Believe In Humanity: The Gospel(s) of Millie Jackson and Inez Andrews

Exploring albums turning 50 by two artists who exercised different--but related--methods of truth-telling in their music.

Gospel music and the blues are different sides of the same coin. Both have historically rendered wisdom earned through the experience of living. Lessons of love, life, the body, the spirit and the soul all come through. As much as some would like to argue that the physical and the spiritual are on different plains, both forms of music actually prove otherwise. Both elicit physical and spiritual responses, transporting the listener between dimensions, resonating with a depth that make saint and sinner (if there even is such a divide) say “Amen.”

Fifty years ago, two very different artists made albums that shared a certain kind of common ground. In many ways, Inez Andrews and Millie Jackson couldn’t be more different. Inez Andrews, an Alabama native transported to Chicago, ascended to the national stage by way of her affiliation with Albertina Walker’s Famous Caravans. With The Caravans she wrote songs that spilled over with folk wisdom, like 1958’s warning, “Your enemy cannot harm you, but keep an eye on your good friend.”

Like Edna Gallmon Cooke before her, she was telling stories called “sermonettes” and merging them with songs. She famously told the story of Lazarus’ resurrection against the backdrop of the spiritual, “Mary Don’t You Weep” so effectively, that when Aretha Franklin covered the spiritual on her 1972 album Amazing Grace re-interpreting Andrews’ story, she made sure to credit Andrews arrangement as The Source.

The year of Franklin’s homage, she had an unlikely crossover to the Top 50 of Billboard’s R&B charts with her recording of Doris Akers’ “Lord, Don’t Move My Mountain,” a last minute addition to the album of the same title that would be released in 1973. The album itself marked a turning point for Andrews, her first collaboration with Gene Barge, largely known for his work with artists like Etta James, Bo Diddley and Little Milton. What many didn’t realize was that Barge had been edging gospel music forward with his innovative productions for Chess Records’ gospel artists (especially The Meditation Singers) and Pastor T. L. Barrett and the Youth for Christ Choir (whose work has only begun to be acknowledged in the last decade). With Andrews, Barge built on her penchant for storytelling.

On their first effort, “Wandering Child” features Andrews rendering a lengthy monologue to parents regarding their children. The monologue was a device healthily employed consistently in soul music as an introduction to a song, but earlier that year by Atlantic recording artist Tami Lynn took it to another level on her quintessential Love is Here and Now You’re Gone. Barge elevated Andrews’ compositions, surrounding her with a sound that was both cinematic and gritty, sophisticated but still soulful.

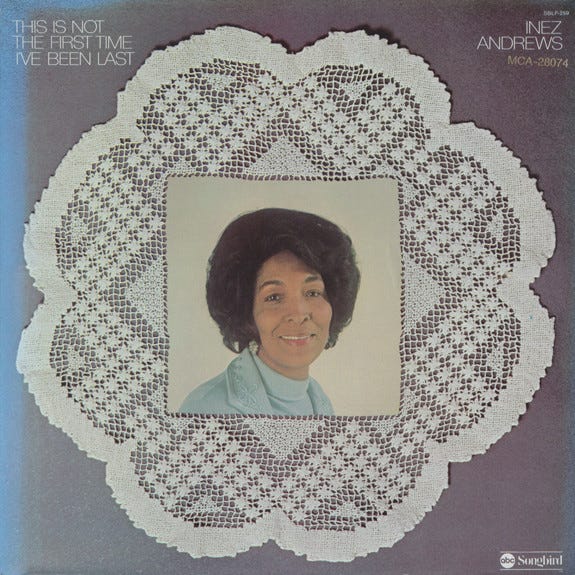

1974’s More Church in the Home (like it’s predecessor, largely penned by Andrews) gave greater insight into Andrews’ societal, spiritual and political concerns. She was a truth teller, concerned by the things she observed in the church and the world. 1975’s This Is Not the First Time I’ve Been Last went even deeper. With a soundscape that sounded like a fusion of Bill Withers and Roberta Flack, Andrews delivered a 9-song manifesto that could just as easily been written in 2025, speaking to conditions that are, sadly, timely and timeless.

One must remember that this album was recorded during the economic recession, a result of an oil crisis, the deficits of the Vietnam War and a series of economic measures exercised by President Richard Nixon that had caused inflation and unemployment. The album’s title track written by Pat White relays this personal and political reality which Andrews renders as a realist, one who is aware, but not surprised. After all, she had survived The Great Depression as a child, worked as a domestic in her youth and experienced the reality of life as a Black woman in Alabama during Jim Crow. She told the Chicago Tribune in 1994, “I have to look at [young] people nowadays when they say ‘That’s not enough money.’ Well, try working six days a week, 10 hours a day for $18 a week, doing washing, ironing, keeping up with the kids.”

But Andrews wasn’t just a realist. She was also a dreamer who envisioned the way things should and could be..and at the center of her vision was faith.

From the title track, she shifts. She nods to the Jesus Movement with “Jesus Power,” a song that invokes a not-in-word-only kind of Christianity, but, rather, one that centers empathy and concern for the practical needs of humanity: food, shelter and resources. From Andrews’ perspective, “Jesus power” means helping others.

In “God’s Humble Servant” (co-written with Barge and Marvin Yancy), she goes a step further to remind those who try to shirk that duty that they are, indeed, simply that. She scolds, “Men of power, I think that it’s time somebody told you….you are God’s humble servant.”

Such a message, however, shouldn’t lead anyone to think that Andrews presumes to have all of the answers. There’s an internal inquiry she pursues throughout the album as well. Covering country/gospel singer-songwriter Larry Gatlin’s “Help Me” (first recorded by Kris Kristofferson then covered by everyone from Elvis Presley to Shirley Caesar), Andrews’ brings the virtual room to a hush with one of the most stunning vocal performances of her career. It should put to shame any who try to reduce the scope of her career to “Mary, Don’t You Weep.” Rolling Stone’s Ken Emerson later wrote of Andrews, “Whether singing with restrained dignity or unreserved abandon, with the serenity of the saved or a raunchy squeal, Inez Andrews is awesome.”

From “Help Me,” the self-inquiry goes deeper with “Lord, Is It Me,” a song that grieves the state of the world, recognizing the places where greed and cruelty abound; but before she finger-points she looks inside to see if there’s a part she plays in it. The three-song suite of prayers culminates with the gospel-blues of “Show Me the Way,” a re-arrangement of a song she wrote and recorded with The Caravans in 1960. It is a prayer not of hopelessness, but of resoluteness to survive and envision a different way of living.

The most obvious influence in regard to her compositional style would be Dorothy Love Coates, who fused practicality and faith with fierce self-assuredness. Andrews didn’t mimic Coates (it’s worth noting that “Show Me the Way” references the winding chain Coates’ references in her own “You Must Be Born Again”), but built upon her template to write music that reflected a way to be “in the world, but of it.” Far from a Christian separatist, Andrews sought common ground with those inside and outside of the bubble of the church. She told the Shreveport Journal, “Religion is not designed to lessen pleasure. It’s purpose is to increase one’s happiness on earth.”

Hence, while Andrews’ vision is certainly faith-based, it’s also humanistic. She has spent a large percentage of the album praying for strength, vision and the ability to enact change by her own actions, but this idea comes front and center in her cover of Carole King’s 1973 composition “Believe in Humanity,” a composition that recognizes the necessity of a higher collective consciousness that impacts how people engage, act and move with one another.

The album culminates with the congregational song, “Shine on Me,” a moment in which she expresses Bernice Johnson Reagon’s articulation of collective “I” in congregational singing, a moment in which the “I” means “we.” From “Shine on Me,” she moves into her own composition “Marching Band,” the album’s final statement which warns listeners to “pray for the nation…pray for the wrong being done by man.”

While This is Not the First Time I’ve Been Last did not achieve the critical acclaim of her two subsequent albums on the ABC/Peacock imprint (the Grammy-nominated War on Sin and the critically acclaimed Chapter Five), it was the most directly political and cultural statement of her career and the most musically ambitious album of her career. Andrews remained clear on the music’s purpose, telling the New York Times in 1979,

“If you've never had an urge to read the Bible, maybe a song will inspire you to. Everybody don't go to church, and some people don't want, to be saved. But when trouble comes, they want to have something they can reach out to. And most times, if it's not the Bible, it's a song'.”

Listen to This Is Not the First Time I’ve Been Last here.

While Inez Andrews was writing and singing about the broader scope of humanity’s political, economic and spiritual state and imagining the possibilities, the Georgia-born Millie Jackson was singing about the realities of life and love on a micro-level.

She left the South for New York at fifteen and after graduating from high school, she began modeling and singing in clubs while working in the clothing district, piecing together a repertoire with the songs of Gladys Knight and the Pips, Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson and the like, cultivating her performance style that was conversational, comical and real. Capturing that on vinyl when she was offered a deal would be the challenge.

Jackson’s 1972 self-titled debut was a somewhat conflicted work. There were sweet, doting love songs like the single “My Man, A Sweet Man” and “You’re The Joy of My Life” which came from the pens of other writers. Years later, she would later sing “My Man, A Sweet Man” rolling her eyes and end it saying “Fine man, sweet man, who gives a ****!” Flowery declarations were not her thing.

Her own compositions on her debut better reflect what she really wanted to talk about. The album’s lead single, 1971’s “A Child of God (It’s Hard To Believe)” (which featured a stunning vocal obligato from Cissy Houston) ruminated about the evangelical embrace of white supremacy subsequently shocking gospel announcers who put it into rotation without listening to it first, unaware that it was not intended to be played in gospel formats (Although, I’d argue to should have been).

She went a step further with 1973’s It Hurts So Good and 1974’s I Got To Try It One Time. Each release built upon its predecessor, kicking up the level of story-telling, reflecting a new actualization of women’s empowerment in song—a woman that didn’t mind telling men what she wanted emotionally, financially and sexually.

She did, however, have to fight for what she wanted to say. She told New York Amsterdam News’ Marie Moore, “There was one song I had to re-write three times because the company thought it was too strong.” The song, she said, was critical of then-President Richard Nixon. “There is a verse in my song that said ‘The President says communism is bad/Democracy there’s nothing finer/but all this seems a bit contradictory/when I see you shaking hands with Red China.’ So I changed the verse to ‘They said all Blacks and Puerto Ricans are on welfare/The white man is paying all the taxes/How can this be if the white man is the only one working and they’re all the bosses/then who’s in the factories?’ They said ‘Well, that is still a little strong.’”

With her second release of 1974, the gold-selling Caught Up, she conceptualized the tale of a mistress on one side and the wife on the other, chronicling the highs and lows of a love affair and marriage. The songs were elongated by Jackson’s monologues, dubbed “raps” at the time, where she began the building of her reputation as a bawdy and brazen woman. The album’s lead single, “If Loving You Is Wrong,” which earned her singular Grammy nomination, was banned by some radio stations, while others bleeped the words “piece,” “little bit” and “funky drawers.”

“Marriages and love affairs are all a part of life,” she explained to reporter Samuel Brooks, Jr.. “That is what people like to hear because it’s closer to home…since it happens to all of us at one time or another. Many artists tell only the positive side of love and the eternal triangle. But that’s not all there is to it. It’s not all peaches and cream, and I’m not afraid to sing about it because it happens.”

She followed the success of the album with its sequel, Still Caught Up, which more deeply traversed the relationship between country and soul, as she further mastered the art of the concept album, once again rendering the perspectives of the wife and mistress. The album’s lead single was Tom Jans’ “Loving Arms,” an enduring composition (once again) first recorded by Kris Kristofferson and Rita Coolidge and covered by everyone from Elvis Presley to the Dixie Chicks. Jackson’s interpretation packed a punch other versions of the song lacked and began a long standing relationship with country music covers. “Lyrically, country music relates very much to rhythm and blues,” she explained to a reporter from the New York Times. “The structure of the song is different, but if you take the twang out of the guitar and put in a fuzz or a wah, it’s basically the same thing. All forms of music are gradually coming together.”

Jackson and co-producer Brad Shapiro didn’t mind deviating from typical song structures to facilitate her unique style. Shapiro been involved with the aforementioned Atlantic album by Tami Lynn which built upon Isaac Hayes’ concept of elongated songs with spoken commentary and Jackson simply did what others might have resisted doing for fear of censors or the respectability police. Groove and story trumped melody in Jackson’s compositions, but Shapiro animated the recordings with elaborate string and horn arrangements, giving the already-story-centric albums the feeling of a film soundtrack. “The Memory of a Wife” and “Tell Her It’s Over” are prime examples. Jackson paints the picture of the story so vividly, it hardly matters that the songs don’t have much melodic movement.

While the influence of Gladys Knight is obvious in Jackson’s vocal style, her overall style is more comparable to Candi Staton’s Fame recordings. This influence reveals itself most in songs like the mid-tempo “Leftovers” (Listen to Staton’s “As Long As He Takes Care of Home” for proof) and ballads like the album’s closer “I Still Love You (You Still Love Me).” While Staton was just a year away from deviating from the southern soul she’d built her secular career upon into disco, Still Caught Up indicated that Jackson was digging her heels in the ground, committing to a sound and a delivery that would earn her a consistent and loyal fan base that didn’t care if they didn’t hear her music on the radio. She told music journalist Steve Ivory after this album’s release,

“If I had to choose between material popular for airplay for what I’m doing now, I’d rather do mine. Richard Pryor has million sellers and he doesn’t get airplay. If you’re doing what people like…it’ll get around by word of mouth.”

Today, some think of Jackson only for the terrible moniker The Queen of Raunch which is an unfortunate reduction for an artist who is a rare example of one who refused to fein virtue in lieu of their own agency and individuality. The trade-off for the freedom to say what she wanted was that Jackson’s own skill as a singer/songwriter was and is ignored. Reputation superseded reality. She explained the dichotomy to Rolling Stone in 1980, “I found out it doesn’t make sense to gear yourself for radio anyway. When I have a clean record, nobody’ll play it. They say it’s not Millie….I’m afraid I’ll be rappin’ as long as Donna Summer’ll be pantin’. But I sell a helluva lot more records than a lot of people who don’t rap so…it’s a trap, but it’s also a very good living.”

Listen to Still Caught Up here.

In Case You Missed These…

1965-1985: Come On Children: The Evolution of Contemporary Gospel

God's Music Is My Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

1985: Where R&B and CCM Meet

God's Music Is My Life is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Love these two women.! We moved on the 1/29 and are in the midst of a plumbing fiasco as I type. Forgive brevity. We survived the move. When we have water that will drain, we might even thrive! Love you storytelling as always.

Loving this . I did keep up with Millie Jackson praying my dad did not catch me due to her language and daddy's baptist roots but hey she had great vocals . Thanks for such great history Tim. Can't wait for more