"Dance, children, dance..."

This choir's gospel of inclusion caused an uproar when they took their message beyond the church and into the discos.

Writer’s Note: Last week, I focused on Amy Grant’s Unguarded (1985), an album that caused a massive controversy in the largely white evangelical world. I’d planned on focusing, this week, on Tramaine Hawkins’ The Search Is Over, released in 1986. I realized, however, that I needed to go a little further back in time to set the stage for that story. Since 2014, I’ve been working on a book about the enormous theological and musical contribution of the New York Community Choir and their roots in the Spiritual Church. I’m sharing, in this feature, some of that work for the first time. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes from Bennie Diggs, Arthur Freeman, Lady Tibba Gamble and Warren Schatz are from interviews that I conducted with them.

If you’d like to contribute to the GoFundMe I’ve created for the NYCC book project, click the button below!

Thomas Dorsey’s invention of gospel in the 1930s was an indicator of the role that this musical form could play in troubling notions of convention, disturbing norms and questioning the Western idea of the sacred and the secular. His brand of gospel blatantly confronted anti-black ideologies which had attempted to excise traditional practices such as the ring shout and the spiritual from the Black worship experience. Dorsey’s gospel-blues countered the attempt of the leadership within the Black Protestant church to, as Michael Harris writes in We’ll Understand It Better By and By, “obliterate indigenous worship music,” which was viewed by church gatekeepers as “an impediment to racial progress.” The resistance to Dorsey’s music was not speculative: he was thrown out of churches and blatantly ignored in others in the early days, but his music broke through during the Depression, an economic and spiritual lift for both the church and its congregants.

As gospel became an accepted form and tradition inside of the institution of the church, innovators like Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Clara Ward & The Famous Ward Singers and Sam Cooke disturbed the peace, raising important discussions about “crossing over,” and followed in Dorsey’s footsteps as they questioned the division of the sacred and the secular. They confronted the dichotomy of restrictions of locations in which gospel could be performed, when the command of the Great Commission was to “go ye into all the world.” Ward and Tharpe challenged notions of respectability and appearance, defied the church’s rigid aesthetic requirements, redefining holiness and humility as internal—not external—qualities, not contingent upon or determined by hair styles, cosmetics, jewelry or elaborate gowns.

At the peak of the Black Power Movement was the crossover success of “Oh Happy Day” by the Edwin Hawkins Singers in 1969, conjuring the same criticisms that Dorsey’s invention of gospel received and the same that had fallen on Tharpe, Ward and Cooke over the course of the prior decade. Hawkins was decried publicly by his contemporaries and foreparents for no other reason than receiving airplay on secular radio stations with his gospel recording. Savoy Records released “Oh What a Day” featuring Rev. Lawrence Roberts, Rev. Charles Banks and Dorothy Norwood which chastised Hawkins for “taking the songs of Zion and displaying them in a strange land.” Despite a loose affiliation with the Peace Movement by way of his collaboration with hippie singer-songwriter Melanie, and his recording of pop songs like “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” and “Blowin’ In the Wind,” Hawkins was largely apolitical, but his imaging and progressive musicality gave him the appearance of difference in comparison with his peers in gospel. Like his predecessors, Ward and Tharpe, Hawkins took gospel to Las Vegas, supper clubs and concert venues with non-gospel artists. A 1969 article in Billboard cited the complications for gospel artists who aspired to mainstream success “because they do not want to alienate their hard-core gospel audience.”

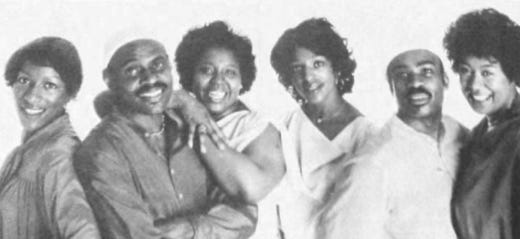

The New York Community Choir emerged in the wake of the “O Happy Day” melee. Co-founded in 1970 by Isaac Douglas, Bennie (sometimes Bernard, sometimes Benny with a y) Diggs, Arthur Freeman and Wilbur Johnson, who had already spent almost five years together touring the country as Isaac Douglas & The Douglas Singers, in response to the challenges of road life. Diggs recalls, “All gospel singers want to get on the road and I have no idea why. It’s a difficult life. I’d never do it again.”

Within a year of their formation, the choir was recording the groundbreaking Truth Is On Its Way with Nikki Giovanni, which placed them smack dab in the middle of the Black Arts Movement. They began touring with Giovanni, while also recording their own albums for Creed Records, the contemporary gospel imprint of Nashville’s Nashboro’s Records. While the majority of the gospel world remained silent in the wake of the Black Power Movement, Diggs says that, for the choir, “it was about being political. It was about being ‘anti’ anything that was status quo. We didn’t want to just be the norm. We wanted to be that which would be in another realm. It was about freedom! Why not join in with freedom?”

Their stance was not met with the approval of the gospel world, however. Citing the lack of engagement between the movement and the church, Bennie says that the collaboration was “where we really got blasted….where we really got knocked in the head.” While the gospel world talked, Diggs says, “Black colleges and organizations would call us in to perform. That was our base. We and the Black colleges kind of motivated that [thought] into the church. It got back to the churches as a result of educated Black young men and women coming out of colleges.”

Diggs, Freeman and Johnson’s ease with what was considered a ‘radical’ message within the mainstream church, however, also had roots. The three had met as teenagers in Harlem’s Christian Tabernacle, pastored by Bishop William Morris O’Neil (he would add an “e” to the end of his name in the 70s). Affectionately called “Pope” by his followers, O’Neil created a space for those considered “outsiders” in mainline Black churches, like his mentor, Chicago’s Clarence Cobbs of the First Church of Deliverance.

As part of the Metropolitan Spiritual Churches of Christ, O’Neil’s Christian Tabernacle exercised a more esoteric brand of Christianity, which Diggs describes as “Christian Scientology.” He says,

“Bishop Cobbs and Bishop O’Neil were kind of on the outside of the church scene. They were where you were not supposed to go. According to other pastors, you were not to listen to that. But I found it intelligent. I thought, ’Well, they’re speaking about life, speaking things into existence. That sounds really amazing to me.’”

The church had a reputation, one that had consequences in certain cases. One former Christian Tabernacle member relayed a story to me of their family destroying the altar they kept in their bedroom, decrying the “witchcraft” they were practicing and ordering them out of the house.

The choir was voted Most Popular Choir in Ebony’s Black Music Poll for three consecutive years, starting in 1974, and continued to tour the black college circuit, both with and without Giovanni. They recorded three albums with the ultra-traditional Savoy Records, but were frustrated with the limitations of Savoy’s technology, years behind what the larger, non-gospel labels had available to them. Diggs, ever the networker, had created, as a by-product of the choir, a group called Revelations Movement (later simply Revelation). Both Revelations Movement and the choir had begun doing session work as backing vocalists for artists like Carly Simon, Melba Moore, The Brothers and others. In 1974, Revelation, sized down to four vocalists: Diggs, Arthur Freeman, Philip Ballou and Arnold McCuller, had landed a deal with RSO Records. Their self-titled first album, released in 1975, produced by Norman Harris, Jerome Gasper and Allan Felder, had placed them in the hands of acclaimed producers in a top-notch studio, with the kind of budget that allowed them to see the full possibilities of their vision.

Revelation was, in truth, a step ahead of what the gospel crossover albums of the 80s and 90s would attempt. Clearly geared for the burgeoning disco scene, Revelation was not down with the hedonistic bent of some of their peers’ work but with songs like “Haven’t Got a Lover To My Name,” “Where It’s Warm” and “You’re Sure To Find Me (Waiting For You),'' they did not shy from the realities of romantic relationships, relaying the desire for and the importance of intimacy and emotional awareness. Their political ideals, which shone brightly in their choir work with Giovanni, were not obscured either. “Get Ready For This” (later covered by gospel artist Gloster Williams and the King James Version), “We’ve Gotta Survive,” and “Just Too Many People” (a Melissa Manchster composition) reflected the concerns over the heart condition of the world. The group opened the Bee Gees’ 1975 20th anniversary tour, which crossed the United States and Canada, often being branded as a “gospel-soul group” in press materials for the tour.

“We would like to be universal and produce a show that includes all kinds of music. We have things to say through our music and we want them to be heard,” Diggs would say to a reporter in 1975. He told Blues & Soul writer David Nathan, “You can tell right away that our roots are still very firmly with the church, but we take a lot of care to make sure that the material we perform really allows us to get our message across in our own particular way. No one is doing what we are doing today and we rely to a large extent on a feeling of freedom on stage, for instance.”

Having had a taste of what was possible with state-of-the-art technology and a budget larger than the $6,000 they typically received from Savoy for production costs, Diggs set his eyes on finding a similar situation for the choir. Warren Schatz, who had been working with Revelation on a variety of ventures for a few years already, had recently been promoted as head of RCA’s Black Music Division. He’d witnessed the choir in session during their Savoy years and knew their potential. “To see the power [in that session] was just overwhelming to me. My life was changed by that experience,” Schatz told me in a 2020 interview. He signed the choir to a deal with RCA and set out to capture the energy of the Savoy session he’d witnessed, but he wanted to pair that energy with top-notch session players and production. His vision was to “produce it as if it were a pop record. The people at RCA thought I was out of my mind,” he says.

Schatz utilized the skills of studio musicians such as Leon Pendarvis, Richard Tee, Will Lee IV and Steve Gadd, and proved that all the choir needed was access to advanced technology and ornamentation to polish what they already had. Diggs added his high school friend, Willard Meeks, who also played with the Long Island-based Benny Cummings & King’s Temple Choir, as a pianist, arranger and songwriter. NYCC co-founder Arthur Freeman emerged as a songwriter on this project, bringing his poetic nature and love of words to collaborations with Sim Wilson and Bennie. It would be one of Arthur’s concepts that would bring the choir unexpected success.

Love, express yourself in me

As I travel through this life

Filled with trouble and strife

Love, express yourself in me

Peace, express yourself in me

When I’m burdened down with care

And it seems there’s no one there

Peace, express yourself in me

Beloved, now we are the sons of God

And it doth not yet appear what we shall be

But we know when He shall appear

We shall be like Him, we shall be like Him

For we shall see Him as He is

Joy, express yourself in me

No more tears in my soul

God has made me whole

Joy, express yourself in me

God, express yourself in me

After all is said and done

And the victory has been won

God, express yourself in me

I’m the beginning and the end

I’m here, there and everywhere

Reach out your hand and I’ll be there

We shall be like Him, we shall be like Him

For we shall see him as he is

Express yourself, express yourself in me

Freeman remembers that “Bennie was reluctant about it. He said, ‘I’ve got to find a melody.’” After some time went by, Arthur checked back in about the song. “He said, ‘Arthur, be patient. I’m still working on a melody.’ Then we were coming home from someplace and he said, ‘I’ve got the melody for “Express Yourself!”’” With a melody composed by Diggs and Meeks, the choir recorded the tune with Linda Price-Webster on lead vocals.

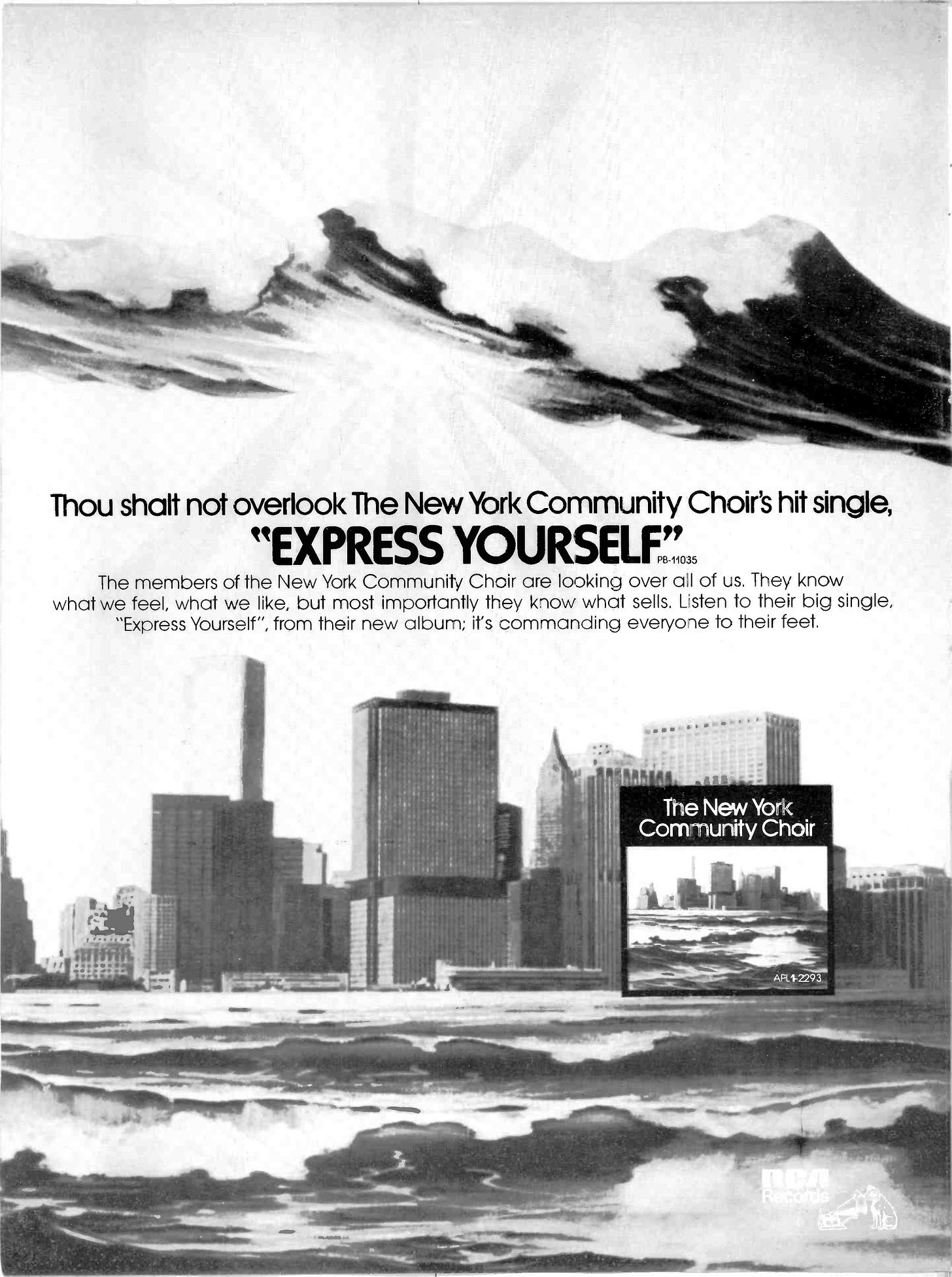

“Express Yourself,” the first single from The New York Community Choir, was an immediate hit, entering Billboard’s National Disco Action Chart in June of 1977 at #20, ultimately peaking at #11. It would chart on the publication’s regional Disco Action charts for Atlanta, Baltimore/Washington D.C., Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit, New Orleans, Philadelphia and Phoenix by the end of the summer. In July, it entered Billboard’s Hot Soul Singles chart at #95, which meant that it was getting radio play in addition to spins in discos. It peaked at #76 and remained on the chart through September.

The success of the single, however, did not come without controversy. Diggs says, “We were almost excommunicated from the churches. It was a big thing. They preached about us in a lot of the churches. [In some churches], we were forbidden! They were forbidden to listen to us. And we had members from [some of those] churches in our group. The bishops used to say ‘Don’t be a part of their group! They’re ‘this’ or they’re ‘that.’ We got called all kinds of names. It was unbelievable.”

The controversy escalated when Diggs and the choir began performing in the discos, contradicting Savoy executive Milton Biggham’s assertion in a Billboard interview regarding gospel’s desire for disco play that gospel artists would “steer clear of personal appearances.” The choir performed at The Loft, a largely gay disco in New York City. Diggs recalls, “We brought the whole choir in. It was an amazing night—watching the whole choir in a disco. We did it knowing [how controversial it was]—but it was fun! These folks would have never heard us [otherwise]. One of our focuses was to get the people that were not in the church so they could hear the word of God. What work are we really doing if we only reach the people in the church?”

Freeman remembered in our 2016 interview, “They [church critics] classified all of us as being gay. A lot of them [church critics] back in those days were stuck in their old ways. We were going to the churches to sing and sometimes they would sit in judgement, you know? But before we left, they’d be dancing and singing.” Lady Tibba Gamble recalled an incident at a New York church service where “Benny and a visiting pastor were going back and forth—we were invited to sing and he was kind of throwing off on our music. When we actually got up [to sing], Benny addressed the issue in his own way.” Interviews with other members of the choir present at that service recalled in detail what was, ultimately, a blatantly homophobic verbal assault on the choir, despite their actual composition of both gay and straight members.

While the intention of the rumors circulated about the choir were hurtful to its members, the rumors themselves were not. Diggs says, “We didn’t have those kinds of negative thoughts about homosexuality.” He continues, “We had a lot of guys that were homosexuals. It was never a problem for any of us. We lived and let live. You were not secluded or segregated because of it. There was enough of that in the world. Why did we need to have it in our community? That’s what I mean about being free.”

The crossover success of “Express Yourself” evoked the same vitriolic, and seemingly incoherent, response as “Oh Happy Day '' had in 1969. One New York choir director, whose church was one of NYCC’s loudest critics, wrote in their own 1977 album’s liner notes, “There is much discussion in the gospel singing world concerning ‘message songs’ as compared to traditional gospel songs. With all due respect to those artists who are so inclined, [we have] only one message and that is Jesus Christ, who is the Savior of all men.” “Express Yourself,” however, was an articulation of that very premise—it was simply set to a contemporary form of gospel and played in venues that did not meet the establishment church’s approval.

The declarative and first person voice of the song is, perhaps, the most outrageous aspect of the song to the fundamentalist listener. “Express Yourself” is not evangelistic in nature—the writer and vocalist are not presuming to be preaching to the listener. Instead, the song is speaking with the listener, as a prayer—which establishes that anyone listening can sing along and speak directly to God, affirming Freeman’s liner notes in which he states that “there must be a divine and universal connection.” Within this universal connection that he writes of, superficial divisions do not exist. All is divine. In “Express Yourself,” God can express Him/Herself through anyone.

The success of “Express Yourself” outside of the church was an affirmation of gospel’s radical possibility. The crossover argument had always centered around artists “watering down” their message, yet “Express Yourself” relayed a blatantly Christian message and was not ambiguous about its spiritual content. It not only crossed over onto secular radio, but achieved success in gay clubs, seemingly the ultimate heresy—the inclusion of and not the preaching at others. Gospel historian Anthony Heilbut writes that “by transporting the church’s joy to the club, the children had given it new life. Just as the gospel world began to turn on its own, the children found a new place to have church.”

Freeman says that “they [those in the discos] felt accepted. They weren’t accepted in the church which I think is atrocious. A lot of them had been hurt by church people and they would just go in, relieved to express themselves. My spirit would leave. The children were jumping and dancing and sweating and I said, ‘dance, children, dance.’”

Jacob Arnold writes in a Red Bull Academy feature of DJ Ron Hardy playing “Express Yourself” in Den One, one of Chicago’s gay discos. He says that “dancers would vogue, back before the term was coined” against the backdrop of “Express Yourself.” Arnold quotes one attendee as saying, “We were standing around breaking and posing and loving ourselves. There was people circling you on the floor looking at these moves that we were doing.” It is this expression that the church could not allow. In “Blackqueer Aesthesis: Sexuality and the Rumor and Gossip of Black Gospel,” Ashon Crawley contemplates the policing of the body and its movements—particularly for men—in the church. “The movement of men—of their body, of their voice—is entirely a feminine, gay, transgressive, transgendered, unholy, ungodly thing,” that, according to the church, “must be forestalled.” It is the possibility of this expression that “Express Yourself” made space for—the I am-ness that transcends human-made norms of gender, sexuality, culture and religion and allows the God-within to become enfleshed.

It is essential to credit New York Community Choir as one of the crucial building blocks that laid the foundation for crossover successes that followed for other CCM and Gospel artists in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Diggs led the choir with ideological clarity from their inception to the end of their run as a unit, which ultimately closed in 1984. They are an irreplaceable part of the story of inclusionist theology and expanded consciousness in gospel music. Their story presents a model for the burgeoning scene of emancipated singers escaping the constraints of the restrictive world of fundamentalism.

To subscribe for the weekly newsletter, click here.

To read last week’s feature, click here.

Come back on Sunday for the weekly #SundayMorningMusic playlist! Listen to this week’s playlist here.