and the strictures of time are making that impossible. Nonetheless—they are important albums and I want to acknowledge their importance in the ways that I can.

When we talk about the eighties, particularly 1983-1986, we’re talking about one of the most commercially and creatively interesting eras of contemporary Christian and gospel music. The tension between fundamentalism and free expression is most evident in listening to the albums and, at the same time, reading and watching Christian media from the period. I maintain that CCM was at its best in this period because “the church” was still reticent enough about what it perceived as Christian rock that the artists were freer to write and perform in ways that were, intentionally or not, subversive and beautifully dangerous to the religious status quo.

1984 was an important year in that work. CCM had generated a lot of buzz in the music industry as a result of its building sales and marketshare. Many of the artists had expressed interest in taking their careers (some preferred the word ministries) to the next level of commercial success which meant making music that carried a particular approach to life as a person of faith, but may not have been as explicit regarding the particulars of that faith as many of their Christian fans were accustomed to.

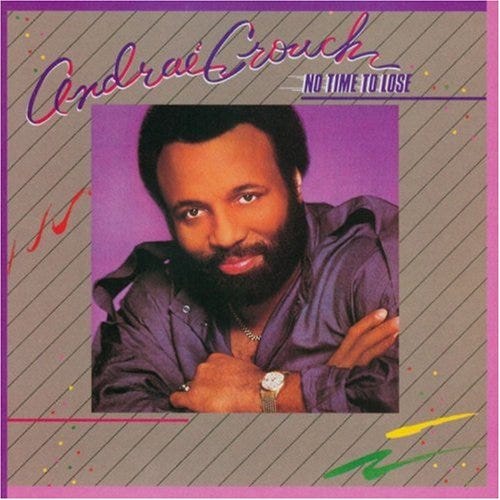

If any artist had been on the forefront of navigating between the Christian world and the mainstream, it was Andraé Crouch. He broke color lines in the late 60s and early 70s with his group The Disciples and then began gaining attention outside of gospel circles with his cutting edge production and polished performances. When he inked a deal with Warner Brothers and released 1981’s Don’t Give Up, an album that colored outside of the lines musically and lyrically, many felt he had gone too far. He tried to make peace with 1982’s staid Finally, but his arrest later that year for possession of cocaine (a charge that was later dropped) only added fuel to the fire.

When he returned with 1984’s No Time To Lose, however, he came back with an album that wasn’t quite as progressive as Don’t Give Up had been (which had included the story of a gay hustler in “Hollywood Scene”), but that wasn’t as timid as Finally. With vocalists Táta Vega (who’d come to Crouch’s camp from Motown), Kristle Murden (for whom Crouch co-produced the stunning 1980 album I Can’t Let Go) and Howard Smith at the fore, No Time to Lose demonstrated Crouch’s ability to write and produce groove-oriented gospel that could create classics for the church (like Vega’s Grammy-nominated lead on “Oh It Is Jesus” and “Always Remember”) and songs that would keep him visible in the mainstream (like “Got Me Some Angels” and “Livin’ This Kind of Life”). The album took him to Saturday Night Live and The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and further expanded his international audience. It was his last release for a decade.

Leslie Phillips was one of CCM’s fast-rising stars. Her 1983 debut, Beyond Saturday Night, produced the Christian radio hit “Heart of Hearts” (written by Mark Heard), but also earned credibility with rock lovers like “He’s Gonna Hear You Cryin’” and “Bring Me Through.” Her sophomore album, Dancing with Danger, kicked things up a notch, incorporating some of the production techniques popularized by Cyndi Lauper’s She’s So Unusual and The Police’s Synchronicity.

While the album’s subject matter (songs warning of the dangers of drinking, smoking and premarital sex, and unrealistic beauty standards in mass media) should have delighted parents concerned about what their children heard on “secular” radio, they were, instead, outraged by Phillips’ dress and performance style. She called the outrage “a lot of rubbish” in an interview with Amherst’s Valley Advocate that year.

Before the year was out, she was being dubbed The Queen of Christian Rock and scoring massive radio hits with the album’s ballads, “Strength of My Life” (on which she was accompanied by Russ Taff) and “By My Spirit” (a pairing with 2nd Chapter of Acts’ Matthew Ward). In 1987, she would decry the albums that preceded her magnum opus, The Turning, as propaganda written under pressure from label executives. (Read more in my feature on Phillips from 2021)

Given Phillips’ feelings about the album, why should it be revisited?

Well, the answer is simple.

While there are formulaic, dogmatic tunes on the album (like the title track and "Here He Comes with My Heart”), there are also some gems. It just depends on how one listens. “I Won’t Let It Come Between Us” could be just as much about succumbing to inauthentic and abusive religious structures and its rewards of church fame and financial reward as it could be about fundamentalist perceptions of sin “in the world.”

Similarly, “Give ‘Em All You’ve Got Tonight” could be less about radical evangelicalism and more about living a thoughtful and consistent life no matter where you are. While peer pressure was certainly a hot topic in 1984, given Phillips’ revelations in the years to come about the intra-communal pressure she was facing, it makes lines like “Hang tight, hang tough, don’t let them sway you,” and “No empty words, no legalistic pride,” stand out as being more about maintaining her own individuality in the church than any pressure she faced outside of Christianity.

SIDE BAR: My 2021 feature on Phillips is the second most-read feature here and the one that consistently draws bitter, misogynistic comments from irrational people (mostly men) who, forty years later, have not accepted Phillips’ departure from fundamentalism and her reinvention as Sam Phillips. I must clarify one piece of misinformation that consistently gets sent my way: Sam Phillips, formerly Leslie Phillips, and Sam Phillips the porn actress ARE NOT THE SAME PERSON. This belief is not rooted in any semblance of truth. A simple google image search of these two different women makes that fact abundantly clear.

So what does Teena Marie have to do with any of this?

Well, I love interconnections. Teena, who emerged in the public’s consciousness in 1979 by way of her 1979 Rick James-produced Motown debut, came to work with Bili Thedford (after his departure from Andraé Crouch & The Disciples) on her 1980 sophomore release on Motown, Lady T, where Thedford provided backing vocals on a few tracks. She then performed on the same bill with Crouch himself the same year at the ShowVote concert in Los Angeles. While her music was decidedly secular (if we must make those distinctions), she displayed a worldview that embraced a variety of spiritual modalities that was not exclusive to Christianity, but always inclusive of it.

But Starchild, the album that took her from the Black Music charts to the pop charts, embraced Christianity in a way that, in this writer’s mind, provided a template for the ways that faith could be referenced and incorporated into pop music without alienating listeners. The album employed two players whose names had also appeared on CCM credits: Paulhino da Costa, a percussionist who had recorded with CCM-adjacent acts like Seawind, Táta Vega and the Mighty Clouds of Joy (as well as Andraé Crouch) and Dann Huff who wove in and out of CCM as a member of White Heart and a session player on 1984’s best-selling CCM albums like Kathy Troccoli’s Heart & Soul, Amy Grant’s Straight Ahead and Phillips’ Dancing with Danger as well the year’s biggest pop albums including Chaka Khan’s I Feel for You, Laura Branigan’s Self Control and Barbra Streisand’s Emotion.

Starchild told a variety of stories of love, heartbreak and rhythm, but “Help Youngblood Get to the Freaky Party” provides imaginative listeners with an idea of what CCM could have sounded like had it not been micro-managed by nervous executives. Abounding with sass and funk, Marie writes the story of leaving church and being met by Youngblood, who propositions her, looking for “a place to lay his head.” Marie responds with Romans 8:13, a scripture warning of the death that comes from living by the flesh. Youngblood responds by telling her “it’s more fun doing wrong.” Marie remains strong, proclaiming “I’m not going to help Youngblood get to the freaky party.”

Marie explained the song to reporter Suzanne McElfresh in a 1985 interview, “There’s a part in the Bible that says to go into the dens of iniquity to preach. The churches don’t need you. It’s the places where the sinners are that need you. At the end of ‘Youngblood,’ the girl goes back to church and the guy goes to the freaky party. I also believe you can’t force things on people. They’ll find it in their own time.”

While the spirituality reflected in Marie’s songwriting reflected elements beyond the bounds of conventional Christianity which certainly would have alienated any kind of CCM audience, it also drew the ire of some critics, including one from Suffolk’s Newsday, who complained of her “vapid lyrics which are in the cosmic Christian vein”—which was exactly part of the Teena Marie magic.

One of 1984’s edgiest artists in CCM was Great Britain’s Sheila Walsh. While today, she’s respected and embraced by the Christian world as an author, speaker and television personality, in the early 80s she was perceived as a dangerous element because of her theatrical performance style (which employed dry ice and dramatic lighting) and her stage attire which did not shy away from spandex, lace and leather. Her music was labelled as new wave, but was, in actuality, a rock-edged form of power pop. Her 1983 album, War of Love, co-produced by Craig Pruess and British pop star Cliff Richard, earned Sheila a Grammy nomination and two hard-earned charting singles on American Christian radio. (Don’t miss my feature from last year on that album)

The British press saw Walsh as more of a light weight compared to some of her secular counterparts while the American church was resistant to what she was bringing. Walsh’s 1984 album, Triumph in the Air, is a study in these contradictions. The rock-edge that had permeated War of Love was gone, but Triumph in the Air’s innovation was in its embrace of electronic drums and synthesizers that moved Sheila in a direction more akin to Sheena Easton and Culture Club.

The album’s most contemporary moments include the ska-influenced “Don’t Turn Your Back on Jesus,” the dance-oriented “Golden Rule,” the Euro-pop of “Somebody” (written by Teri DeSario) and the album’s title track. Offsetting these tracks were a handful of tunes that were geared for American Christian radio like Chris Eaton’s gorgeous ballad “Surrendering” and Graham Kendrick’s “Children of the King,” which might easily have worked for inspirational icon Sandi Patty with a different arrangement.

The dichotomy between the two sounds was also reflected on the album’s front cover. Gone was Sheila’s jet black hair, replaced by a lighter shade of brown. Her clothes were different as well—her look changed by pressure from the record company. Walsh told me in our 2016 interview, “They’ve got me in a white sweater with blue clouds on it [on the cover]. We had such an argument over that photo shoot. I said ‘You brought me over here because I was different…and because this is who I am. But now you want to make me look like everyone else. You want to soften me down.”

But whatever stylistic or visual elements were muted, Triumph in the Air was still groundbreaking in ways that other albums within the genre were not. While it did not earn a Grammy nomination, Billboard columnist Bob Darden called its exclusion “a glaring omission.”

Part Two!

4 More Albums Turning 40 You Should Hear

Last month, I wrote about 4 of my favorite releases from 1984 that celebrate their 40th anniversary this year. When 2024 began, I made a list of albums I hoped to cover extensively. Time isn’t allowing me to do that deep dives that I would ordinarily do, but, again, it’s important to me to acknowledge that these albums happened.

In Case You Missed These…

Reba Rambo's 1980 classic 'Dreamin'' Reissued Digitally!

SONY LEGACY RE-RELEASES REBA RAMBO’S DREAMIN’ FOR 44th ANNIVERSARY In the year that marks its forty-fourth anniversary, Sony Legacy will be releasing Grammy and Dove Award-winning Reba Rambo’s 1980 album Dreamin’ to digital outlets for the first time. Remastered from the original master tapes by Greg Hand, the album will be available for download/stream…

Setting The Intention: Part Four

This past Friday, I was driving home and took a chance and called one of my oldest friends. Joann was the first adult friend I made completely on my own when I was twelve years old or so. She was the music buyer at our local Christian bookstore and one of the first people I developed a friendship without the aid of a church or school connection.

Church of the Good Groove--1st Anniversary Edition

A year ago, I began compiling a monthly playlist called Church of the Good Groove for SoulandJazz.com. My tastes are—shall we say—eclectic…and the ways that music from different genres and eras can converge has always been an emphasis of mine. I also tend to prefer the road less travelled—so the “usual suspects” are less likely to appear on my playlists…

Love the connections you dig up--- Dan Huff and Teena Marie is not one I was aware of!

Happy Birthday to these ageless albums and the artists who recorded them. Thank you always to the storyteller and historian who who bring them into our lives.